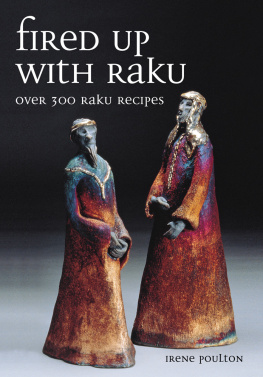

MASTERING

KILNS & FIRING

RAKU, PIT & BARREL, WOOD FIRING, AND MORE

Lindsay Oesterritter

FOREWORD BY JOHN NEELY

FOREWORD

When beginners take up ceramics, they are seldom aware of all that the subject entails. The struggle to impose form on a formless lump of clay is trouble enough. How to finish a hard-won form is too often an afterthought. And yet, it is not until that clay has been fired that it gains utility or permanence. In shorthand, one can simply say that clay + fire = ceramic. It is the second element in this equation, fire, that is the subject of this book.

In our push button contemporary world, it is possible to buy equipment that brings electric stove convenience to the heat treatment of clay. The fact that in English we call this heat treatment firing, though, is deeply significant. Electric kilns, for all of their convenience, come with many limitations. There are many ceramic processes that require the action of a live flame. Lindsay Oesterritter came to this realization early in her ceramic career, building kilns and firing with wood almost immediately. The research and experimentation she has engaged in over the years have had a profound influence on her studio work, and, in great measure, shaped this book.

My own involvement in ceramics began in high school, and I, too, soon found myself using wood as a fuel. This was spurred in equal parts by a fascination with the history of the medium and a fascination with fire and flames, the same urge that leads us to peer into campfires, stir the coals, and tell stories. Of course, for most of the history of ceramics, wood and other plant materials were the only fuels available. Some relatively treeless places like northern China adopted coal as a fuel, but coal, too, is ultimately of plant origins. It was coal that fueled the industrial revolution, and coal was added to the western potters arsenal at about the same time. Petroleum technology came along by the end of the nineteenth century; electricity came into wide use only in the twentieth century.

When I took up a teaching post at Utah State University some thirty-five years ago, acquiring kilns was the first order of business. That I had no budget was also a factor, but as I tried to construct a curriculum, it seemed to me that wood firing had the potential to play an important role. It was clear to me that students who use the same means of production as their historical antecedents would have a different understanding of both history and technology. Wood firing connotes rather more than the heat treatment of ceramic objects. There exists around wood firing a complex of concerns only peripherally related to the objects fired. I find the wood kiln useful as a teaching tool just because it stimulates discussion and understanding of these concerns.

Wood firing students have a greater understanding of the value of the work they docertainly they gain a direct understanding of the amount of biomass that must be sacrificed to make their pots permanent. They learn with their bodies the kilocalories or BTUs and work hours that it takes to make a coffee cup hold coffee. This particular issue will only grow in significance in the future. As we deplete our stocks of fossil fuels, renewable resources will be our only alternative. Wood, as a method of harvesting solar energy, seems likely to stay in the mix of viable options for the foreseeable future.

