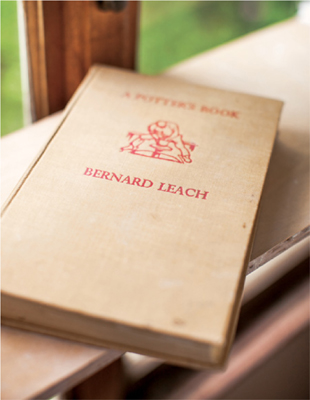

Look to combine beauty and function in a pot. BERNARD LEACH

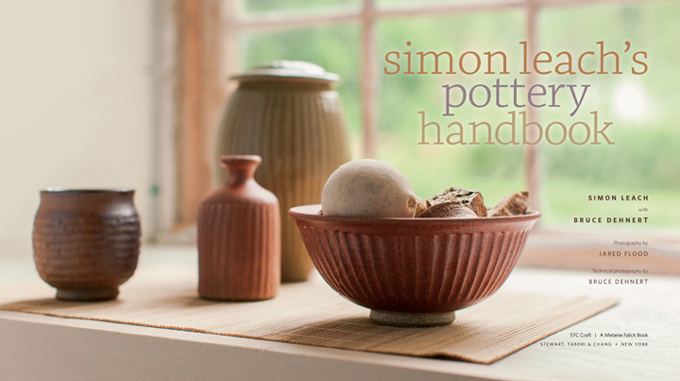

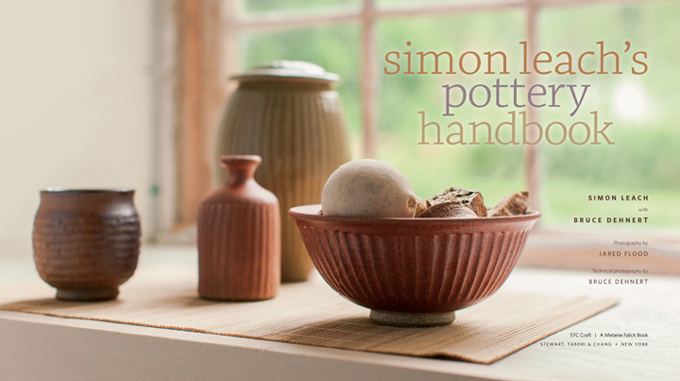

Published in 2013 by Stewart, Tabori & Chang

An imprint of ABRAMS

Text copyright 2013 by Simon Leach and Bruce Dehnert

Photographs on the following pages copyright 2013 by Jared Flood:

Photographs on the following pages copyright 2013 by Bruce Dehnert:

Photographs on the following pages copyright 2013 by Simon Leach:

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Leach, Simon.

Simon Leachs pottery handbook / by Simon Leach with Bruce Dehnert.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-61769-022-8 (spiral bound)

1. PotteryTechnique. I. Title.

NK4225.L43 2013

738.14dc23

2012042757

Editor: Liana Allday

Designer: Susi Oberhelman

Production Manager: Tina Cameron

115 West 18th Street

New York, NY 10011

www.abramsbooks.com

Some of the activities discussed in this book can be very dangerous. Any person should approach these activities with caution and appropriate supervision and training. The publisher and author are not responsible for any accidents, injuries, damages or loss suffered by any reader of this book.

contents

introduction

I wrote Simon Leachs Pottery Handbook, along with my friend Bruce Dehnert, to share my thirty-plus years of pottery experience with those aspiring potters who are both excited about and daunted by the craft. Early on in my vocation, I was fortunate to apprentice with my father, David Leach, and then move on to set up studios in England, Spain, and presently in the U.S. If I can impart some of what Ive learned over the years to those who are learning to throw pots, then I am happy to do so.

