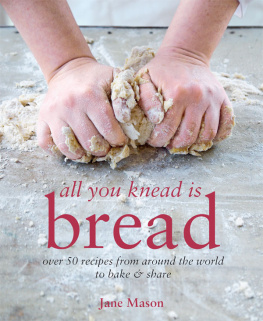

This book is for my parents, who taught me how to love cooking, baking and eating.

Picture Editor Iona Hoyle

Picture Researcher Christina Borsi

Production Manager Gordana Simakovic

Art Director Leslie Harrington

Editorial Director Julia Charles

Prop Stylists Risn Nield and Tony Hutchinson

US Recipe Tester Susan Stuck

Indexer Hilary Bird

First published in 2012 by

Ryland Peters & Small

2021 Jockeys Fields

London WC1R 4BW and

519 Broadway, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10012

www.rylandpeters.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

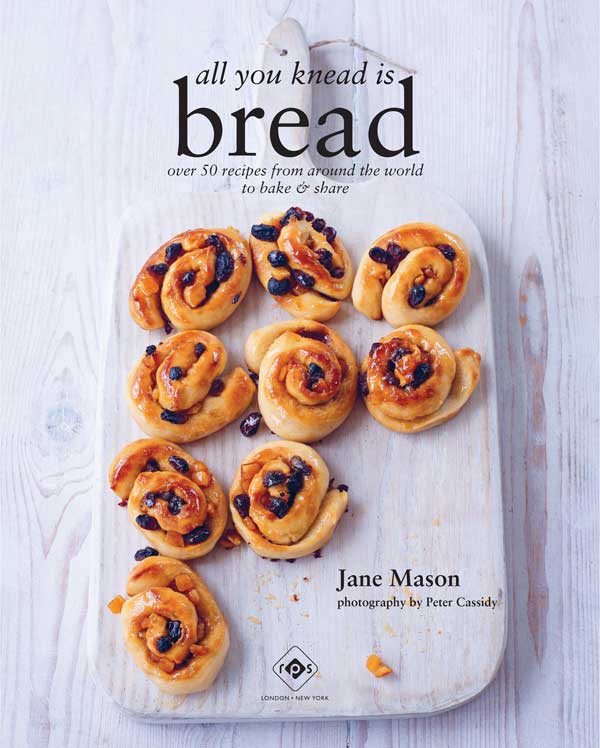

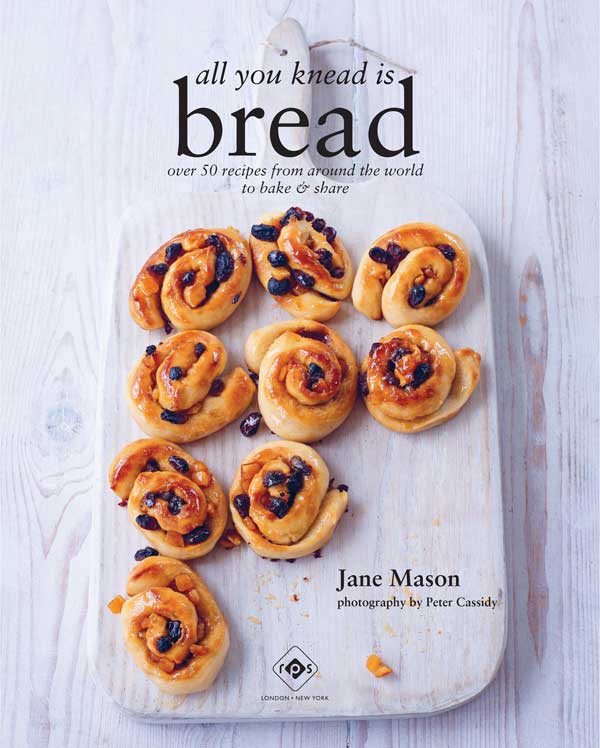

Text Jane Mason 2012

Design and commissioned photography

Ryland Peters & Small 2012

Printed in China

The authors moral rights have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

eISBN: 978-1-84975-397-5

ISBN: 978-1-84975-257-2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

A CIP record for this book is available from the US Library of Congress.

