It is ten years since research for this book began. The original objective was a masters thesis in history which was completed eight years ago. Since then the material has been reworked, and greatly expanded, to appeal to the general reader as well as genealogists and historians.

During the decade-long gestation a great many people have contributed in many different ways, often without knowing it. They include the librarians and archivists who helped me to delve into the treasure troves of nineteenth-century shipboard diaries and official documents kept at different places around the country: the Auckland City Library, the Auckland War Memorial Museum, the Alexander Turnbull Library, Archives New Zealand, Canterbury Museum and the Hocken at Otago University.

Some of them also provided invaluable assistance in tracking down images of life on the ships in the 1870s and 1880s, as did the staff of the Illustrated London News picture library.

Late in the process of producing the book the descendants of a number of people who made the long and perilous voyage also gave invaluable assistance by providing pictures of their ancestors: Rex Johnson, Bill and Michael Ward, Murray Herd, Julie Ray Gregg, Bryan Lawrence and Margaret Holmes.

A special thank you to Hugh, Hilary and Julius Drake Brockman, their cousin Richard de Robeck and aunt Katherine Proby for permission to reproduce the beautiful and witty sketches and watercolours done by Mary Dobie on the May Queens voyage of 1877.

There is no doubt that the pictures are a lovely finishing touch but the heart of the book is in the words and ideas and this is where I have received the greatest assistance and guidance, notably from Caroline Daley and Malcolm Campbell of the University of Auckland.

Together they supervised the original thesis and later Caroline encouraged its development into the present work. Her advice and ideas for further reading sent me down tracks I would never have discovered on my own.

The book was greatly improved by the suggestions made by Jock Phillips who read the penultimate version of the manuscript and by Anna Rogers who edited the final version.

I would also like to thank Elizabeth Caffin and the staff at Auckland University Press Anna Hodge, Katrina Duncan, Christine OBrien and Annie Irving for their great work and enthusiasm in producing the book.

Finally, a big thank you to my wife, Clarissa, who has been steadfastly encouraging throughout even though at times it must have seemed like living with Mr Casaubon.

In June 1870 the young and ambitious New Zealand treasurer, Julius Vogel, outlined to Parliament his plan to revive the colonys flagging economy. Everyone expected him to include some form of government-assisted immigration and public works but they were astonished at the audacity of what they heard. In his three-hour speech Vogel announced a plan to spend 10 million, 6 million of which was to be borrowed, to bring growth and prosperity to the new colony. Roads, railways and land purchases would cost 8.5 million; the rest of the money would finance an immigration scheme to populate the countryside. To many who heard the speech, Vogels ideas, unfettered by maturity and experience, seemed to contain the seeds of economic ruin rather than salvation.

A reporter for the Otago Daily Times wrote that he had never before seen an important ministerial statement so coldly received. There was not a single genuine expression of approval in the House but there were frequent ironic cheers. Some thought the colonial treasurer was enacting a farce. One member declared he had never heard of a scheme so wild, so unpractical. Another thought it the most extravagant scheme ever proposed in New Zealand. But others, more cautious, kept an open mind, presumably to see which way the winds of public opinion might blow.

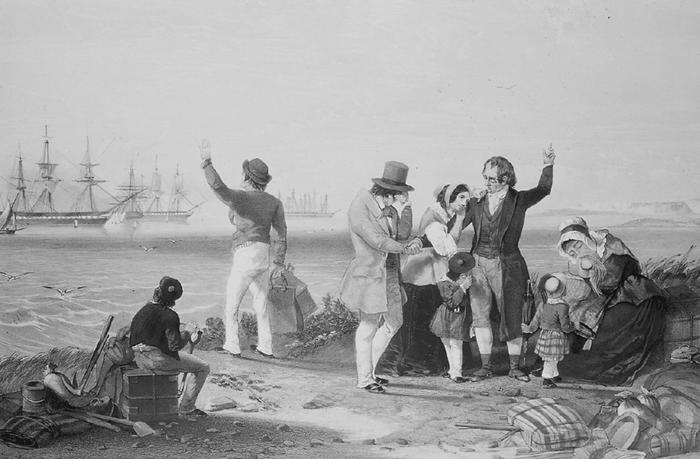

The Lord be with you: James Fagans lithograph of an archetypal scene in the mid-nineteenth century. Sixty million people poured out of Europe between 1840 and the beginning of the Second World War. C-015-001, ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND

The migrants who came as a result of Vogels large measures were part of a great diaspora that saw 60 million people pour out of Europe between 1840 and the beginning of the Second World War. A map in an old history book shows this diaspora as a series of arrows emanating from a Europe located confidently at the centre of the world. The thickness of the arrows indicates population flow. By far the thickest points to the United States of America, next comes Latin America with an arrow about a third as wide, then Asiatic Russia and Canada. The Australian and New Zealand migrant flows are joined together in an arrow that is a mere reed beside the ones aimed at the Americas.

