Contents

Guide

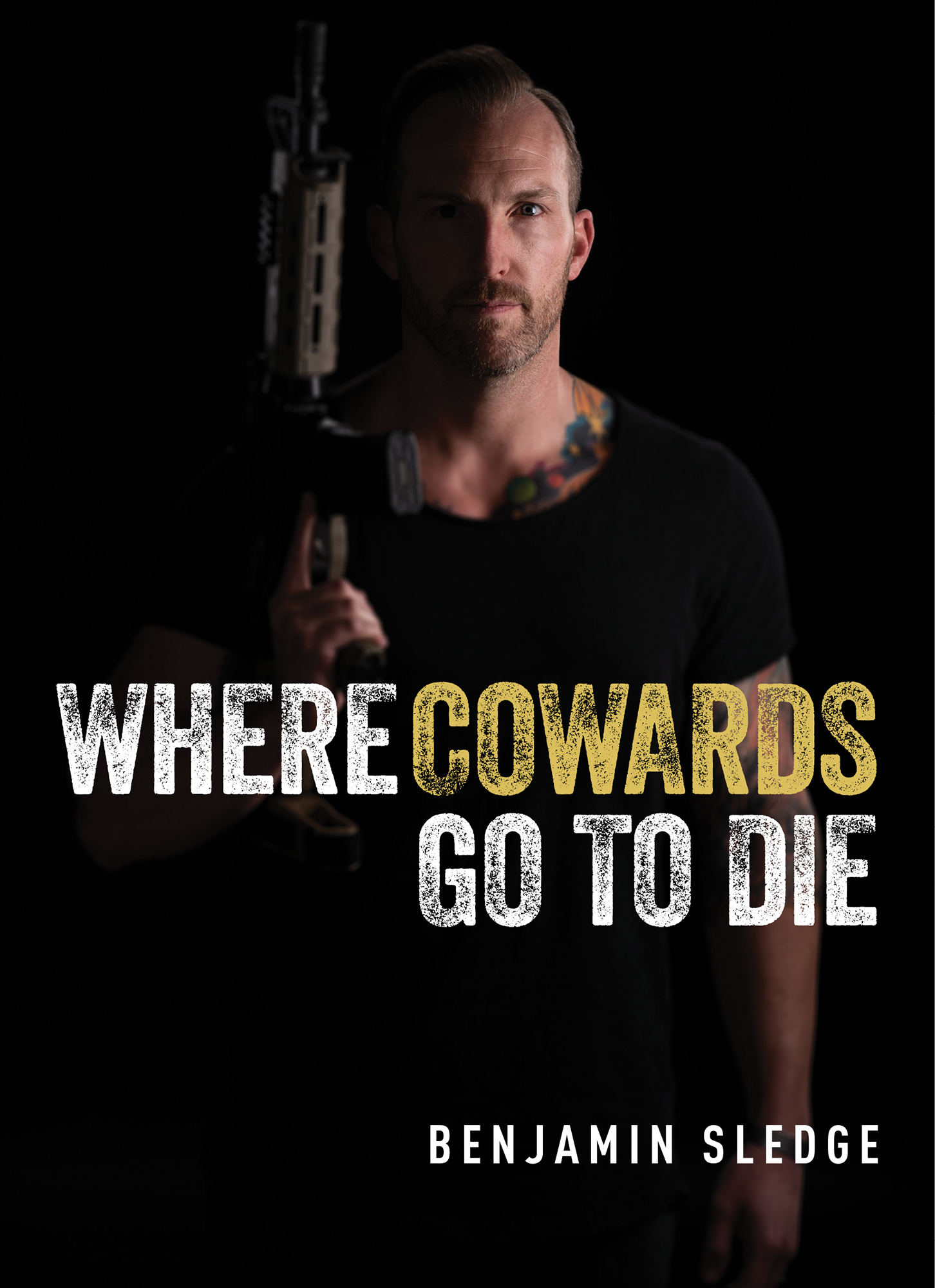

Where Cowards Go to Die

Benjamin Sledge

Copyright 2022 Benjamin Sledge

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, website, or broadcast.

Regnery is a registered trademark of Salem Communications Holding Corporation.

ISBN: 978-1-68451-164-8

eISBN: 978-1-68451-311-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022937354

Published in the United States by

Regnery Publishing

A Division of Salem Media Group

Washington, D.C.

www.Regnery.com

Books are available in quantity for promotional or premium use. For information on discounts and terms, please visit our website: www.Regnery.com.

The events, places, and conversations in this memoir have been recreated from memory, referencing journal entries, extensive interviews, and reviewing maps. The chronology of some events has been compressed. When necessary, the names and identifying characteristics of individuals and places have been changed to maintain anonymity and protect their identities due to the nature of their work in the Armed Services or otherwise.

Cover design by John Caruso and Benjamin Sledge

Author cover photo by Jonathan Betz

For Kyle,

and for my children who will one day ask,

Daddy, what was it like to go to war?

