My mother went to school when she was seven. Her entire school about fifty students was taught in a single room. One section of the room was Class One, another section was Class Two, and so on. She didnt have writing paper or a book or a pencil. She broke her brothers pencil in half, then ripped off half his writing paper so she had some paper and a pencil to write with. When she was sixteen, she met my father through an arranged marriage.

My mother went to school when she was seven. Her entire school about fifty students was taught in a single room. One section of the room was Class One, another section was Class Two, and so on. She didnt have writing paper or a book or a pencil. She broke her brothers pencil in half, then ripped off half his writing paper so she had some paper and a pencil to write with. When she was sixteen, she met my father through an arranged marriage.

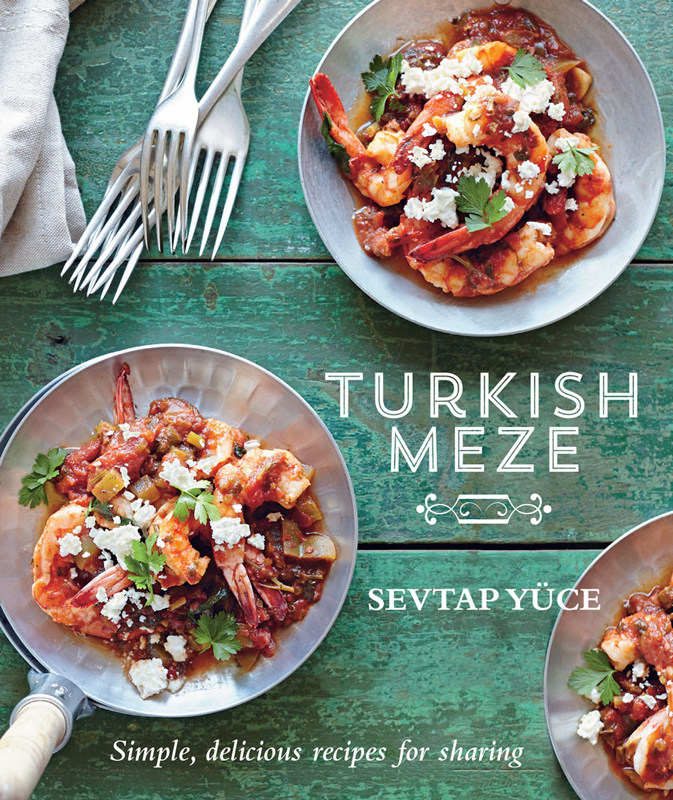

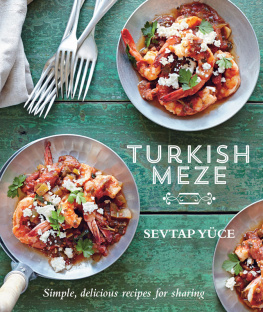

They were married, and this was when my mother made her first meze. It was for my father. In time her brother, Ibrahim Catma, became my fathers best friend, and my favourite uncle. In those days meze was only for the men. They would sit at the table and the women would prepare the food. To start, they might nibble on a bowl of salted pistachios, or fresh green almonds and a little bowl of salt.

They would dip the almonds into the salt and take a little bite, then have a sip of raki. The bottle of raki would sit in the centre of the table with a jug of water. Each man had two glasses in front of him. One glass would have two fingers of raki, the other glass would be full of water. The glass of raki would then be topped with fresh water, turning the clear raki cloudy, into what we called lions milk. As a child I was mesmerised watching the men turn two clear liquids into a cloudy nectar.

Then they would raise their glasses and touch their hands together and say Can Cana (pronounced Jan Jana), meaning Life to Life. If they were just friends they would say Serefe, meaning To your honour. Next the chunks of watermelon and feta would arrive, with slices of beautiful honeydew melon, crunchy fingers of cucumber, delicious deep-red tomatoes and tender, sweet green baby capsicums (bell peppers). After this would come the dishes of food braised in olive oil. A sip of raki, a sip of water, and morsels of the meze. Meanwhile the men would be chatting away solving the worlds problems while the women prepared the next hot dish for the meze.

Nowadays we all sit together, men, women and children all now share the same experience that our fathers and uncles and grandfathers shared. Now we are part of the whole experience, but you only make meze for your loved ones those you wish to spend many, many hours with. Meze is always a seasonal affair. Each region would have its own distinctive meze, depending on the local produce of each season. Winter would bring fresh glossy anchovies, tossed in flour, fried briefly and served with a chunk of juicy lemon. In spring, thered be green beans, tomatoes and stuffed capsicums (bell peppers).

