The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

To my father

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the many Florentinesalong the walks and inside shops, restaurants, banks, churches, and librarieswho have helped me with information, anecdotes, and access to corners of the city seldom seen by the passerby. In particular, I am grateful to Barbara and Bill Larson for always keeping a key under the mat for me, to Catherine and Tim Larson for pointing out to me what children like to do and see in Florence, to Sandra Celli, Polly and Carlo Colella, and to Anna Nathanson.

On the other side of the ocean, I wish to thank Professor Gene Brucker of the University of California at Berkeley and Professor Brenda Preyer of the University of Texas at Austin for their invaluable research suggestions. For starting me off in the right direction I thank Judith Haber, and for help along the way, Charles Kaiser and Bernard Alter.

Im especially grateful to Marc Granetz, the editor of this book, for suggesting the idea of Florencewalks to me and for polishing my often cloudy prose.

Finally, I would like to thank Daniel for his patience, translating abilities, good humor, and for being not only an excellent photographer but also the best traveling companion inside or out of Florence.

Introduction

A friend of mine once said to me, Visiting Florence is like calling at your great-aunts house. You walk around very carefully because youre afraid of knocking over and breaking something precious.

Over the centuries, the image of Florence as precious has developed a patina as polished as a priceless bronze. The Renaissance is heralded as an era of unparalleled achievements in art, architecture, and science, and Florence was the magic city in which these marvels were born. One is supposed to visit Florence with a cultivated eye and with awe for good taste, the fine arts, and ecclesiastical grace.

But in reality Florence is not as delicate or demure as most travel brochures and coffee-table books might lead us to think. The city has a vivid, volatile historyChristian martyrs thrown to lions, neighborhood clans engaged in bloody vendettas in the streets, poorly paid wool-workers rioting in the marketplaces until their voices were heard in the powerful guild halls.

Florence is a dollhouse setting for much of the theater of Italian social historyin fact, for much of the social history of the Western World. In the first two centuries before Christ, Florence (or Florentia) was little more than a factory town and Roman port. Iron making was probably the chief industry. Ore that was extracted on the island of Elba and shipped up to Pisa was brought down along the wide stretch of the Arno to Florentia.

Overlooking the port and its activities was the Etruscan town of Fiesole. The Etruscans were a proud group of people who traced their ancestors back to Asian nomads and Sandon, the king of Babylonia. When and how they settled in Italy are unresolved matters, but at some time a delegation from southern Lydia in Asia Minor may have been responsible for introducing Greek art and culture into their lives. Depictions of Hercules, equipped with his bow and metal mace, have been found in Etruscan tombs, and his lion is still part of the emblem of Florence today.

Fiesole was captured by Roman armies in the second century B.C. Three concentric walls were built around the hilltop, and a fourth wall extended down to Florentia and the Arno. The entrances to this enormous citadel were along the rivers edge. Three gates, spaced a mile apart, were the only access to the occupied town. The Roman general Sulla parceled out tracts of Florentia to members of his twenty-three legions. The soldiers, in turn, showed their allegiance to the mother city, Rome, by building a miniature copy complete with a Field of Mars, a Forum, a Temple of Mars, baths, a theater, an amphitheater, and an aqueduct.

Fiesole, meanwhile, played a very different role. The town became the center of soothsaying in the Roman world. Long known for its skilled body of priests trained in the rites of sacrifice and divination, Fiesole annually welcomed twelve Roman youths who were sent to the hillside temples to study augury. In the first century A.D. , Pliny remembers the auspicious sight of a Fiesolan entering the gates of Rome accompanied by his seventy-four sons and grandsons and a commission to carry out some serious soothsaying.

In the same century, Christian converts began to invade Florentia. The Christians were persecutedthrown to lions in the amphitheateron and off throughout the third century A.D. But by 313 a bishop was living safely in Florence; its likely that the first Christian cathedral was built around this time too. The Church of San Salvador was the name of the edifice, and its location was quite near if not directly under what is now the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in the Piazza del Duomo. Sandwiched between the first cathedral and the last was Santa Reparata, a church named for a twelve-year-old female martyr. The young saint was said to have appeared in the middle of a fifth-century battle between a host of Vandals and Goths and the citizens of Fiesole. Santa Reparata suddenly arrived on the spot with a bloodred banner and a lily in her hand. Miraculously, following close behind her was the Roman general Stilicho with a fresh legion of troops. The barbarians fought a losing battle, and the Florentines built a new cathedral in remembrance of the girls military assistance.