1 Walk with Me in Hell

Afghanistan, 2003, seven months into combat operations

T he blood pooled into small concentric circles to the left of the child. Normally, I would have found his wheezing annoying, but I could only watch as he gasped for breath. Like a gargoyle frozen in time, I hovered over the boy while he stared, wide-eyed, into the dismal blue sky.

Explosions peppered the landscape around me while a medic held a large-bore needle over the boy, flicking the end. Before he could jam it into the childs chest, I found my feet and ran.

As I rounded a corner, I spotted a man in camouflage standing atop a large HESCO barrier filled with dirt and exclaiming, Holy fucking fuck! Its a good day to die! Some nearby soldiers laughed. I slowed my pace and chuckled, too, as the absurdity of war unfolded around me. Seven months of combat in Afghanistan will do strange things to a guys sense of humor. Besides, all explosions considered, it was a good day to die. Despite the bitter winters of the Afghan mountains, the sun had warmed the air to a cool 50 degrees. Not having enough time to pull on pants or a cold- weather jacket, I wore a dirty brown shirt, body armor, and black shorts skimpy enough to make your sister blush.

The base had suffered a heavy barrage of attacks the past few weeks, with the Ramadan Offensive unfolding over much of November 2003. Theres nothing worse than the potbellied stove you use for warmth exploding because an enemy force blew it to smithereens, the remnants of your heating device embedded either in the walls or your friends. Dead friends and shattered heaters wont keep you warm. Apparently, neither will catch-me-fuck-me shorts and a stained T-shirt.

Once I neared the bases Tactical Operations Center (TOC), I burst through the door alongside my team chief, Paul Gonzo Gonzalez. Inside, frantic chatter and yelling punctuated the air. Having recently shaved his beard, Gonzos grimace was even more accentuated than usual. He was not a man to be trifled with despite his relative youth. Soldiers cleared his war path while they chattered away on radios, directing troop movement. Not that any of it mattered. The men attacking the base were hidden in the mountains, well concealed and with escape plans that made them impossible to find.

The room continued in a tizzy while I stood still, trying to shake the memory of the Afghan boy with a hole in his chest. Id seen worsemen with their faces caved in, guts spilling out like worms onto the seat of a blue Toyota Hiluxbut a hurt child always tore the soul, no matter how minor the injury.

As I awaited orders, I tried to distract myself by checking my magazine, ensuring the cartridges were still there. They were, but I loaded a new magazine anyway. More often than not, weapon malfunctions come from magazine cartridges that have ammunition in them for too long. The spring relaxes and isnt as forceful, so the bullets wont enter the chamber. If it was indeed a good day to dieas the man atop the barrier proclaimedbetter to go down firing than fiddling with a jammed weapon.

No parents want to hear that the enemy killed their son as he tinkered with his rifle. Let us go down in a blaze of gloryRambo styleas bullets riddle our bodies. The way everyone imagines it is like a scene from a movie. We bleed out of the corner of our mouths while saying something profound, and then our eyes go dim. It never happens that way, though. Once youre dead, the body evacuates your bowels. Here lies Benjamin Sledge. Empty magazines and colon.

Once Gonzo returned from a quick briefing, I examined his face to get a read on the situation. His countenance had a severe edge to it, an expression he tended to wear when something irked him.

Ill stay here and communicate with the team in Kandahar, he told me. You and the intel guys will round up the locals and get them to safety.

I opened my mouth to ask for more information but a loud, short whistle screamed over the TOC with just enough time for someone to yell Incoming! I flinched while Gonzo stood tall, unimpressed by the attack. He pointed to the door and gave me my orders. You got this, Hollywood. Now, move.

Doors in Afghanistan are strange. In the United States, theres a standard everyone seems to follow: doors are shaped like rectangles. In Afghanistan, they have optionsrectangle, Hobbit-sized, or slim bat-wing doors. The TOC had the bat-wing doors, so every time you entered, it felt like you were walking into an old Western saloon. In theory, this is cool, but practically, the doors are so narrow that you have to wedge yourself through, and half the time your rifle strap catches, choking or stalling your grand arrival as you fumble to break free.

As I burst through the bat wings into the chill air, true to form, my strap caught. I tugged repeatedly, doing nothing to free myself but adding to the frustration and fear ebbing through camp.

The problem with war movies is theyre sort of accurate. Everyones yelling, and youre hyperaware of your own breath. Nobody has a clue what hes doing, either. You make it up as you go, the muscle memory from training taking over. And even when youre sprinting, it feels like youre trudging through quicksand in slow motion. Once I freed myself from the TOC doors, I forced my tree-trunk legs forward and into the chaos.

The outpost where we were stationed sat nestled in a valley between two mountain ridges. For all the talk of the Armys being tactical, this was the dumbest location for a small outpost with fewer than three hundred soldiers. The mountains nearby were full of caves and escape routes, which the Afghans had been using since the Soviet-Afghan War in the 1980s. The logic behind our location was that we were in close proximity to Orgun-E, Afghanistan. This allowed us access to diplomatic relations with tribal elders, intelligence, and reconnaissance. It also helped us keep a watchful eye on the border with Pakistanat least, in theory.