Conquering Comparisons

for

Better Mental Health

Robert Prior-Wandesforde

Copyright 2020 Robert Prior-Wandesforde

All rights reserved

To those laid low by hurtful comparisons

Nobody can make you feel inferior without your consent

Eleanor Roosevelt

Contents

Introduction

Its All Relative

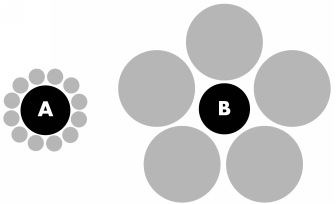

Have a quick look at the images below and decide which of the two central circles, A or B, is the biggest.

The chances are that you chose A or, if you know this trick, neither. The correct answer is B! Circle A only appears to be bigger because we cant help but compare the size of A and B to the other circles surrounding them. If those reference points are removed, as they are overleaf, its apparent that B is (marginally) bigger than A. This is a variant of the Ebbinghaus illusion and has huge relevance to our everyday lives.

Comparisons influence how we see ourselves

Let me ask you a question: how clever are you?

Your answer will probably be determined by how clever you perceive yourself to be relative to an average of some sort. For example, you might know that you have an IQ of 110 and the UK average is 100, leading you to conclude that youre quite clever.

But if you dont believe an IQ test is a good measure of cleverness, you dont know your IQ and/or youre unaware of the UK average youll have to compare yourself in some other way: probably against people with whom you spend most time. As a result, if you generally mix with extremely smart individuals, theres a good chance youll conclude that youre not particularly bright. If, however, the opposite is true, you may well decide that youre clever. The point is, your actual cleverness is the same in both cases but your perception of how smart you are is very different.

This effect was demonstrated in a US study, where pupils assessment of their academic ability was found to be lower in highly selective schools than in less selective ones, adjusting for their actual ability. Why? Because they compared themselves with their fellow students rather than a wider student population. Consequently, pupils in the elite schools were harder on themselves than those with the same intelligence who happened to attend other schools.

Profound practical implications often follow as a result of such judgements. Lets say were confronted with a difficult mental challenge. The chance of us solving the task will be a lot higher if we perceive ourselves to be clever rather than if were convinced were incompetent. In other words, its not just how clever we really are that determines how likely we are to succeed but, what could be termed, our self-cleverness-perception.

Wanting to test the impact of feelings of inferiority on problem solving abilities, a psychologist presented students with a timed test, informing them that, on average, their peers finished it in one-fifth of the time it actually took them. He then rang a bell at that spurious moment and watched how incompetence set in as the students concluded that they were much worse than most.

As another way of illustrating how important comparisons are in dictating how we perceive ourselves, assume that youre the first human to land on another inhabited planet. An alien, who, conveniently, speaks your language, asks, How clever are you? You might answer this question by saying something like, Well, from where I come from, most people say Im smart. The trouble is this means precisely nothing to the alien who hasnt met anybody else from your planet. He then enquires, How strong are you? Are you good at drawing? Do you find it easy to fix things?

You realise that you have no way of providing meaningful answers to any of the aliens questions. But then you have a brainwave. Lets have an arm wrestle and we can test how strong I am. We can both draw a picture of that rock over there and see which you think is best. After that, we could time how long it takes each other to mend something.

Having completed the tasks, the two of you conclude that the alien is both stronger and better at fixing the item than you but not as good at drawing. By making comparisons youve provided answers that the alien can understand, while also beginning to see how you fit into this new world. You begin to believe that youre not that strong or good at fixing things but can at least draw quite well.

The next day, the alien takes you to meet three of his friends and politely requests that you each draw a picture of the landscape. Unbeknown to you he has selected the best artists on the planet and it turns out that your drawing is by far the worst. You decide that youre not particularly good at drawing after all. In fact, with your confidence dented, you start to think that the vast majority of aliens are superior to you in most or all respects. After several similar experiences, you may even come to conclude that youre useless and its best not to do very much at all for fear of being found out.

In many ways, your experience in this thought-experiment is similar to that of a maturing infant, child and adolescent on planet earth. Given that when we enter the world were desirous to explore it and find out about ourselves in the process, were also hard-wired to make comparisons and seek feedback. Our self-image (how we see ourselves) and self-esteem (what we think about ourselves) will be heavily influenced by the results of these comparisons and the reactions we glean from others. If the comparisons are consistently distorted in some way then the same may be true of how we feel about ourselves and, therefore, how we perform and behave.

Relating this to the earlier pictures, if we perceive ourselves to be big relative to those around us (circle A), were in danger of feeling and acting in a superior way. If, however, we think were comparatively small (circle B), then we may feel inferior. It all depends on who we happen to compare ourselves with. The words big and small here could relate to almost anything from our physical height to our ability to play chess to our qualities as a school teacher.

Better comparisons for a better life

In virtually every aspect of our lives, what we think, the way we feel, how we behave and the conclusions we reach are affected by the specific comparisons we make - if we had used different comparisons the outcomes may also have been different. This isnt necessarily a problem if the comparisons are suitable and we react appropriately to them. The trouble is theyre often highly inappropriate, leading us to make mental, emotional and behavioural mistakes. At worst, they can completely blight our lives. This book is about how we can make better comparisons to improve our psychological well-being.

I discuss the sort of comparisons we make and their effects, explore the role of social media, consider what our Target-Selves may look like and how we can progress towards it through our thoughts and deeds. I also consider how to deal better with failure, make habits of our new thoughts and underpin our self-worth.

Chapter 1

Why Comparisons Matter

Born to compare...

My life is so much worse than hers, Im not as good-looking as he is, Im better than everybody else on this team are all examples of social comparisons - the process of thinking about other people in relation to ourselves. According to developmental psychologists weve usually acquired the ability to compare before we can even talk or walk and continue to make comparisons for the rest of our days. Some of us are more active comparers than others, while there will also be periods in our lives when were more inclined to make comparisons. But, like it or not, we all compare and generally do so automatically.