An ocean quahog. United States Fish Commission (1872).

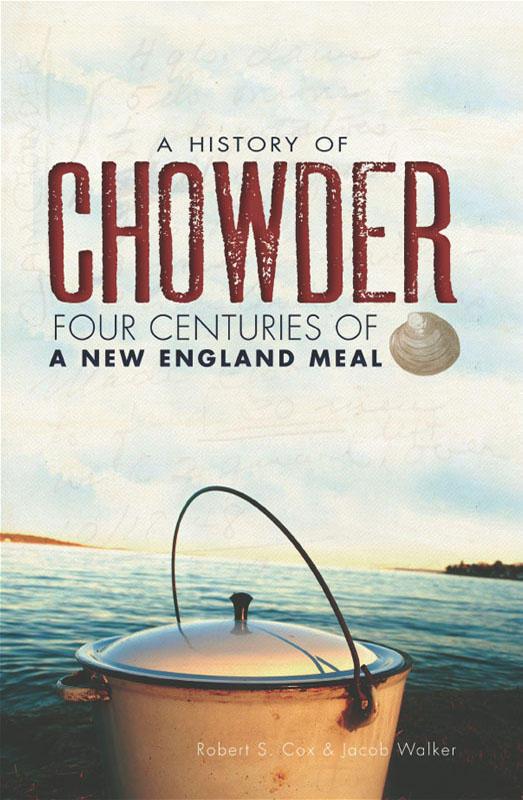

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2011 by Robert S. Cox and Jacob Walker

All rights reserved

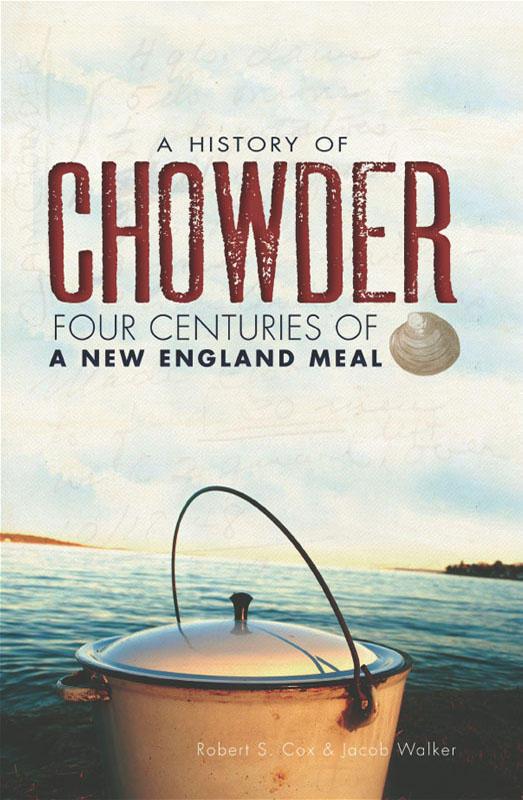

Cover design by Julie Scofield

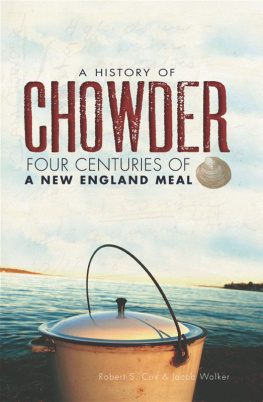

Front cover: Chowder on the marsh. A Woll family pot.

All photographs are by Jacob Walker unless otherwise noted.

First published 2011

e-book edition 2012

ISBN 978.1.61423.350.3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cox, Robert S.

A history of chowder : four centuries of a New England meal / Robert S. Cox and Jacob Walker

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-259-5

1. Stews--New England--History. 2. Soups--New England--History. 3. Cooking (Fish) 4. Cooking (Shellfish) 5. Cooking, American--New England style. I. Cox, Robert S., 1958-II. Title.

TX693.W368 2011

641.5974--dc23

2011017901

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For those who chose the sea

Contents

Prologue

Chowder in Preparation

In the mid-twelfth century in a Benedictine monastery in the Rhine region of Germany, Hildegard of Bingen, a polymath, wrote up a recipe and a cure. It was an ointment for the skin, a treatment for ulcersa mixture of whale brain and water, boiled and mashed with goutweed and oil. It was not her only prescription. Hildegards work on the natural sciences, Physica, contained many: Place the fishs eyelids in wine overnight and drink warm; a paralyzed tongue will come untied. Grind its bones with water and feed it to the pigs; the plague will fade. Her powerful remedies are not meals. They are not testaments to early chowder making found far from the New England shoreline, just reminders of simple importance. The world over, playing with fish, fat and water has long been a part of our humanity.