Money-making, church-building, and nobility-feuding were the activities of primary importance in the newly cosmopolitan Florence of the thirteenth century. Frescoes, paintings, statues, murals, and tapestries were the artistic accessories to a world that was waking up to self-expression, creativity, vanity, materialism, and physical adornment.

Art masterpieces and Florence are synonymous. On my twenty-first birthday I made my first pilgrimage to the shrines of Michelangelo, Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, and Giotto. As an art student, I spent the obligatory hours in the Uffizi Gallery, the Pitti Palace, the Convent of San Marco, and the Accademia delle Belle Arti. Over the years, as Ive visited family and friends in Florence with new personal interest in archaeology, urban planning, and architecture, I have continually seen the city from new perspectives. I have come to understand how the great artworks, the churches, the palaces, the commercial life, and the very shape and pattern of the city were all products of an extraordinary group of men and women who have lived and earned a living here.

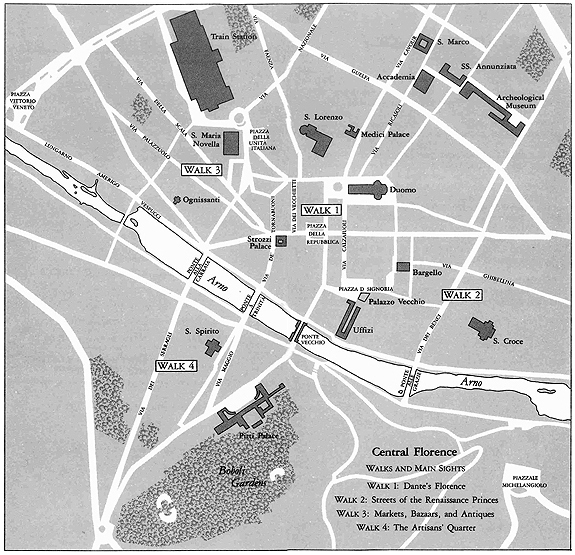

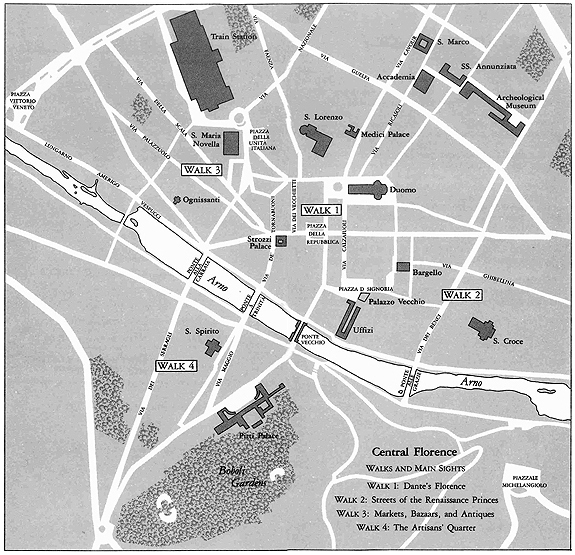

The four walks in this book were chosen with this large perspective in mind. After strolling around the streets of Florence your impression of the town and its masterpieces may change greatly. You may begin to reflect on the history of this unique city and of the peopleChristian saints and martyrs, Saxon princes, French usurpers, English expatriateswho have flocked here. The first walk centers on the very core of Florences history: the Old Market, guild halls, medieval towers, and crooked alleyways where Dante used to roam. Some of the highlights of the second walka doll hospital, the site of the ancient lions dens, a top-notch ice-cream salon, some fishermen and perhaps a boat race on the Arnomake it (even in an abbreviated form) especially appealing to children. The third walk winds around thirteenth- and fourteenth-century buildings, open-air markets, and elegant, inviting shops of all varieties. The fourth walk on the other bank of the Arno takes in the oldest woodworking district in Florence, some famous frescoes that Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo used to study, and one of the few streets in the city that still looks exactly as it did at the height of the Renaissance.