30-SECOND

ANATOMY

The 50 most important structures and systems in the human body, each explained in half a minute

Editor

Gabrielle M. Finn

Contributors

Judith Barbaro-Brown

Jo Bishop

Andrew Chaytor

Gabrielle M. Finn

December S. K. Ikah

Marina Sawdon

Claire France Smith

Published in the UK in 2011 by

Ivy Press

210 High Street, Lewes,

East Sussex BN7 2NS, U.K.

www.ivypress.co.uk

Copyright The Ivy Press Limited 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage-and-retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright holder.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-78240-071-4

Ivy Press

This book was conceived, designed and produced by Ivy Press

Creative Director Peter Bridgewater

Publisher Jason Hook

Editorial Director Caroline Earle

Art Director Michael Whitehead

Designer Ginny Zeal

Illustrator Ivan Hissey

Profiles Text Viv Croot

Glossaries Text Charles Phillips

Project Editor Jamie Pumfrey

Typeset in Section

Printed in China

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Distributed worldwide (except North America) by Thames & Hudson Ltd., 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX, United Kingdom

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Gabrielle M. Finn

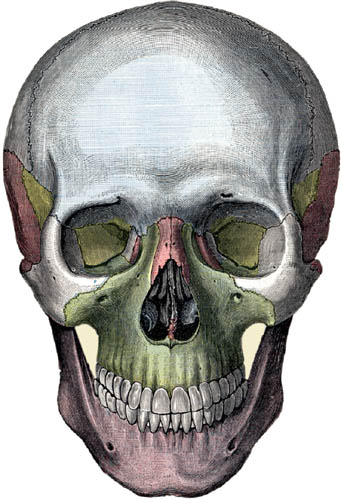

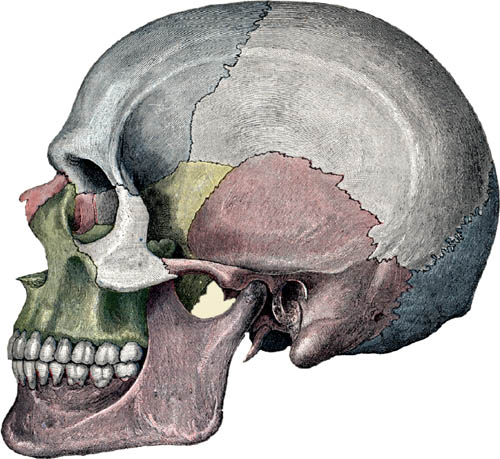

Anatomy is both within and all around us. By learning a little anatomy, we come to understand how our bodies are built: An anatomical drawing that depicts the bones, muscles, ligaments, tendons and organs of the body is a map of the inner landscape we all share. Yet at the same time, our experience of the body, our knowledge of its skeleton and organs, informs the way we see the world. For this reason, human anatomy has a widespread symbolism in popular culture, from the hearts printed on Valentines Day cards to the skull as a symbol of danger.

Gruesome history

Traditionally, many people may have seen anatomy as an academic discipline, of interest to only medical students, but in recent years the subject has had a boom in popularity. This is due largely to its entry into the public arena through touring exhibitions of cadaveric specimens and televised human dissections by anatomists, such as Gunther von Hagens and Alice Roberts. Behind this new interest lies a long and gruesome history.

The origins of anatomical study were in animal vivisection and the dissection of human corpses. The ancient Greek physician Galen based his ideas of human anatomy on knowledge gained from dissections and vivisections of pigs and primates. The Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci, creator of The Last Supper and the Mona Lisa, was famed for his anatomical drawings and derived his knowledge of the inside of the human body from working with corpses supplied by doctors in hospitals in Milan and Florence. Anatomy has also been associated with crime, as in the case of the nineteenth-century murders perpetrated in Scotland by William Burke and William Hare. A pair of Irish immigrants, they robbed graves and embarked on a serial-killing spree in 182728 in order to sell corpses to Dr Robert Knox, an anatomy lecturer with students from Edinburgh University medical school. The pair were caught: Hare was granted immunity for testifying, and Burke was hanged on 28 January 1829; ironically, his remains ended up in the medical schools anatomy museum.

Anatomical blueprint

Despite the fact that anatomy describes the blueprint for the living body, one of the subjects most common associations is death the bones that structure our living bodies are our final physical remains.

Evolution and variation

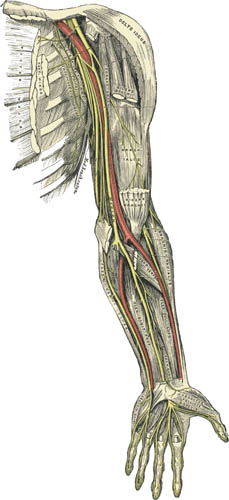

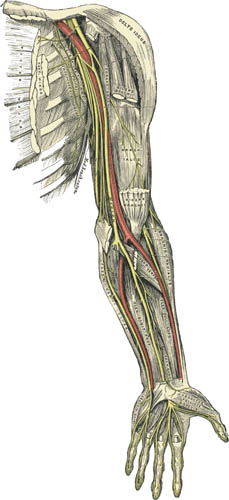

Anatomy is an ancient discipline, and you might think that there is nothing new to know in the field. Yet, remarkably, human anatomy continues to evolve. This evolution is very slow, but it exists and persists. Take, for example, the coccygeal bones at the base of the spine: These used to be the point at which the human tail started. Another example of continual evolution is the palmaris longus muscle in the forearm; due to its limited function, this muscle has become redundant, and evolution in some individuals has resulted in its absence in around 15 per cent of people.

