One of my earliest childhood memories is lying in bed at night and hearing my mother yell into the phone, Mumdont forget to hang up the phone! More yelling, and then eventually the sound of my mother placing the receiver down, followed by a deep grumbling that only pure frustration can conjure. Shortly afterwards, Dad would enter the bedroom I shared with my sister, scoop us out of bed and bundle us into the car for a late-night drive to the Melbourne suburb of Collingwood. We would lie in the back of the family wagon (and when I say lie, I literally mean lie; no seatbelts were required back then, so my sister and I would lie top-to-tail across the back seat)and, after a fifteen-minute drive, Dad would announce our arrival into the spotting zone. We werent going to my nans house to deal with phone-gate. Nan didnt have a telephone so would use various public phone booths around her neighbourhood to keep in touch. Which one she used on any particular day or night was anyones guess. My sister and I would try to keep our overtired eyelids open enough to locate the one dimly lit phone booth with the swinging handset somewhere within Nanas neighbourhood, motivated by the prize of a Caramello Koala chocolate for the first one to spot it.

Back in those days, if someone phoned you landline to landline and didnt hang up at their end, your phone was rendered useless until their receiver was placed properly back in its cradleotherwise the call was still effectively active. We would often hear Mum pick up the phone, only to start yelling into the receiver the name of the person she last spoke to. Usually it was Nana.

It wasnt as if Nana meant to cause such an upheaval every time she rang late at nightin fact, Nana probably didnt even remember she had called at all by the time she walked back through her front door.

Nana had Alzheimers.

The phone calls didnt always end in a late-night family expedition to locate and replace the dangling handset. Sometimes Nana would call to say the power in her house had gone out and none of her lights were working. These calls usually resulted in Dad flying solo; the phone-booth journey required a driver and a spotter, hence the family excursion. It was always a case of Nana having not turned the lights on, and I found it so peculiar that she didnt know how to turn the lights on and off on her own.

Then wed get calls from her neighbours and friends informing us of Nanas latest adventures. The lady who lived next door would call and simply say, Mrs Pitts gone shopping. Sounds innocent enough, except those calls would always come between the hours of 1 a.m. and 4 a.m. I still have visions of Nana tottering into town in her dressing gownbuttoned unevenly, of coursehandbag clenched firmly under her arm, stopping only to check, every block or so, under the guidance of a flickering street lamp, that she had the house keys.

In the early days, Nana would catch the tram to our house every Saturday morning and spend the day; if Mum and Dad were heading out to the local dinner dance later that evening, she would stay the night and look after us kids. I must have been about six or seven when I noticed she was acting weird. My sister was four years older than me, and my brother, being ten years older, was probably not around as much. He had little tolerance for Nanas shortcomings: she was a big part of our lives, and my brother had obviously witnessed firsthand the decline in her mental statebut all I ever knew was a nana who was a bit different. Much of the time spent at our house would involve her wandering around asking if anyone had seen her keys. They were always in her bagjust where they were last time she checked. My brother was so annoyed one afternoon that he got some ribbon, threaded her keys onto it and hung it around her neck! I guess the frustration of such adverse behaviour in our loved ones can drive us to the edge. I remember it used to make me laugh. To me, as an innocent kid, Nana was hilarious.

Forty years ago, many older people, rather than being diagnosed as having Alzheimers or dementia, were simply considered senile. And to be fair, the older generation were living in a swiftly changing world, in which technology was progressing at a rapid rate. Even small changes such as circular dials on phones changing to push buttons were advances people like my nana had to get their already muddled heads around. The decimal system had also changed from pounds and shillings to dollars and cents, so paying the conductor for her tram ride required a little extra mental power. When your brain is also starting to decline, life can become very confusing!

Nana had to manually light her gas fireplace with a match, and the carpet in front of it had several burn marks where she would just drop the lit match. She started leaving the gas stove on, so my cousin would call in on her way home from work each night and take the knobs off the stove, just in case Nana decided to whip up a little midnight snack and leave the gas running; my uncle would stop by each morning on his way to work and put the knobs back on. As her dementia worsened, Nana would spend all day wandering around the city and arrive back home around 5 p.m. A little sit down on the couch to rest would result in a two-hour nap. During daylight saving, it was still light when she woke around 7 p.m., so Nana would think she had slept all night and totter off into town for the day, only to find it all dark and deserted by the time she got there. More confusion.

My mum, unlike her sister, had a drivers licence, so she was the one called upon when anything went wrong with Nana. When all of this was going on, Mum was about the same age as I am now. I have no idea how she coped with the constant worry and disruptionstrying to look after three kids, with my dad often away through the week working.

It should have been enough to drive her crazy.

