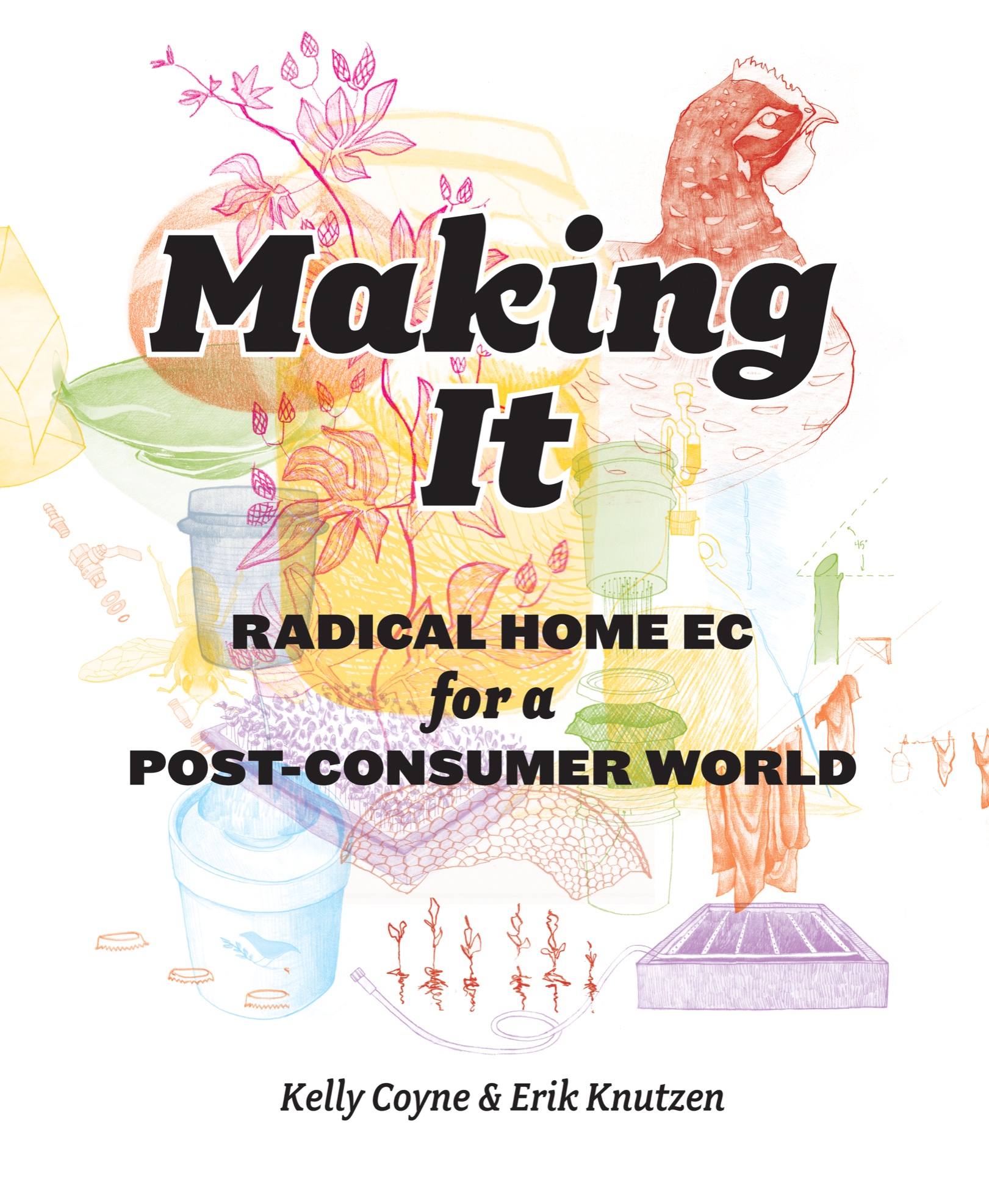

To anyone who is in their kitchen, garden, or garage right now, making it.

Contents

Introduction

Last June, we got a call wed been expecting for weeks. It was from our beekeeping mentor, Kirk Anderson. He said, Ive got a shop vacuum full of 4,000 bugs here for you. Are you ready? We were ready. We wanted to be beekeepers. To do so, wed have to pass through a rite of initiation: transferring the contents of a feral beehive built in a derelict shop vacuum into our waiting hive boxes. It wouldnt be a pretty processbees rarely take well to having their hives chopped to piecesbut this procedure, called a cutout, would not only save the bees from the exterminators wand but also give us a backyard source of raw, organic honey and beeswax. It would be worth a few stings.

Soon after that call, we found ourselves standing in our backyard in sparkling white bee suits, surrounded by an enormous cloud of unhappy bees. Thankfully, Kirk was there with us, wielding a butcher knife like a surgeon, his practiced calm the only thing standing between us and chaos. Both of us were thinking that of all the crazy things weve done, this had to rank right up there among the craziest. And yet wed never felt so alive. Staring into the golden heart of that cracked-open hive was like staring into the fierce, intelligent eye of Nature herself.