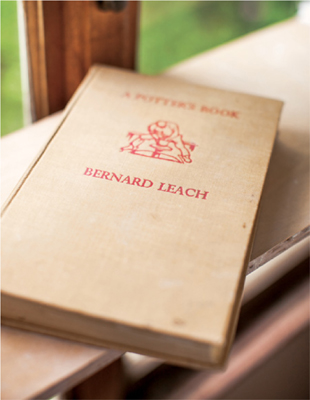

My role in the world of ceramics may seem to have been predestined, coming from a line of potters in England that started with my grandfather, Bernard Leach (18871979), who is known as the father of studio pottery. As a child on summer holidays from school, I was often driven by boredom and curiosity to wander into my fathers pottery studio in order to watch the apprentices at the wheel. We always had a bit of fun on those days as the apprentices threw pea-sized clay balls at my bare legs while I laughed, jumped, and hid to avoid being hitthat is, until my father entered the studio and chased me away (I was quite a distraction for his workers).

But as I grew older, my favorite hobby was making model planes out of balsa woodnot pots out of clayand by the time I completed my studies at boarding school, I had no thoughts really to follow in my fathers footsteps. Instead I entered an engineering apprenticeship at a helicopter manufacturer. The four long years I worked there came to feel like a prison sentenceI was just a machine doing repetitive work in an atmosphere that I didnt likebut eventually an opportunity for escape came along. The company was downsizing and offered redundancy pay to employees who would volunteer to leave, so I took the offer, more than ready to start a new adventure.

Off I went traveling around Europe, from Greece to Spain, gathering stories from these colorful places and having inspirational conversations along the way. Eventually the money ran out, so I asked my father if I might work for him at his pottery in Lowerdown, in Devon, England. I was thinking I would work in the pottery for six months and then have enough saved to go on my next trip, but as it happened, I wound up apprenticing with my father for five years. During that time my father came to depend on me, and he was full of compliments as I gained skills in pottery. I came to feel a sense of accomplishment and felt quite at home in the studio, so it seemed natural for me to stay on working there.

During the early years of learning the pottery business at his side, I was given exercises, meaning that I was often asked to make multiples of a specific form. It was through these exercises that I began to appreciate the benefits of repetitive throwing. Over time, I noticed that the walls of my GP (general purpose) bowls became more consistent, and the lips of teapot spouts were cut and attached just right so they poured well. Eventually, I got the hang of what was expected of me, and in September of 1984, my father asked if I would be interested in running the pottery. With his question, I felt a bit put on the spot. While my time there was invaluable and my dad was a very good teacher, he had firm ideas about how things should be done, and I thought I would never really have the freedom to see my own ideas come to fruition. I told him I thought it was time to start working for myself. With that decision, I was suddenly faced with the freedom of making whatever I wanted. I felt both excited and daunted, but this was my path to pottery... one that I finally came to embrace.

I set up my first proper pottery studio in the Devon village of Silverton, and it was my first taste of being on my own. My pots were not radically different than my fathers, except that I embraced the process of raku firing. Overall, life was good. I was content enough to carry on there for the next four years, and along the way opportunities arose to exhibit my work. I had no complaints except for the English weather (around that time, I remember two really atrocious, damp summers in a row). Yearning for sunshine, and remembering my travels to Spain in the late 70s and early 80s, I thought this might be a place where I could settle with my family, so off we went. I lived in Spain for nineteen years before relocating to the United States in 2009.

Selling pots was only one of the ways I earned my bread and butter. I also began teaching workshops from my studio in Spain. One day I thought to film myself throwing on my Leach treadle wheel, and when a friend saw the video, he said to me, Simon, why dont you put up a clip on YouTube? In 2007, YouTube was fairly new technology, and I didnt have much in mind other than it being a novelty. I think the first clip I posted was of me throwing dinner plates. Soon enough, potters around the globe started posting comments. At the time, I was working in rural Spain with little or sometimes no interaction with other potters, so I thought this was just great. YouTube was a window to the world, and I found when I got in front of the camera, I had a lot to say and share about general pottery studio practices. So I continued making clips, and today there are more than 800 of them on YouTube.

Next page