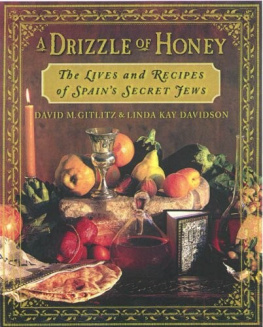

David M. Gitlitz - A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spains Secret Jews

Here you can read online David M. Gitlitz - A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spains Secret Jews full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2000, publisher: St. Martins Publishing Group, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spains Secret Jews

- Author:

- Publisher:St. Martins Publishing Group

- Genre:

- Year:2000

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spains Secret Jews: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spains Secret Jews" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spains Secret Jews — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spains Secret Jews" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Ruth Kaletsky Gitlitz

and

Helen Scott Davidson,

in whose kitchens

we learned so much

While we take full responsibility for errors, omissions, and culinary oddities, we thank several people who contributed to the books completion: Andree Brooks, for her encouragement; Jeanne Fredericks, for believing in the project; Constance Hieatt, for taking time to read a portion of the manuscript and giving important historical data; Susan Offer, for critically reading portions of the manuscript and adding valuable suggestions; Charles Perry, for sharing his knowledge about Arabic medieval cooking; and the librarians of the University of Rhode Island, who helped us track down rare material. Our thanks to Elma Dassbach, Julie A. Evans, Michelle LaRoche, and David Riceman, for data that they shared with us; and Abby and Deborah Gitlitz, whose helping hands and good ideas lightened our work in the kitchen. We especially want to thank Jennifer Weis and Kristen Macnamara at St. Martins Press, for shepherding the manuscript through the publication process, and our copy editor, Estelle Laurence, for her meticulous attention to detail. Lastly, we appreciate family, friends, and students who have braved the experiments of our kitchen and whose critical palates have helped us refine these dishes.

Beatriz, Nunez was arrested by the Spanish Inquisition in the spring of 1485. She and her husband, Fernan Gonzalez Escribano, had converted from Judaism to Christianity a few years earlier, but Beatriz still kept a kosher home. One of their maids, Catalina Sanchez, was a witness for the prosecution. Among the particulars of the familys Jewish practices that she denounced to the Tribunal was a recipe for a Sabbath stew made of lamb and chickpeas and hard-boiled eggs. The Guadalupe Inquisition found Beatriz guilty of being an unrepentant heretic and burned her alive in 1485.

Beatriz Nezs Sabbath stew is one of approximately ninety detailed references to Jewish cooking in Iberia and the Iberian colonies that David Gitlitz found during two decades of reading Inquisition testimony. These recipes bring to life an important part of the daily routine of the converso residents in the Iberian Peninsula and its colonies some five hundred years ago. They also vividly demonstrate how the Inquisition used cultural information to help build a case against those it was investigating for heresy.

The documentary references to foods, rarely more than a list of main ingredients, point to a varied cuisine enriched by many flavorings, sometimes named and sometimes only alluded to. The ninety recipes include dishes in traditional food categories such as snacks, salads, stews, vegetables, fish, and desserts. Several recipes describe special holiday foods for Passover and for breaking the Yom Kippur and Purim fasts. Most are from Spain in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. A few are from Portugal and a few come from the American colonies of Mexico and Brazil in the seventeenth century.

For two years we have experimented with these embryonic recipes in our kitchen to make them accessible to modern cooks. Remembering that most of the historical references come from the time just before Christopher Columbus and the conquistadores brought New World products back to Europe, we put away the American staples such as tomatoes, corn, bananas, potatoes, and chile peppers. In return, we renewed our acquaintance with some of the tasty Old World standards like turnips, parsnips, and quince. We went through the pantry and excluded those spices that were available only after the sixteenth century (such as allspice and paprika); in their place we could experiment with now-ignored spices that were highly prized in medieval Europe (galingale and grains of paradise, for example). To contextualize our work, we pored over medieval cookbooks and modern studies of medieval cuisine.

What surprises anyone in his or her first contact with medieval cooking is the rich variety of edible materials. The main foods mentioned in these recipes are almost all still used today worldwide. But during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, some were specific to the Iberian Peninsula, others limited to certain areas of the Peninsula. The now-ubiquitous eggplant, for example, was brought to Europe through the Peninsula, and was hardly known outside of Iberia until perhaps as late as the seventeenth century. In thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Iberian cookbooks, it is often associated with the Muslims and Jews living on the Peninsula. The chickpea is a very common ingredient in the converso Sabbath stews; but contemporary Peninsula cookbooks of the well-to-do households rarely call for it, and a thirteenth-century Arabic cookbook states that it is eaten only by the poor. Salad was not limited to just lettuce, but embraced a dozen or more garden crops, including lavender, rue, and portulaca, which were topped off with anything else at hand.

The same abundance holds true for herbs and spices. Where a twentieth-century cook might prefer to emphasize one specific taste in a dish, using a limited number of aromatic ingredients, medieval cooks believed in the dictum more is more. It is not unusual to have eight to ten seasonings in a single dish. Popular legend would have it that spices were too expensive to be much in evidence in the cooking pot. Not so. Many spices may have been costly, but they were highly sought after and recipe books call for their use continuously. Some standards, like pepper, continue to be standard in the modern kitchen. Other often-used spices, such as cassia and cardamom, are used more reservedly now.

Also noteworthy is the sweet tooth in Europe at that time. Both sugar and honey were popular sweeteners, added to dishes or even eaten alone. The document reproduced on the frontispiece records how Juan de Len, in prison in Mexico in 1646, asked his jailers to bring him two dishes of honey, with which he intended to break his fast. A drizzle of honey or a sprinkling of sugar over a dish often added a finishing touch. In some parts of the Iberian Peninsula, a cinnamon-sugar topping was not limited to bread. It was sprinkled, liberally, over vegetable, egg, and meat dishes, even the dish with ten other seasonings. And then it was likely to be followed by a drizzle of rose or orange water over everything.

We want to make clear that the recipes offered in this book lay no claim to being precisely those dishes that the informants set on their tables in Castile or Portugal during Inquisition times. At best the historical documents have hintedby recipe name, by list of principal ingredients, or by contextat the nature of the dish enjoyed by a particular Jewish or crypto-Jewish family at a particular time. We have taken these clues and carefully contextualized them in the world of late medieval Iberian cooking, a world which has proved notoriously imprecise with respect to measurements, methods of preparation, or even the nature of specific sauces or combinations of spices. Within the constraints of the medieval Iberian kitchen, we have experimented quite freely along all of these dimensions, and as a result we have often produced two or three versions of a given dish. Frequently we suggestin the Variations section of the recipeslines of experimentation which you, too, might follow. If you are new to medieval cooking, see the chapter titled Cooking Medieval in a Modern Kitchen for some basic information about approximating medieval ingredients in the modern kitchen.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spains Secret Jews»

Look at similar books to A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spains Secret Jews. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spains Secret Jews and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.