Notes

All spoon measurements are level unless otherwise specified.

All eggs are medium (UK) or large (US) unless otherwise specified.

Ovens should be preheated to the specified temperatures. All ovens work slightly differently. We recommend using an oven thermometer and suggest you consult the makers handbook for any special instructions, particularly if you are cooking in a fan-assisted/convection oven, as you will need to adjust temperatures according to manufacturers instructions.

Contents

About a zillion years ago, early humans crushed up grains, kernels and seeds, mixed them with water, and cooked them to make something to eat. What they crushed determined what they ate both at the beginning of time and several thousand years later when we first started to bake.

The story of bread in our lives is at the heart of three other stories: grain, travel and settlement. Grain because most bread is made out of grain; travel because nomads, early explorers, conquering armies and settlers carried what they needed when they moved around, and integrated what they found into their lives if it enriched them; and settlement because peace and prosperity enabled bakers to develop their craft, making bread delicious and beautiful as well as functional.

Today, wheat is one of the largest cultivated grain crops, and the main ingredient in the vast majority of bread that is eaten around the world. This indicates simply that it grows like a weed. From its birthplace as a cultivated grain somewhere between what were then Mesopotamia and Eastern Anatolia/the Western Armenian Highlands around 6,000 BCE, wheat has conquered almost the entire world, moving around the fertile crescent, across to Asia, up to Europe, and over oceans to the Americas, Australia, Africa and New Zealand. There are few places where wheat and bread made from wheat flour have not thrived.

There are plenty of other grains in the world including amaranth, barley, buckwheat, corn, flax, millet, oats, quinoa, rice, rye and teff. They are all delicious and nutritious and are used to make all sorts of food including bread. However, some require special growing conditions (water, cold, heat or altitude), others originated in countries that neither spawned nor experienced the kinds of explorers who popularized these grains in the way wheat has been popularized, and none can be stretched to create the variety of shapes or the fluffy light texture that are associated with stability. Only wheat can do that.

The mass movement of people in the last hundred years no longer spread grains and seeds, but it has spread bread. Most immigrants miss bread more than anything else in their countries of origin and, once established in new homes, many set up bakeries and introduced their bread and bread customs to their new home countries. This is why you can get tortillas in China, steamed buns in Paris, baguettes in Delhi, naan bread in Rome, ciabatta in Hamburg, rye bread in Montreal

Sadly, highly processed bread, rapidly baked by plant bakers has also marched around the world. Square, spongy and soft, this product smells a bit like vinegar, forms a gooey ball if you squeeze it, sticks to the roof of your mouth when you eat it, and simply does not taste like bread. It is time that we demanded something better, or started baking bread ourselves.

