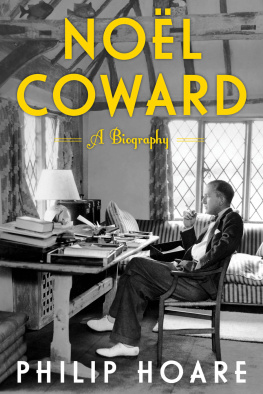

Nol Coward

COLLECTED PLAYS: TWO PRIVATE LIVES, BITTER-SWEET,

THE MARQUISE, POST-MORTEM The plays in this volume demonstrate the extraordinary skill and versatility Cowards writing achieved in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Four characters and a maid suffice for Private Lives Mr. Coward, as the wayward Elyot, and Miss Gertrude Lawrence, as his Amanda have been married and divorced and, when they meet on their new honeymoons, each with a dullard attached, they naturally renew old acquaintance and old strife The combination of the characters is perfect. (Observer, 1930) Of Bitter-Sweet in 1929 James Agate commented that Coward could not quite take credit for the entire production though he could fairly be held responsible for the plot, the dialogue, the lyrics, the melodies as originally executed on a baby grand, the stagecraft, the evenings irresponsibility, wit, and fun, the power to conceive its visual and the general notion of what makes a thoroughly good light entertainment. Last night, said the Morning Post of 17.2.1927, an eighteenth-century comedy by Mr. Nol Coward, entitled The Marquise, was performed for the first time, and a very amusing and well-constructed piece it proved to be delicious and done with dexterity and delicacy.

In 1930 I wrote an angry little vilification of war called Post-Mortem, explained Coward; my mind was strongly affected by Journeys End, and I had read several current war novels one after the other. I wrote with the utmost sincerity: this, I think, must be fairly obvious to anyone who reads it. in the same series

(introduced by Sheridan Morley) Coward

Collected Plays: One

(Hay Fever, The Vortex, Fallen Angels, Easy Virtue) Collected Plays: Three

(Design for living, Cavalcade, Conversation Piece,

and Hands Across the Sea, Still life, Fumed Oak

from To-Night at 8.30) Collected Plays: Four

(Blithe Spirit, Present Laughter, This Happy Breed,

and Ways and Means, The Astonished Heart, Red Peppers

from To-Night at 8.30) Collected Plays: Five

(Relative Values, Look After Lulu!,

Waiting in the Wings, Suite in Three Keys) Collected Plays: Six

(Semi-Monde, Point Valaine, South Sea Bubble,

Nude With Violin) Collected Plays: Seven

(Quadrille, Peace in Our Time,

and We Were Dancing, Shadow Play, Family Album,

Star Chamber

from To-Night at 8.30) Collected Plays: Eight

(Ill leave It to You, The Young Idea, This was a Man) also by Nol CowardCollected Revue Sketches and ParodiesThe Complete Lyrics of Nol CowardCollected VerseCollected Short StoriesPomp and Circumstance

A Novel Autobiographyalso availableCoward the Playwright

by John LahrNol Coward

COLLECTED PLAYS

TWO PRIVATE LIVES BITTER-SWEET THE MARQUISE POST-MORTEM

Introduced by Sheridan Morley

CONTENTS

This second volume of plays by Nol Coward opens with the one which more than any other represents his greatest claim to theatrical permanence. Though it is the lightest of light comedies.

Private Lives has about it a symmetry and durability that have assured it near-constant production in one language or another from the time of its first production in 1930 to the present day. It is in many ways a perfect light comedy, arguably the best to have come out of England in the first half of the twentieth century; and though when it first opened in London many critics reckoned that

Private Lives could only survive for as long as Gertrude Lawrence and Coward himself played it, the comedy has in fact proved almost consistently successful ever since, a guaranteed copper-bottom audience-puller that had temporarily rescued countless repertory companies from the throes of a bad season.

Suitably enough Private Lives was also the play which, given a 1963 production by the Hampstead Theatre Club, launched in Nols own lifetime the sudden revival of interest in his work which he himself gleefully christened Dads Renaissance. Yet Private Lives, though it has indeed far outlived its original production, is a comedy that, even more than most others by Coward, stands or falls by the way it is played. On paper, one discovers, there is really only a kind of code for actors: brief staccato lines, the very occasional aphorism (women should be struck regularly, like gongs) and duologues that when spoken take on a sparkling life of their own. The dialogue in this comedy of appealing manners is theatrically effective rather than naturalistic: there is virtually no action beyond a fight at the end of Act Two and another at the end of Act Three; there are no cameo characters to break up the duologues except for the maid, and there is really no plot to sustain the actors if their talents start to fail them. This is in fact a technical exercise of incredible difficulty even for accomplished light comedians. The roots of Private Lives Me in a very different Coward script also published in this volume: originally he had intended the operetta Bitter-Sweet to be a vehicle for his old child-actor friend and revue partner Gertrude Lawrence, but when it became clear that her enchanting yet somewhat erratic voice could not possibly sustain so operatic a score, he took it away and promised a play for her instead.

Late in 1929 he was setting off on one of his many world tours when, as he recalled in his autobiography Present Indicative, Gertie had given a farewell party for me and, as a going-away present, a little gold book from Carriers which when opened and placed on the writing table in my cabin disclosed a clock, calendar and thermometer on one side and an extremely pensive photograph of Gertie herself on the other. This rich gift, although I am sure prompted by the least ulterior of motives, certainly served as a delicate reminder that I had promised to write a play for us both. But that might well have been the end of that, had it not been for a sleepless night at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo a few weeks later: the moment I switched out the lights, Gertie appeared in a white Molyneux dress on a terrace in the South of France and refused to go again until four a.m., by which time Private Lives, title and all, had constructed itself. In 1923 the play would have been written and typed within a few days of my thinking of it, but in 1929 I had learned the wisdom of not welcoming a new idea too ardently, so I forced it into the back of my mind, trusting to its own integrity to emerge again later on, when it had become sufficiently set and matured. A few weeks later, when Coward had reached the Cathay Hotel in Shanghai and was recovering from a sudden bout of influenza, the idea by now seemed ripe enough to have a shot at, so I started it, propped up in bed with a writing-block and an Eversharp pencil, and completed it, roughly, in four days. It came easily, and with the exception of a few of the usual blood and tears moments, I enjoyed writing it.

I thought it a shrewd and witty comedy, well constructed on the whole, but psychologically unstable; however, its entertainment value seemed obvious enough, and its acting opportunities for Gertie and me admirable, so I cabled to her immediately in New York telling her to keep herself free for the autumn, and put the whole thing aside for a few weeks before typing and revising it. There followed, as Nol later recalled, a tremendous telegraphic bickering between himself and Gertie: She had cabled me in Singapore, rather casually I thought, saying that she had read

Next page