Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gurstelle, William.

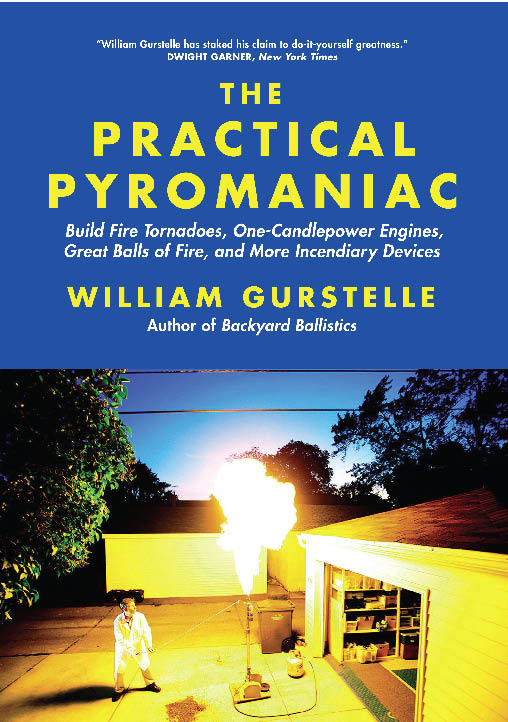

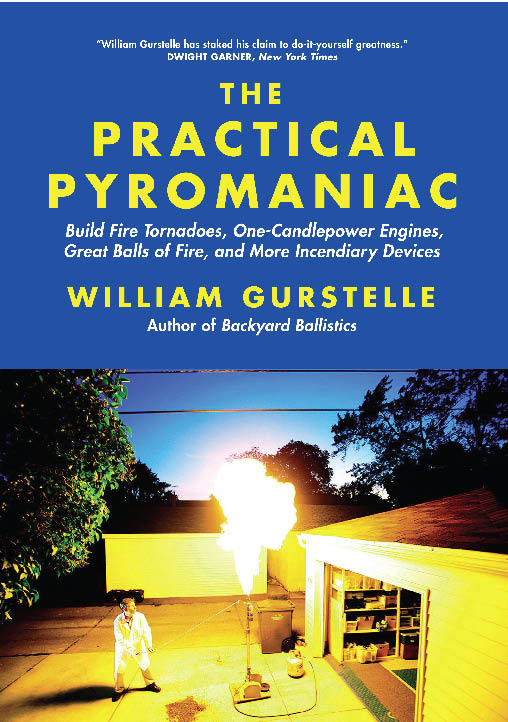

The practical pyromaniac : build fire tornadoes, one-candlepower engines, great balls of fire, and more incendiary devices / William Gurstelle. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56976-710-8 (pbk.)

1. Fire. 2. Combustion, Theory of. I. Title.

TP265.G87 2011

541'.361dc22

2010053910

The author and the publisher of this book disclaim all liability incurred in

connection with the use of the information contained in this book.

Questions? Comments? Visit www.ThePracticalPyromaniac.com

Follow the Practical Pyromaniac:

www.facebook.com/PracPyro

www.twitter.com/PracPyro

Cover design: John Yates at Stealworks.com

Cover photo: David Howells

Interior design: Scott Rattray

Interior illustrations: Todd Petersen

Copyright 2011 by William Gurstelle

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-56976-710-8

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5

Dedicatory Clerihew

The Hansen family

Is known for their hospitality,

Without being specific,

In all ways theyre terrific.

Contents

Introduction

1 Keeping Safety in Mind

2 The Flame Tube

3 The First Lights

4 The One-Candlepower Engine

5 The Fire Drill

6 The Burning Ring of Fire

7 The Hydrogen Generator and the Oxygenizer

8 Exploding Bubbles

9 The Fire Piston

10 The Arc Light

11 Fireproof Cloth and Cold Fire

12 The Extincteur

13 The Photometer

14 Thermocouples

15 Technicolor Flames

16 The Fire Tornado

17 Great Balls of Fire

Epilogue

Bibliography

Introduction

The Paradox of Fire

Fire is the most important agent of change on earth. It makes our cars and airplanes move, it purifies metals, it cooks our food. It also destroys forests and pollutes the atmosphere. Fire is also one of the most paradoxical forces in nature. Sometimes its incredibly difficult to light a much-desired campfire and keep it going, while at other times unwanted fires start far too easily.

