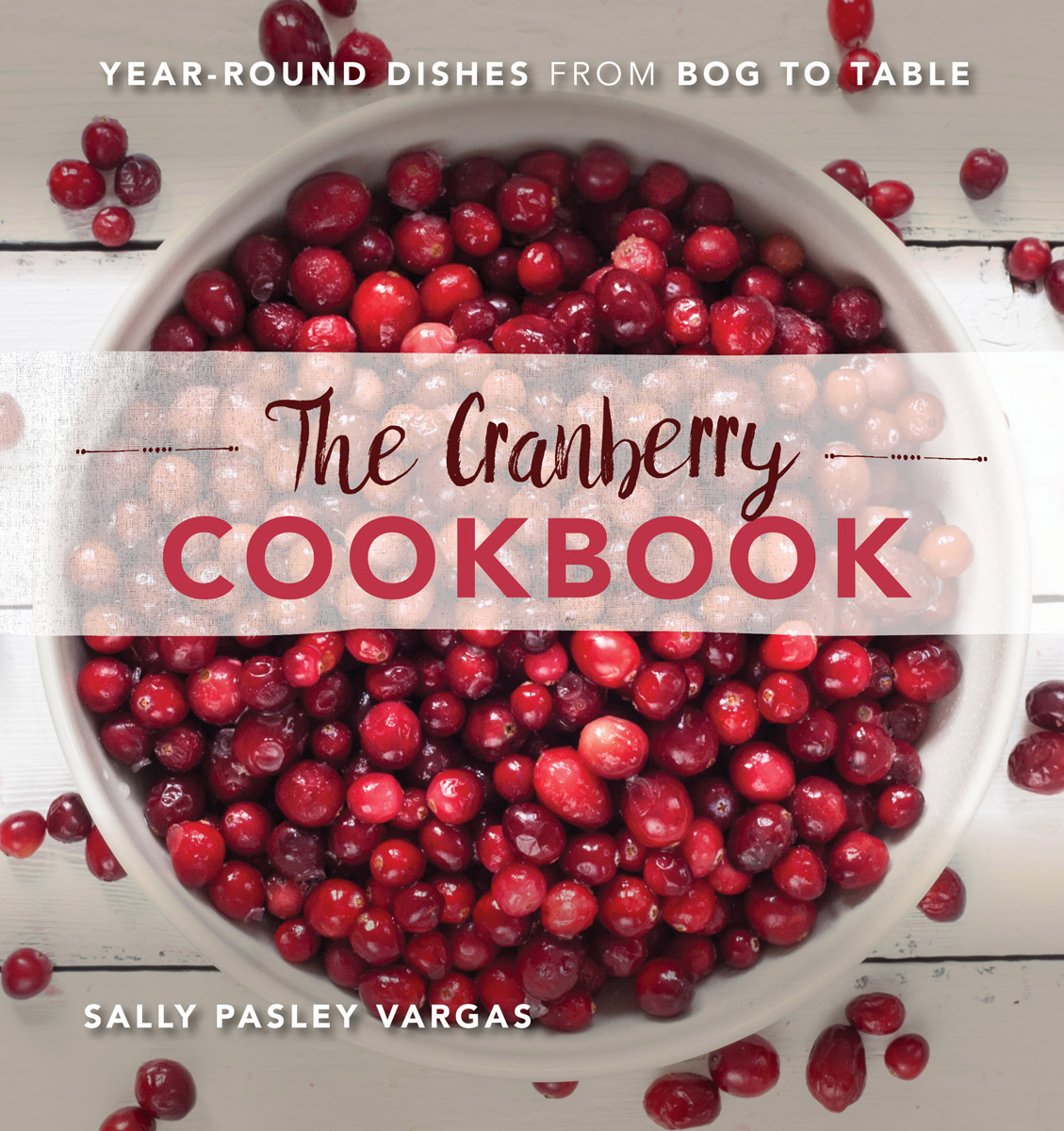

About the Author

SALLY PASLEY VARGAS is a freelance writer and the author of Food for Friends and The Tao of Cooking. She launched her culinary career as a line cook at Rudis Big Indian Restaurant near Woodstock, New York. Her country neighbor at the time, Chef Eugene Bernard, was teaching at The Culinary Institute of America (C.I.A.). He frequently visited the kitchen to advise and mentor the cooks, and eventually arranged for Vargas to intern with pastry chef Albert Kumin at the C.I.A. She is a cooking teacher, coach, recipe developer, and currently writes the column The Confident Cook for the Boston Globe along with seasonal recipes for the Wednesday Food Section. Vargas has written for Vegetarian Times and The Magazine of Yoga. She also contributes to Craving Boston, the WGBH Public Television website. Her interest in photography has led Vargas to combine her love of cooking with photos of beautiful food.