Music was always part of the experience. When I was a child, I watched the big black discs with a hole in the middle go round and round: vinyl records. If anyone could play an instrument, they would entertain us. Maybe someone would play the saz a traditional long-handled stringed instrument. Nowadays in Turkey you may go to a taverna or meyhane and the waiter will come to your table with trays of meze and you select the food your eyes are seduced by. Then you choose the main meal.

Everything is shared, every little dish, and always there is much discussion about each morsel. History tells us meze originated in Persia and spread throughout Turkey and beyond as the Ottoman Empire expanded. Today it is a way of living and eating, sharing all, including breakfast, lunch and dinner. For breakfast we drink tea, for lunch we drink ayran (a chilled yoghurt drink). As the sun goes down we drink raki or beer, or a glass of delicious wine. Times have changed! There are no rules with meze.

It is personal, it is seasonal, it is flexible it is the food that matches your choice of drink. Also, it depends how much time you have in your busy life. The meze could be dishes such as stuffed vine leaves or zucchini (courgette), stuffed tomatoes, fried sardines or anchovies, or perhaps a pure of broad beans (fava beans), or an eggplant (aubergine) salad. There will be many small dishes to follow the meze. My mother used to tell me a story about a sultan who had two sons. His favourite and elder son gave him all the gold and silver and treasures of the world, saying, I love you as much as all the treasures in the world.

The sultan replied, I love you, my son! The sultans younger son, however, told his father, I love you as much as all the grains of salt. The younger son then prepared a huge meze table for his father, using no salt in any of the dishes. The sultan tasted the food and declared, Son, there is no flavour in this food! To which his younger son replied, So, Father, now you know how I feel about you. This story taught me a lesson. I never put salt and pepper on my customers tables with my meze: I believe food brought to the table should have all the love and seasoning in it already. I came to Australia in 1985 as a child bride, at the age of sixteen, to marry the man arranged for me.

Years went by and a woman called Elea became one of my most beautiful friends. One night I wanted to cook dinner for her. What could I make for my friend? It had to be the most delicious meal in the world, but at the time I only had five dollars to spend. So I went to the greengrocer, then the supermarket, then the butcher. And then I went back to the vegie shop and bought some little bits of vegetables. Then I went back to the butcher and asked, Can I please get some chicken carcasses? How much will that be? He said, Nothing for the chicken carcasses for you, little one.

So I went home, put the carcasses in the biggest pot I could find and fried them in a little oil until golden. I washed and chopped my vegetables and added them to my pot. I topped it up with a bit of water and salt and pepper and cooked it until my vegetables were tender. A few minutes later Elea arrived with a bottle of Australian chardonnay and I have never looked back! She still loves my soup. When I was nineteen I met raki for the first time. It is the Turkish national drink, made with aniseed.

For the first few mouthfuls we got on quite well. But after a few more mouthfuls we had a massive fight. You can imagine who won. (It wasnt me.) I didnt know how to drink like my father or my loved ones: I was a raki virgin! Raki and I havent met since then. But, since every Turk thinks it is the lions milk, it might be different for you More years passed, and by the age of twenty-seven I had my own restaurant in Angourie, a small coastal town in northern New South Wales. Times were tough, winters were quiet so I began to arrange backgammon tournaments with meze platters for local families and new friends, and I was able to pay my bills.

Years later, I sit in my own home and think about my new Beachwood cafe, where people order everything off the menu, and how I carry out the sharing plates many times without even realising that I have created my own meze. My meze has always been in my blood. It is the way I love to eat, the way I love to entertain, the way I love to share my food. When I look back at my life in Australia, all my cafes have been based on meze, but I have never written this on my menu blackboard. Today, I serve my meze plates to people and watch the smiles on their beatiful faces. When I clear the plates, they are empty, with finger swipes on them, and that makes me smile.

Next page

My mother went to school when she was seven. Her entire school about fifty students was taught in a single room. One section of the room was Class One, another section was Class Two, and so on. She didnt have writing paper or a book or a pencil. She broke her brothers pencil in half, then ripped off half his writing paper so she had some paper and a pencil to write with. When she was sixteen, she met my father through an arranged marriage.

My mother went to school when she was seven. Her entire school about fifty students was taught in a single room. One section of the room was Class One, another section was Class Two, and so on. She didnt have writing paper or a book or a pencil. She broke her brothers pencil in half, then ripped off half his writing paper so she had some paper and a pencil to write with. When she was sixteen, she met my father through an arranged marriage.