The Acquisition of the Bees was one of a string of ongoing adventures that have gradually reshaped and reformed our lives and our home over the past decade. For the most part, our adventures play out in the domestic sphere, in our kitchen and yard. We find fascination in these most ordinary spaces. In the compost heap, our garbage transforms magically into soil. In the garden, seeds sprout and flourish and turn back to seeds. In the kitchen, flour, water, and bacteria mix to make bread. And in the dark recesses of our cabinets, apple juice becomes vinegar and honey becomes wine. Each of these processes raises challenges and questions that lead to more exploration and further adventures.

We didnt start all of this with a particular agenda. The way we live now is the result of a series of actions rising out of seemingly random decisions that, in retrospect, followed a logical path. And that path was dictated by the things we were learning. To turn Zen for a moment, you could say we didnt shape the bread loaf, the bread loaf shaped us. As did the chickens and the bees, the vegetable bed and the worm bin, the laundry line and the homemade soap. Once we discovered the pleasure of making things by hand and the enchantment of living close to the natural world (even though we lived in the heart of Los Angeles), there was no going back to our old ways.

It all started reasonably enough. Twelve years ago, when we lived in an apartment, we decided to grow tomatoes in pots one summer because we were starved for a decent tomato. We didnt know much about tomatoes, but somehow we managed to grow a few. After that first bite of a succulent homegrown tomato, still warm from the sun, our fate was sealed. Wed never buy tomatoes from the store again.

Next we learned to bake bread, and we started to keep herbs in pots. Bit by bit, we began to replace the prepared foods that wed eaten all of our lives with homemade meals. The microwave gathered dust. The impetus behind this slow change was pleasureand a dose of common sense. We figured out that what we could grow or make was inevitably better and usually less expensive than what we could buy. This gave us ample incentive to expand our knowledge base. We moved into a house and planted a vegetable garden. Once we had a little space, things started to snowball.

For the longest time, we didnt understand that our various activitiesbaking, gardening, brewing, etc.were parts of a whole. They were just things we liked to do. Only after we began to blog about our experiments did we form a unified theory of housekeeping. We realized we were practicing old-fashioned home economicsnot the sort of home economics that made for an easy elective in high school, but its original, noble form, in which the household is a self-sustaining engine of production. Instead of buying our necessities prepackaged, we produced them. We disconnected as much as we practicably could from a system of production we didnt agree with and didnt want to support. Our guiding principle is the adage that all change begins at home. The larger forces of politics and industry may be beyond our control, but the cumulative effects of our everyday choices have the power to transform the world.

In time, our blogging led to a book offer. While researching our book, we met people who were remaking their lives in accordance with their ideals. They inspired us and galvanized our resolve. We realized we were part of a wave rising through the culture, a network of backyard revolutionaries who werent content to buy into a green lifestyle based on a slightly tweaked version of consumerism but instead were challenging the foundations of 21st-century consumer culture itself.

We did our best to put what wed learned, and what we believed, on paper. The Urban Homestead was published by the always prescient Process Media in 2008. While The Urban Homestead contained projects, at heart it was a book of ideas. When it came time to write Making It, we knew it had to be a project book, a practical toolbox for transforming ideas into action. We also wanted to show how many of these projects are interdependent and interrelated, how tools and skills from one project apply to and are expanded upon in another, because that is the nature of the home arts. One project calls up the next.

For instance, if youre growing your own vegetables, youll end up with a lot of vegetable scraps and trimmings, which should be composted, because youll need compost to grow more vegetables. Compost becomes vegetables and vegetables become compost. If you want to make your own medicines, you plant herbs. The flowers on the herbs feed honeybees, who make the wax and honey used in homemade medicinewax and honey you can access if you keep a beehive. Interdependent systems are the hallmark of a homegrown household. The economy and elegance in these interconnecting relationships are poetic and, for us, reassuring. The compost heap and the beehive remind us of our place in the world. Were not free agents, floating above it all, but integral parts of the systemus and the chickens and the worms and the nettles and the sunshine.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

One of the questions were asked most frequently is: How do you have time to do all this stuff? The flip answer is that we got rid of our TV . The real answer is much more complicated. But the heart of the question is not how we have time to do this stuff, but how youre going to find time to do this stuff.

The answer is that you do what you can, as you can. When you are passionate about something, the time you need will appear. Beyond that, everything becomes faster and easier with practice. The trick is to learn how to schedule it in and plan ahead. This is a key difference between our accustomed lifestyle of convenience and the home arts. The Quickie Liquor Mart is always open. The home brew needs a month to ferment. The home brew is worth the wait.

Next page