One of the biggest challenges facing anyone who wants to study anatomy is anatomical variation. As we have seen, anatomy provides a blueprint for how all bodies are structured; however, in a world with a population heading for an estimated 7 billion people, variation will and does exist. A primary example is found in the arteries within the pelvis; there are fifty-four known variations of how these vessels distribute themselves. Moreover, variation exists not only from person to person, but also from side to side within an individual body. Some people have a larger ear on the right than on the left; or a person may have a single horseshoe-shaped kidney instead of the normal two kidneys; or the pathways followed by nerves may vary from the accepted convention. This book presents the most commonly encountered anatomy.

Anatomy systems and functions

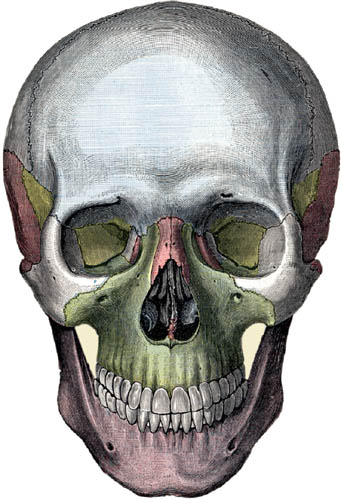

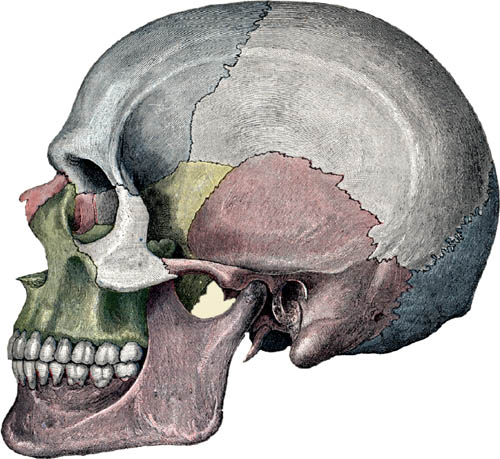

Anatomy has its own technical language, in which muscles and bones have lengthy Latin or Greek names. Simple physical actions, such as the movement of the lower limb (leg), have multiple anatomical descriptions depending on the direction of the movement. There are in excess of 200 bones, 600 muscles and numerous veins, arteries and nerves. Dont let that put you off. This book does not attempt to explain the location and function of each individual structure; instead, it breaks the body down into functional systems and describes the fifty most relevant components, using illustrations and avoiding complex terminology.

Another consideration is that anatomical structures whether a single muscle in the thigh or a digestive organ, such as the stomach do not work alone. Although the text maps out individualized functions for each structure, the reality is that everything works together. The function of one organ might rely on a hormone produced by another, or the movement at a joint may result from the actions of three or four muscles working together. Think about the bigger picture.

Medical pioneers

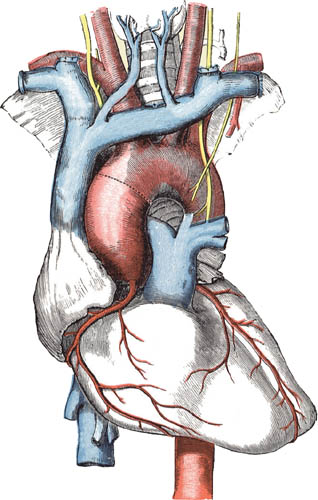

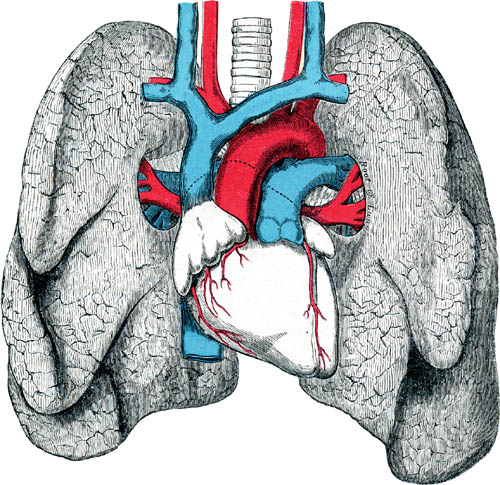

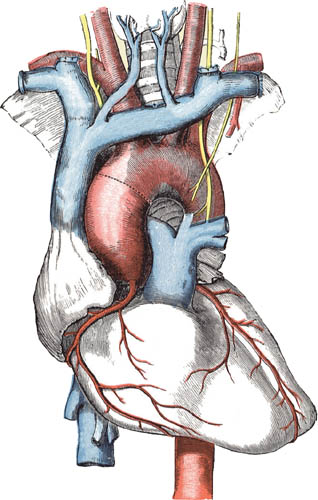

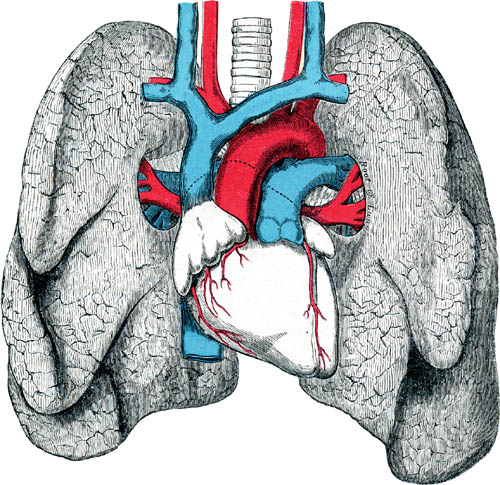

Great breakthroughs in anatomy have often taken the form of correcting earlier errors. The Englishman William Harvey (15781625) featured on was the first to establish the true role in the body of the heart (top) and lungs (below)

Next page