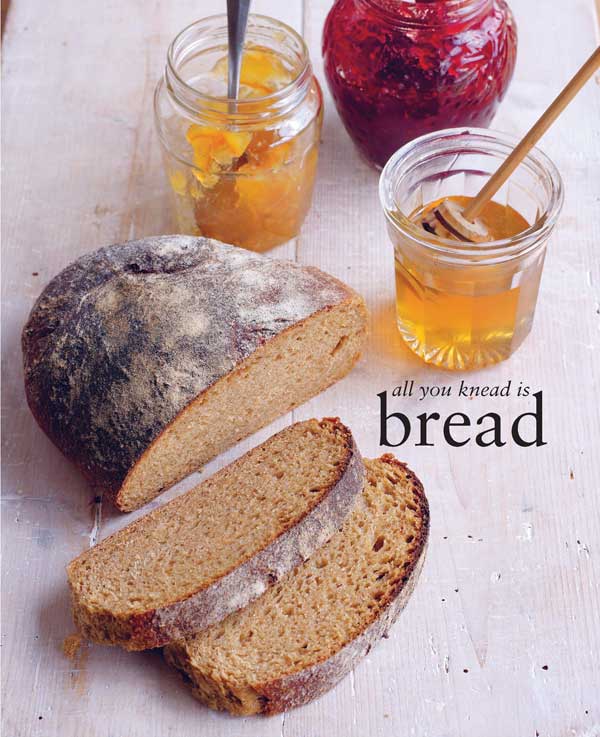

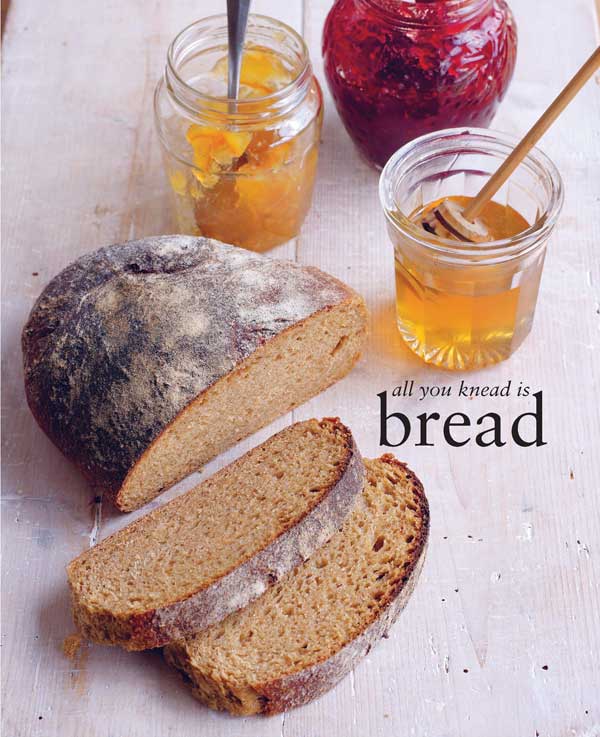

Bread is a basic staple, an occasional treat, an inexpensive luxury and a key part of celebration and ritual. It is a metaphor for money and, in many languages, the words for bread and life, joy and celebration are interchangeable. Bread is the stuff of story, song and poetry, and is a symbol for everything that is basic and necessary. To waste bread is a sin. To make and share it is a blessing. On their own, the basic ingredients flour, water, salt and yeast do not sustain us. They are only life-giving when combined. Good bread is the result of responsible farming, gentle milling, an element of hand baking and local delivery with minimal packaging. It is a window into culture, affirming both our individuality and humanity.

Observing this makes it clear that the decisions we take about the kinds of bread we make, buy and eat can change the world for better or worse.

Basic bread is made of flour and water. Yeast makes it rise and salt makes it taste better. Out of these ingredients you can make endless varieties of bread. You can expand your repertoire exponentially if you choose to add and/or substitute ingredients. You dont have to be an expert before you substitute wine for water or add raisins. However, there are a few things you may want to know before you begin. They are outlined in the following pages and will be an invaluable guide on you new bread-baking journey.

Flour

You can bake a kind of bread out of almost any flour, although different kinds of flour behave in different ways.

Gluten in flour is like a balloon, expanding as the carbon dioxide is expelled by the yeast. Flour with gluten includes wheat (and its cousins spelt, emmer, kamut and einkorn), rye and barley. Flour that may contain gluten includes oat and hemp (read the label carefully if this is important to you). All other kinds of flour are gluten free.

It is important to know a bit about gluten. Firstly, different types of flour are not necessarily interchangeable and secondly, some people are mildly or severely gluten intolerant. This intolerance, called coeliac disease, affects a small minority of the population and the symptoms can be mild (tummy ache) to severe (neuropathy). This book has some gluten-free recipes for things like fritters, pancakes and skillet bread but does not have recipes for gluten-free bread baked as a loaf. There are some great recipes for this kind of bread in Emmanuel Hadjiandreous excellent book How to Make Bread .

Next page