For Luke, who always brings joy to the table

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2017 Sally Pasley Vargas

Photos by Sally Pasley Vargas

(with the exception of those on pages vi, vii, ix, 28, 44, 60, 70, 100 istockphoto.com)

Cover and interior design by Diana Nuhn

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN (hardback) 978-1-4930-2809-2

ISBN (e-book) 978-1-4930-2810-8

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Introduction

On a recent rainy Saturday, I turned off the highway from Boston to Cape Cod to observe a cranberry harvest at a small bog in Freetown, Massachusetts. I left with a bag of gorgeous, fat, red berries and the first thing I did the following day was throw a handful of those scarlet beauties into my morning oatmeal.

Fresh cranberries are wondrous fruits. Tart as can be, they often need sugar to bring out the berry flavor. Because the season coincides with the first big fall holiday, many Americans tend to relegate cranberries to the Thanksgiving table and forget about them for the rest of the year. I hope to change your mind!

A savory roasted chicken with cranberry cornbread salad makes a cozy fall supper, and squash stuffed with berries and wild rice is perfect for the vegetarian table. You could toss a handful of cranberries into roasted carrots, add them to a salad with lentils and feta cheese, mix them with quinoa, or try cauliflower biryani, an Indian dish in which dried cranberries add a piquant element. I cant start my morning without a nutty cranberry breakfast bar when Im racing out the door, and everyones chocolate cravings will be satisfied with chocolate gelato and bourbon-infused cranberries, or a cranberry-chocolate tart. The fresh fruits are often unexpected in confections, and the dried berries can go into any dish that calls for raisinsand maybe Im biased, but I think cranberries are prettier.

In my experience as a pastry chef, chef, cooking teacher, and recipe developer, Ive never cooked with such an adaptable berry. Youll see in these pages of recipes and in my photographs, just how easily they transform sweets with a ping of zesty brightness and how they infuse salads and savory dishes in pleasing and unexpected ways.

When the Colonists came to the New World, they recognized the tart red berries that grew in boggy parts of England and the Netherlands. Native Americans already knew how valuable the fruits were and they found they could sell their harvest for supplies such as flour and molasses, which they did beginning in the nineteenth century. Today, the Wampanoag people on Marthas Vineyard celebrate Cranberry Day on the second Tuesday in October. As Durwood Vanderhoop of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head explains it, We get up early and the cranberry agent opens the wild bog for picking. We say prayers at sunrise, and families gather to pick and share a picnic lunch. Their scoops and rakes have been handed down for generations. Vanderhoop says its the most meaningful of all their harvest celebrations.

Massachusetts, where I live, is one of the leading states in cranberry harvest, and the fruit is the states most important crop. Wisconsin, New Jersey, Oregon, and Washington State are also top cranberry producers. In Massachusetts, many of the growers are in the southeast corner of the state, and sell their crop to a cooperative such as Ocean Spray, established in the early twentieth century. While there have been technological advances in harvesting methods, the growing is still done by small enterprises, oftentimes families.

Surprisingly, this doesnt typically include workers wading knee-deep in water. The fresh cranberries you find in the market represent only a small percentage of the crop and are actually dry-harvested. Until the harvest, trailing cranberry vines grow in low-lying depressions that were originally formed by glaciers. Impermeable clay on the bottom; layers of sandy soil and accumulated organic matter; and proximity to wetlands, streams, and ponds provide the ideal growing conditions for Americas first fruit. The berries thrive in bogs much like wild plants, requiring occasional irrigation if they are being cultivated. The guys knee-deep in cranberries on TV are standing in flooded bogs, a practice adopted in the 1950s to facilitate the harvest. Ninety percent of all cranberries are wet-harvested for juice and dried cranberries.

All fresh or frozen berries used for cooking and baking must be dry-picked, without a trace of moisture. Forty years ago, this meant hand scooping and raking the berries into barrel boxes. When I visited Flax Pond Farms in Carver, Massachusetts, I watched modern dry picking. A dry-harvest machine looks something like a giant lawnmower that combs the berries off the vine and into burlap bags. While the machines have replaced the scoops, it is still a backbreaking job.

Farming is always hard work, regardless, said Dot Angely, who runs the family farm with her husband Jack. In the field, men are bent over, pushing the heavy pickers. Once a bag is full, the berries are dumped by hand into screened boxes to separate the weeds from the fruit. When the picking is complete, a helicopter lifts up stacks of the boxes and delivers them to waiting trucks.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.