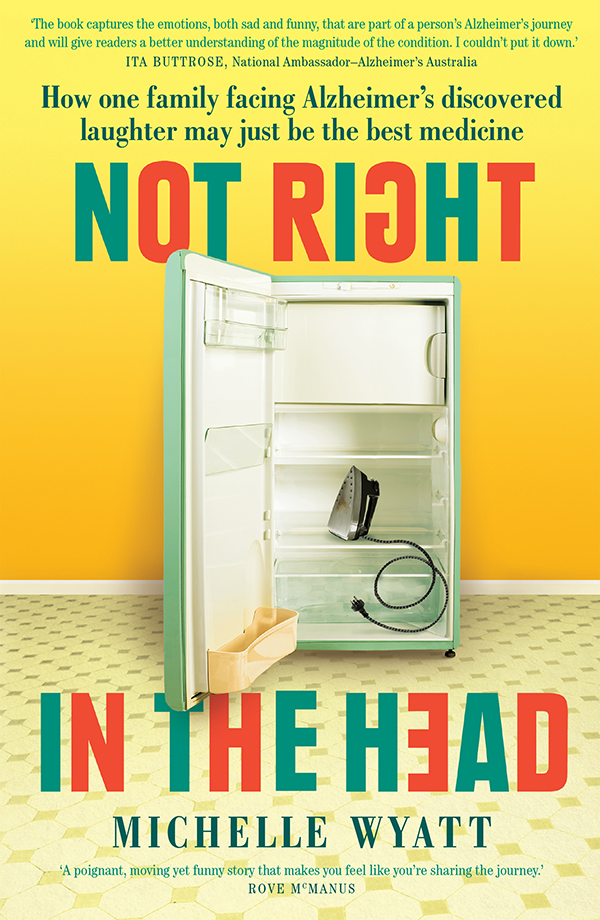

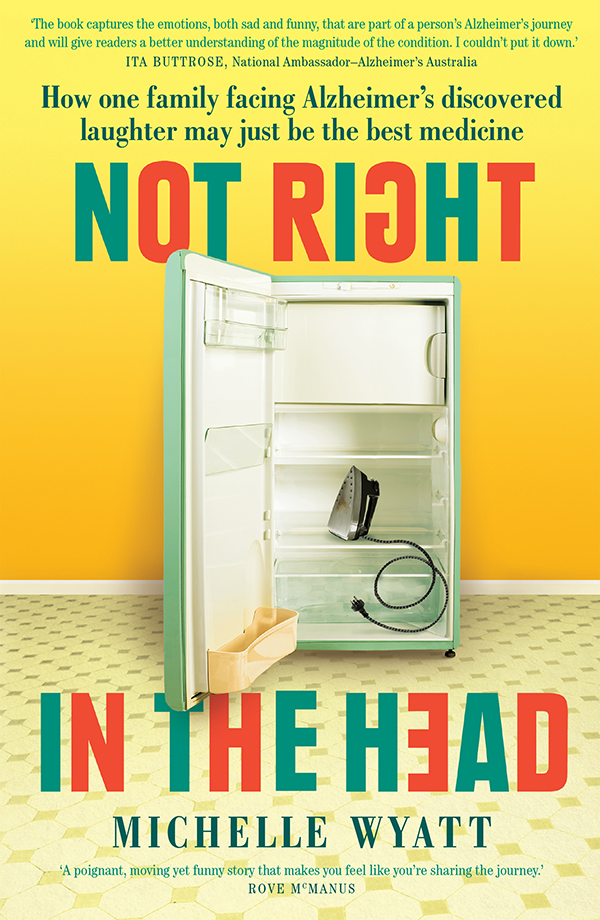

Maybe thats exactly what it did.

Alzheimers is a tough topic to write about with any kind of light-heartedness, so I have tried to get the balance right. This is not a self-help book, nor is it a medical guide, unless my Dr Google skills are valid enough to earn me the letters MD at the end of my name. Instead, throughout this book, I share stories of my own familys experiences, and also the stories of others who have lived through this disease. I also try to offer a general understanding of the disease, its possible symptoms, and how it progresses. My lawyers probably want me to say something here like, This book does not endorse any therapy or drug use in the prevention or treatment of Alzheimersand I agree, I endorse nothing (unless I am offered copious amounts of money to do so and even then the lawyers would put the kybosh on it). At the end of the book youll find a list of helpful Alzheimers organisations and websites, if you feel the need for more information and support.

I guess the main catalyst for writing this book was a desire to share my familys personal story, but also to reassure people who are caring for a loved one with Alzheimers that they are not alone, and that others are going through very similar scenarios. I still grieve daily for the loss of my beautiful mother, and I see my fathers constant struggle to continue on without her. But as a family we got through itand what ultimately did get us through was allowing ourselves to smile and laugh occasionally at some of the unusual and challenging circumstances that arise when caring for someone with Alzheimers.

Im not suggesting for a moment that, for anyone who has a loved one living with Alzheimers or dementia, life is a walk in the park and a reason for laughtereven to this day I find it heartbreaking to see what this disease does to people. I dont laugh at the disease or anyone who has it, but when you are confronted with something so challenging that pushes your comfort levels, its important to find something to help you deal with itand to quote a clich, sometimes laughter can be the best medicine.

Next page