Time and place may make the creative aspirations of New England cooks more appealing than Bingens (they are), but in essence we are up to the same tricks. Today, the restorative properties of food can be sidelined in favor of celebrations of certain ingredients or exercises in overeating. Chowder, however, carries on its good work. It can be part of the way to live a better life here. If all our references to chowder were to vanish, many might collapse into despair. In 1885, a man in Roxbury, Massachusetts, wrote, Chowder is probably the form of nourishment which most quickly and easily comes to the restoration or refreshment of the brain of man. Maybe he was right.

The progress of chowder eating is different for each of us. For some, the initial taste may be had as a young child, a response to years of eating from jars of fruits and vegetables. A spoonful of chowder may be given to us by our parents, or we may order a bowl to mirror them. For those holding an aversion to an ingredient it can take time. A friend of mine did not have chowder till age twenty. Another hesitates: the broth is a reminder of mayonnaise. But for those on track, each chowder strengthens the ability to distinguish the good from the bad. In our patterns of eating we each string up sets of different bowlspreferences brought by circumstance and expectation. Some may enjoy cream chowders their whole lives and never sway from the habit. Others may jump between the milk and the water and find themselves never liking clams over cod or corn over haddock. Pulling at this line can bring any bowl back.

A middle-aged couple dining by the Cape Cod Canal finished up two plates of fish and chips before going on their way. I placed an order and took a seat as the air came through the door closing behind them. A bowl of chowder and fritters came to the table. Grease poured through the bag. I dumped in a packet of crackers and ate it, then used a napkin. There was an employee in his twenties sitting a table away. He was having a hot dog and reading the paper on a break. He complained about the last shift. He was looking for a new job. We talked about chowder. He asked, Is it really from New England?

Chowder Begins

For New Englanders, and those who would be ones, chowder is a sea swell of the soul. A bowl of chowder (never a cup) evokes a forgotten day years ago, a slanted shaft of light on a wooden table, a stove-top pot steaming as the languorous hours of an autumn afternoon drift toward revelation. Chowder recalls a breeze-swept shore, a celebration of friends and walkers-by decked out in rain gear and wool, seasoned with salt and sand and shocks of briny kelp. For Henry David Thoreau, chowder was the culmination of a day in his beloved Concord woods; for Herman Melville, it sang of the friendship of unlikely shipmates discovering the fishiest of all fishy places, a weathered tavern in the byways of Nantucket. A simmering bowl, a shore-side meal, chowder is sustenance in its most elemental formsustenance of body and minda marker of hearth and home, community, family and culture. So many liquid shades of recall, chowder charts the shoals and eddies of the New England shore and points the way home.

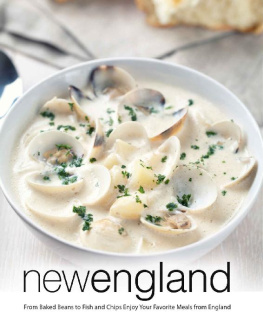

This simple dishthis simple congeries of simple things, cooked simplyis so basic that it is tempting to say what it is not rather than what it is. It is not, for example, a dish for the refined of palate, a bowl for the finicky, the fancy or fussy. It is neither the dainty fare of the elite nor some exotic swaddling thing newly arrived on our national doorstep. It is no adventurous foray into the nether regions of the food chain. Chowder shuns the aesthetic and the summery challenge of spice and heat in favor of wintry grays and whites. It opts for savory over sweet, a layered pot over layered flavor. Salt and pepper, potatoes and onion, pork and fish, cream and hard crackersthere is nothing nouvelle here.

If chowder is elegant, then, it is only so in its simplicity, in its assertive lack of assertiveness. Yet somehow, these scant half dozen ingredients combined have cast a spell over generations of New Englanders. For all its unassuming nature, chowder is defended as fiercely in the region as any national dish has ever been by any ravenous horde. Ask a Red Sox fan about the Yankees, or the Patriots about the Jets, and you will receive a taste of what New Englanders feel about the degenerate soup endemic to Manhattan. New Englanders are bred in the bone with a favorite joint, a favored recipe and a revered chowder master. It is our legacy, our collective memory. In all its varied forms, it is a dish of proportion, substance and balance and can no more be reduced to just another seafood stew than a fine French bread can be reduced to a mere sum of flour, salt, yeast and water. For New Englanders, it has become more than a dish. In its simplest forms, and most elaborate, it is to the region as the madeleine was to Marcel Prousta way of remembering and experiencing a common past, and sometimes creating it.

Next page