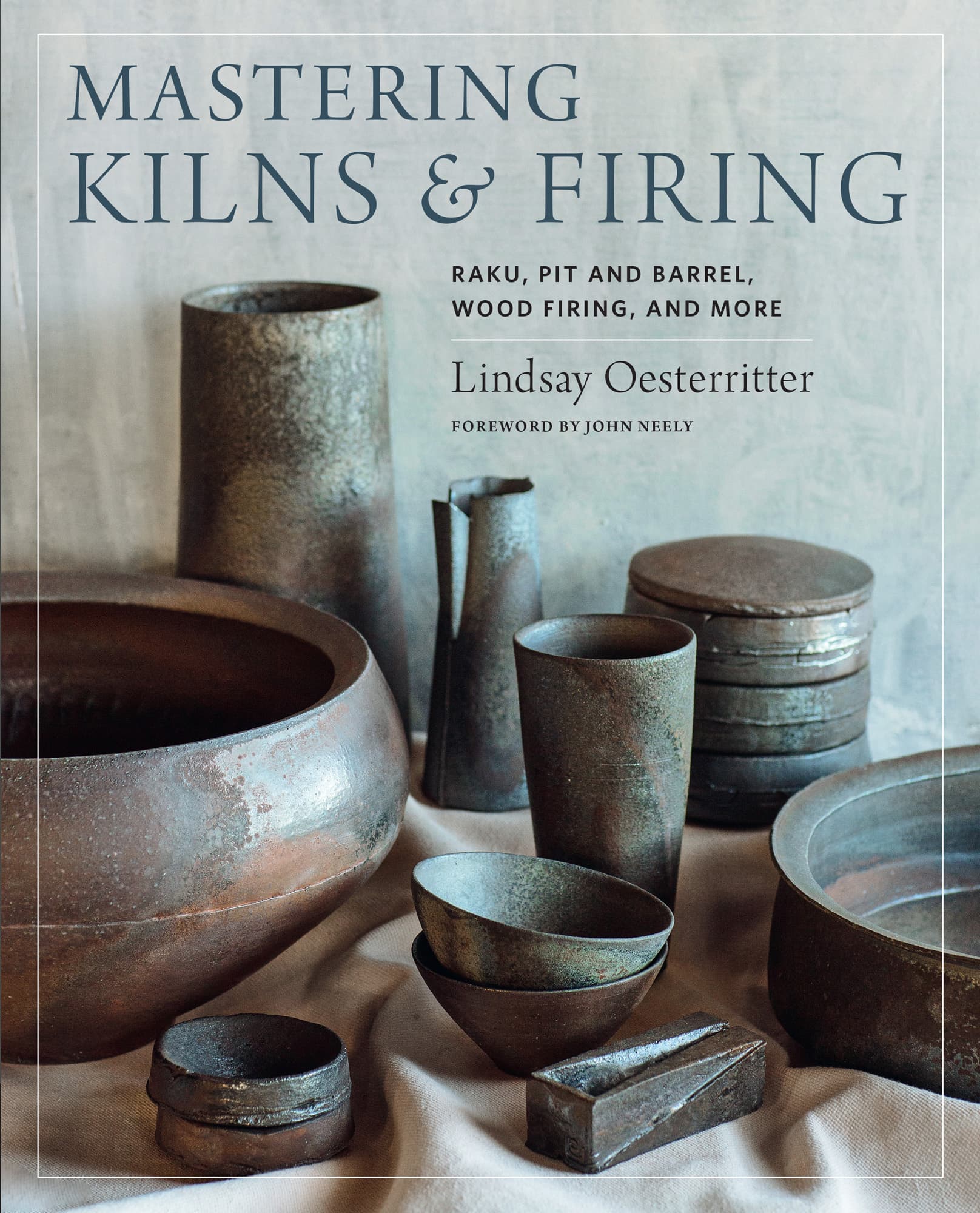

The best reason for the use of wood firing and the related processes of raku and pit and barrel firing, however, is aesthetic. Michael Cardew, writing in Pioneer Pottery observed that There are certain subtleties and qualities of color, texture, and depth which wood firing, properly managed, will give you as a free gift. I do not doubt that this glow of life in pots and glazes can also be obtained using other fuels, but I am sure that it is much easier to achieve it with wood. There are surfaces, textures, and colors that are possible with no other methods of firing. This book provides the reader with a solid introduction to the use of live flame and allows us to amend the ceramic equation to read clay + fire + know-how = beautiful ceramics. To truly master kilns and firing is a lifelong endeavor, but with Lindsay illuminating the path, aspiring potters will soon be on the way.

JOHN NEELY, potter and professor, Utah State University

INTRODUCTION

I built a kiln in my backyard because I needed a kiln to make a living. My style of firing is specialized enough that sharing a kiln with another potter is difficult. However, from the start, building that kiln has been rewarding in ways I never imagined. Beyond the obvious satisfaction of a successful firing, I was pleasantly surprised at how it helped strengthen my own community.

The build started with the timber frame kiln shed. My husbands father and stepmom came out for several weeks to help chisel the joinery, so even this part of the build brought in family and friends. Since our family was new to the neighborhood, we decided to turn our shed raising into a partya nice way to get to know our neighbors and get help with the heavy lifting. When it came time to build the kiln, I worked with my good friend and kiln builder Ted Neal and a few local volunteers. After the first firing, I gifted all the neighbors that helped with the build a mug as a thank-you present. The communal nature of firings has continued to this day. With each firing, we invite friends and neighbors over to hang out by the kiln. I have also found new wood sources in neighbors knocking at my door after cutting down oak trees or because they know someone who is looking to get rid of rounds.

No matter the kiln you are thinking about building or the firing process you are thinking about exploring, it is sure to foster a community of makers (and friends of makers). Alternative firing requires a little more attention by the kiln, a little more patience by the fire, and a genuine love of the process. My goal in writing this book is to make alternative firing techniques and ideas approachable for everyone, including beginners and enthusiasts. Along with tips from my own studio and firing experience, throughout this book there are artist features from talented makers highlighting additional processes and materials, and gallery artists that showcase the limitless potential and possibilities within alternative firing.

I will introduce a variety of firing techniques, including raku, pit and barrel, and wood firing. These chapters are process-based, focused on helping eliminate some of the mistakes many of us made as beginners. The goal is to give you a framework from which to start your own fire! I will also cover kiln design basics, to help you better approach and assess kilns you might come across in community studios, workshops, and classes. If you are thinking about building your own kiln, along with considerations for design, Ill cover some of the personal and practical matters of designing and building that kiln. In the final chapter, Ill introduce a few ways to experiment with kilns and firings to add to your studio practice.