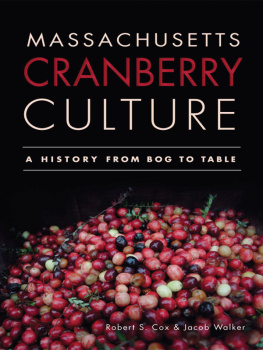

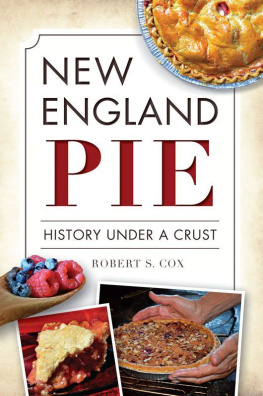

Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2012 by Robert S. Cox and Jacob Walker

All rights reserved

Cover photo by Jacob Walker.

First published 2012

e-book edition 2012

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.61423.676.4

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print ISBN 978.1.60949.513.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Introduction

There are landscapes, and then there are landscapes. There are the juts and crags of the Grand Tetons, arte on arte in a Wyoming row, and the massifs of the Sangre de Cristos of southern Colorado, where dinosaurs nestle in billows of sand. The Great Plains of Nebraska make vanishing points vanish, and in the gypsum crusts of the Great Basin, the spent ashes of a celestial fire still heat the world white hot. There are landscapes on the scale of the imagination.

In such a world of giants, what then of the swamps and snags of Plymouth County and the flat, fetid bogs of Cape Cod? In a world where living awe springs native from the ground, where power and grandeur and the divine apprehension of geological time are fixed in rock and sky, what place is there for the cranberry heartland? Scoped narrow and mean, the land there rolls and rises in modest swells of sand, with barely an awe to be seen. It prefers scrub to forest, hillocks to hills, and the whole slips gently into ocean, not sky. But there is a strange beauty here unlike the Westthe beauty of understatement, the beauty of inclusion. In the West, a visitor looks at land, walks on it or through it, but in the cranberry lands a visitor becomes part of a landscape on a human scale.

This, I think, is the soul of the cranberry.

Cranberry culture is more than the story of turning wild fruit into a cultivated crop; it is the story of how humans have been absorbed into a landscape, how geology, biology, history, agriculture, labor and industry have come together across the years and changed one another through contact. It is an environment of connection, a landscape of the broadest imagination.

Deep Time and Low-Hanging Fruit

William Denton believed that the history of the world could be read in a grain of sand. Literally. Starting with the everyday observation that light reflects off objects onto other objects, Denton theorized that the world could act like a giant all-seeing camera and the Earths surface like a great sheet of photographic film. As events transpired, he argued, light was cast all around, reflecting and refracting, exposing the landscape wherever it came into contact. All that was required, he reasoned, was a suitable method for developing that filmalong with patience, suffering patienceto enable us to witness firsthand every act, every scene and the life of every being that has ever been. Every grain of sand would become a perfect snapshot of the past, the images burned not just on the surface but deep within, only waiting for a suitable application to reveal themselves to the inquiring gaze. How did humans evolve, one might ask, and what killed off the dinosaurs? Pick up a rock, Denton said; develop the image, and the results would be there to be seen as clear as day. How did a trilobite swim or glaciers flow or nations first emerge? The facts were written in stone and held there with astonishing tenacity for all time.

And here was Dentons singular contribution to geological science. Part longhaired poet and serial self-publisher, part radical reformer and Spiritualist, Denton refused to be shackled by the conventions of ordinary chemistry when seeking a method for developing these rocky pictures. Clairvoyance would light the way. With his wife, Elizabeth, and sister, Annie Cridge (both Spiritualist mediums), Denton spent months communing with the natural world, psychically connecting with rocks and stones to reveal a grand history of volcanic eruptions, seismic tremors and upheavals in the lives of countless plants and animals. While other scientists labored to reconstruct the past through painstaking analysis of imperfect remains, Denton witnessed it all firsthand with photographic precision. He had discovered memory made perfect.

Let us admit it up front: the man was eccentric. Few geologists then or now accepted Dentons discoveries at face value, and fewer still adopted his methods. By few, I mean none. Yet as eccentric as he was, Denton got one thing right. Here in New England, in the heartland of cranberry culture and Dentons adopted home, the landscape is self-remembering. The gentle hills of New England, as the saying goes, have fond memories of once being mountains, mountains that were thrust up to Himalayan heights 400 million years ago when North America collided with Africa and Europe. The hills still recall the sublime violence of those events in layer upon layer of twisted rock folded up like ribbon candy, and they commemorate the orogenic consequences in miles-thick sediments shed from the highlands onto mudflats and vast plains where dinosaurs roamed and the flowering plants first evolved and where humans came in colors. The long, straight valley of the Connecticut River is a memorial too, the northernmost of the rift valleys that once gashed the continent from Virginia to Vermont. An aulacogen, geologists call it, where the crust thinned as the continents pulled apart 200 million years ago and where the new continents almost, but never quite, split in two. All it takes is a suitable method to read the land, as Denton might have said, and patience, steady patience.

New England remembers itself in herds of drumlins and eskers, kettles and kames that wander its map and in a landscape sculpted from mountainous remains by years of glacial action. We may not be eyewitnesses to the great North American ice sheet like Denton, but we, too, can read evidence in the land to see tongues of ice flowing far out onto the continental shelf, leaving behind the quirks and coves that spell our shore. Nantucket, Marthas Vineyard and Long Island are little more than heaps of debris bulldozed out at the glacial front, the detritus of dirty ice. Buzzards Bay and the famous flexing arm of Cape Cod are the daughters of a mile-thick sheet of ice carving and plucking and scouring and eroding the rock beneath. The Cape is all hummocks and swales, not peaks and valleys, and everywhere there is sand and marsh and swamp. Since the glaciers at last receded and unburdened New England of their enormous weight, the land has rebounded upward, leaving earthquakes behind to toll in their memory. There are memorials everywhere to our days at the glacial front, from the fossil mastodon that the arch-Puritan Cotton Mather once described as a giant drowned in the Great Flood to the supernumerary rocks that dent our plows and the lonely reptiles and amphibians that call our region home. That New England ekes by with barely fourteen native species of snakes, ten frogs and no lizards at all speaks volumes about how our cold-blooded cousins remember the ice agea hard and shivering timeand hints at how long it takes to slither back home from the South, where they sought refuge and solace.

Next page