Vogels was not the first migration scheme in New Zealand. There had already been three decades of organised migration by private associations and companies as well as provincial governments by the time Vogel came along. But his scheme was much more significant. It marked a transition in power and influence from the old provincial governments to the central government, a transition that was to be complete in 1876 when the provincial assemblies were abolished. Even more importantly, it was on a much grander scale than any previous scheme. By one estimate, the Vogel period, generally taken to be 187085, accounted for about 30 per cent of the net immigration between 1860 and 1950, making it the most influential factor in determining the ethnic mix of Anglo-Celtic New Zealand.

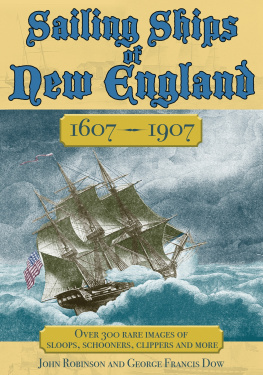

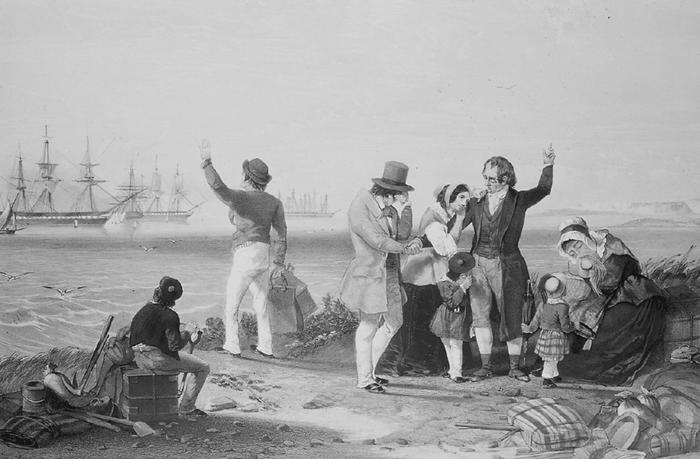

At its peak, in the year to May 1875, the Vogel migration brought 31,785 people to New Zealand on 93 voyages, mostly on sailing ships. the journey during another great transition in history, from one maritime era to another. Just as the age of sail reached its zenith in the form of the clipper ship, it was first challenged and then eclipsed by the age of steam. At first, a full-rigged clipper with a stiff breeze behind it could beat a steamer over a short distance but it was a different matter on the long haul. In the early 1870s the steamer Mongol took just 50 days to reach Port Chalmers. Not even the fastest clipper could match such sustained speed, so it is no wonder that even before the fifteen-year Vogel period was over bigger, noisier, dirtier and faster steamships were taking over the passenger trade and their elegant predecessors were being demoted to assignments carrying filthy cargoes or left to rot.

The zenith of the great age of sail: a clipper in its pomp could beat a steamer over a short distance. But it was a different matter in the long run. 017245, ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND

Early memoirs and histories of the period tell the stories of the great clippers in mythic terms. Basil Lubbock wrote that some of the old ships seem to have the finger of God in their design, the supreme of mans craftsmanship in their building and a touch of genius in their character. These divine ships sailed like witches, survived the severest storms unscathed, summoned fair winds and,

This period also brought about a great transformation in the shipping companies that specialised in the New Zealand trade. It had been a crowded field in the 1850s and 1860s, with at least six companies competing for work, but by the beginning of the 1870s the number had been reduced to two: Shaw, Savill & Co. and Patrick Hendersons Albion Line. They were joined by a third in 1873 when a group of colonists established the New Zealand Shipping Company. Ten years later the number was reduced to two again when Shaw Savill and Albion merged. Not surprisingly, these companies expanded and changed with increasing demand for immigration and the advent of steam. Only seven small ships flew the Shaw Savill flag in the late 1850s but the company bought 31 vessels after 1870, including 4 steamers, and the New Zealand Shipping Company had 23 ships, including 5 steamers, in its first 12 years. Like the histories of the ships and memoirs of the sailors, histories of the shipping companies emphasise their great achievements. A history of Shaw Savill, for instance, cited the companys claim that the steerage quarters of one of its ships were fitted up in a style of the greatest comfort and convenience. It also emphasised the claim that regulations governing the provisions and fittings of all migrant ships were carried out in a spirit of fairness.