To Greek philosophers of the Classical era, fire was a tangible, material thing. The legends they repeated held that noble Prometheus purloined fire from Mount Olympus and secretly gave it to human beings, much to the chagrin of an angry Zeus.

As Greek civilization progressed, legends became insufficient; people sought to understand fire on a more scientific basis. The first major nonmythological theorist was the Greek scholar Empedocles, who devised the earliest well-known explanation of the nature of the world. Everything, he said, was made up of four elements: earth, air, water, and fire. This was called the Four Element hypothesis. Aristotle refined that a bit, and for the next 2,000 years it was accepted with only minor modifications as the cosmological basis for the entire universe.

The hypothesis stated that everything in the world is composed of these four elements; the only difference between all the things we see or touch is the relative abundance of the four constituent components. Wood, according to Aristotle, is a composition of earth and fire, as evidenced by the way wood burns. Nonburning rock is mostly earth, with perhaps a bit of water added.

In the Middle Ages, this explanation no longer fit the results of many experiments that involved fire. Many alchemists had excellent experimental technique and analyzed a number of chemical processes in their quest to turn base metals into gold. But when fire was involved, their experiments yielded results that didnt jibe with the classical Four Element worldview. The pillars of cosmological doctrine were crumbling away. The alchemists were beginning to suspect that the world was more complex than they had been taught.

In the 1700s, a new way of thinking called phlogiston (flo-jis-ton) theory came into fashion. This theory, which was promoted by many of the leading scholars of the age, held that fire was caused by the liberation of an undetectable chemical substancephlogistonwhich was bound up inside all things that could be made to burn. Those items that possessed phlogiston ignited and combusted; those without it did not. Phlogiston theory made sense for a while. But like the Greek notion of matter, phlogiston was merely an expedient, a theory cobbled together to describe the things that even close observations of the world could not otherwise explain.

At the end of the 18th century, improvements in experimental technique combined with the astute observations of a new generation of enlightened thinkers led to a much better understanding of the world in general and science in particular. It started with important discoveries by Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford; Joseph Priestley; and Henry Cavendish. The work they did laying the foundations of modern chemistry was built upon by others, notably John Dalton and Antoine Lavoisier, until a new and correct interpretation of the phenomenon of fire emerged. At the turn of the 19th century, scientists were finally beginning to truly comprehend fire.

At that time there was a lively, collegial, and incredibly productive community of scientists fascinated by fire. During a fairly short window of time, a few years on either side of the year 1800 and centered around the Royal Institution in London, a surprisingly small but interconnected community of scientists solved the mysteries and banished the superstitions surrounding fire, finally allowing scientific understanding to take hold.

It was not a direct path. There was plenty of meandering and zigzagging through half-correct theoretical deductions and unexpected laboratory results. But eventually, a body of true and practical knowledge was accumulated. It was these turn-of-the-19th-century natural philosophers (the word scientist was not coined until the 1830s) who paved the way for modern scientists to understand the true nature of fire.

Isaac Watts was one of the key contributors to the advancement of preIndustrial Revolution science, but he wasnt a scientist. He was a 17th-century English logician and musician, best known as a composer of Christian hymns. (His most famous work is Joy to the World.) More than that, he was an important theorist on the nature of learning, a father of scientific and logical pedagogy. His influence on the scientists and experimenters who appear in these pages was immense.

Watts shared his philosophy on understanding the world in several highly regarded books, his most famous being The Improvement of the Mind . Written in 1815 toward the end of his life, it had tremendous influence on generations of students and teachers. It is still in print and popular even now, 200 years after Watts wrote it.

Wattss books were standard issue to generations of Oxford and Cambridge University students. His ideas served as one of the foundations for learning logical thought, shaping European society for more than a hundred years. Many suggestions for bettering oneself flow through the pages of Wattss books. Foremost among them, Watts urged his readers to improve their minds in five different ways, which he called his five pillars of learning. Through the technique of the five pillars, Watts hoped to improve the lot of the world.

There are five eminent means or methods whereby the mind is improved in the knowledge of things, and these are: observation, reading, instruction by lectures, conversation, and meditation.

Next page