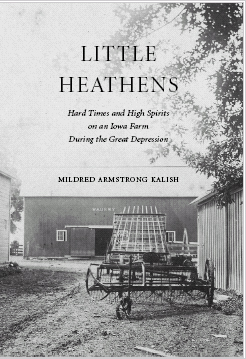

LITTLE HEATHENS A Bantam Book / June 2007

Published by Bantam Dell A Division of Random House, Inc. New York, New York

All rights reserved. Copyright 2007 by Mildred Armstrong Kalish Windmill photograph by Jeremy Menking Schoolhouse photograph by Nancy Ireland Map by Daniel R. Lynch

A Blessing by James Wright from Collected Poems (Wesleyan University Press, 1971) 1971 by James Wright and reprinted by permission of Wesleyan University Press.

Bantam Books is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc., and the colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Kalish, Mildred Armstrong.

Little heathens : hard times and high spirits on an Iowa farm during the Great

Depression/Mildred Armstrong Kalish.

p. cm.

1. Kalish, Mildred ArmstrongChildhood and youth. 2. Kalish, Mildred ArmstrongFamily. 3. Farm lifeIowaBenton CountyHistory20th century. 4. Benton County (Iowa)Social life and customs20th century. 5. Depressions1929IowaBenton County. 6. New Deal, 19331939IowaBenton County. 7. Rural familiesIowaBenton County. 8. Benton County (Iowa)Rural conditions. 9. Benton County (Iowa)Biography. 10. IowaSocial life and customs20th century. I. Title.

F627.B4K35 2007

977.761033092dc22

[B] 2006032730

www.bantamdell.com

eISBN: 978-0-553-90378-2

v3.0_r3

Contents

The people and experiences presented in this book reflect the opinions and observations of the author. A few of the names have been changed to protect the privacy of certain individuals and their families.

Introduction

Aunt Hazel, Aunt Wilma, Mama, and Shep

T his is the story of a time, and a place, and a family. The time was the Depression years, the place a rural area of Iowa, the familymine. To begin it I shall take you back, briefly, to my mothers people, the Urmys, all the way to my great-great-grandparents.

Susannah and Jacob Urmy had the distinction of being among the first pioneers to settle in the state of Iowa. After arriving in Monroe township in Benton County, Iowa, about halfway between Cedar Rapids and Waterloo, sometime around 1846, the year Iowa became a state, they built a log cabin to house themselves and their five children. Eventually they acquired farmland on which they built structures to hold their livestock, as well as a sprawling, no-nonsense, clapboard house that still standsthough in a sad state of disrepairand is known as the home place. They also bought a substantial part of the surrounding woodland which, in a nod to their past, they named Yankee Grove, for they themselves were Yankees, having come to Iowa in a covered wagon by way of Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Kentucky, and Indiana.

Susannah and Jacob helped establish two churches; broke sod three times in their lives, plowing virgin soil to prepare it for raising crops; and were almost totally self-sufficient. Like other pioneers, they did their own doctoring from home remedies. They raised, butchered, canned, and cured their own cows, hogs, and chickens. They hunted squirrels, rabbits, pheasants, and quail right there in Yankee Grove. They tanned their own leather in a hollowed-out hickory log. For the most part, they mended the harnesses for their horses and repaired their own shoes.

They made their own bread and sometimes ground their own flour of oats and wheat; they ground the corn to feed to their chickens and to make cornmeal mush for themselves. They made their own shirts, knitted their own sweaters, scarves, and socks, and sewed their own aprons, dresses, and night-wear. They patched together and tied their own wool quilts. Their industry and independence were nothing short of astonishing. Ralph Waldo Emerson could have learned a thing or two about self-reliance from my great-great-grandparents.

One of Susannah and Jacobs sons, Jonathan, married Harriet Turner, a pioneer he had met in Indiana. They settled on a farm near Yankee Grove. Family lore has it that Harriet was a descendant of the Mayflower Turners, but that has never been verified. Having each been born to parents who had the fortitude to cover half the continent in covered wagons, Jonathan and Harriet continued in the self-sufficient ways of the pioneer tradition which was their legacy. They produced twelve children. Arthur Urmy, my grandfather, was their first son. I came to know Grandpa Arthur very well, but Jonathan I met only onceon a very memorable occasion (which I describe later).

Like his parents and grandparents before him, Grandpa Arthur married a pioneer woman, Emma Fry, who was also the descendant of first settlers in Iowa. Both were still in their teens when they wed, and they immediately set up housekeeping on a farm in Monroe Township, about three miles from Garrison. They had eight children. Two boys and two girls died before the age of two; four daughters, including my mother, Merle, and my aunt Hazel, survived.

Emma Frys family, like Grandpas folks, had immigrated to Iowa around the 1850s, crossing the country from Pennsylvania by covered wagon. But by nature the Frys were just about the opposite of the Urmys. They looked at life as a jolly event. They could and did spend money on luxury items. It was Emmas family who provided the young couple with a dowry that included a double set of Haviland china, real silver, and fine bed and table linens. The Frys spent money on chocolate, cosmetics, entertainment, clothing, barbershop haircuts, and even moderate amounts of alcohol, all without consuming themselves with guilt. As a child, my assessment of them was that they were a very cheery bunch of relatives. However, it was the Urmys, not the Frys, who would set the tone of our family life.

Coming from a background firmly rooted in the New England Puritan tradition, the Urmys could easily have served as models for the source of H. L. Menckens definition of Puritanism as the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy. They were a somber lot, generally speaking. To them, life was a serious challenge and they brooked few frivolities. They read the Bible, prayed every day, and entertained themselves by critiquing the ministers Sunday sermons and quarreling over his interpretations of the Bible. One perpetual topic of debate was whether miracles were still happening, for God was real to them and His actions a source of constant interest and discussion. Anyone careless enough to lay a knife or a pair of scissors on my grandparents Bible could expect a hard knuckle rap on the head, for we were taught to respect God and His word above all else.

It was into this background that my mother, my two brothers, my baby sister, and I were precipitously thrust when I was little more than five years old. The year was around 1930. The Depression was imminent, as was the terrible weather that would become known as the Dirty Thirties. Hard times were going to be especially difficult for us in the decade that followed, for we were without a breadwinner, and would be completely dependent on the largesse of Grandma and Grandpa Urmy, two very strict and stern individuals. For us children, building character, developing a sense of responsibility, and above all, improving ones mind would become the essential focus of our lives.

Next page