No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers.

Preface

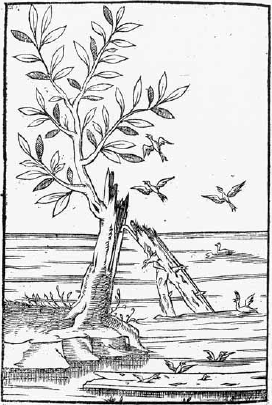

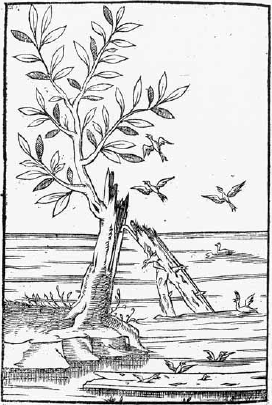

Nature produces them, contrary to her own laws, in a most extraordinary manner. They are like marsh ducks but smaller. They grow in the guise of growths in the trunks of trees that have been washed up on the beach by the sea. As they grow, they hold onto the trunk with their beaks like seaweed adheres to the wood on the beach. Shells protect them so they can grow freely underneath.

What were these marvels? Ducks in a larval stage? Travelling through Ireland in the twelfth century, Gerald of Wales goes on to explain how over time the ducks become covered by a layer of feathers and drop off into the water or fly into the air. He insists that they feed on the sap from the sea itself, allegedly having seen more than one thousand of these little birds hanging from a tree trunk on the beach, lying under their shells and already formed. Gerald observes that certain bishops and prelates in Ireland eat these creatures during Lent because they are not made of meat.

Did Catholic priests, who had no intention of giving up their meat diets for Lent, invent vegetable ducks? A cunning excuse: birds called bernacae found in large quantities all over Ireland, justifying roast duck dinners all through Lent. In 1597 Gerards Herbal referred to the phenomenon again: the ducks special familiarity and ease on land, air or water offers richly confused interpretation:

This fowle vnknowen to the Auncients hath no certeine name amongst the Greekes... Amonge the Latynes... from the branded colour thereof callinge it Branta or Bernicula... In France they call it Crabans or Crauant or Oye Nonnette, the Germanes Baumganss, Wiewolanch, and the Scots Clakis. [It] liveth in fresh waters: sometimes aboue and sometimes vnder.

Claude Durets Portrait of tree with rotting branch which produces mould, then living, flying duck, from his Histoire admirable des plantes et herbes esmervillables & miraculeuse en nature (1605). |

|

Sometimes above and sometimes under: that is the prevailing mystery of duck existing in between the elements, in between reality and imagination, unstable creature that it is.

This book begins with a natural history. The term used to categorize duck tribe is not used with any other avian family but is instead found in plant taxonomy, referring us back to the medieval confusion cited above. We move from what science has classified to matters of more slippery duck and human interest, and tell a story which moves from facts on the duck fossil record, problems of taxonomy, habitat, feeding and migration, to the border territories of navigation, sociability, display and sexual behaviours.

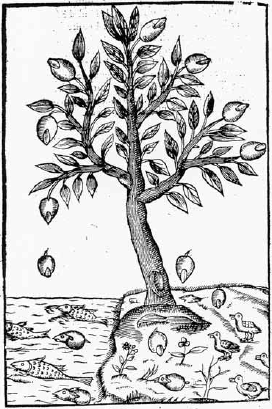

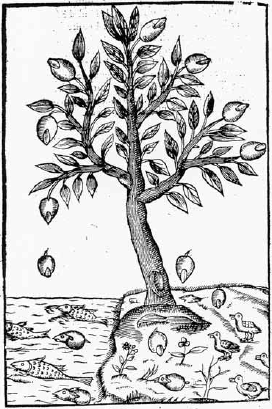

| Durets depiction of a tree from which fish or fowl are made, depending on where they fall. |

Chapter Two examines wild duck hunting, domestication, and how ducks continue to be pressed into social organization. Chapter Three analyses associative human and duck sound and resulting metaphor and music. The discussion of a politicized relationship between ducks and humans is animated by Disneys Donald in chapter Four, while chapter Five explores duck shapes and entertainment. Chapter Six brings the book to a close with a review of ducks and doctors, ducks and disease, and ducks and meaning.

In a Mexican creation myth a great bird came whirling, and its feathers fell into the water, turning into all the waterbirds of the world. Duck came from one of those feathers. Another tale relates how the Iroquois hero Hiawatha, travelling through Mohawk territory, came to the edge of a great lake. As he was wondering how to cross it, a huge flock of ducks descended on the lake and began to drink the water. When the ducks rose up again, the lake was dry, its bed covered in shells. From these shells Hiawatha made the first wampum beads and used them to unite the tribes in peace.