Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2013

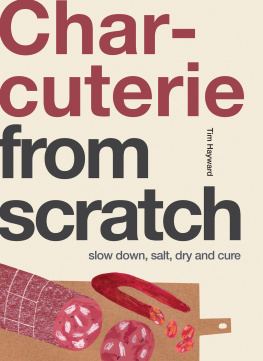

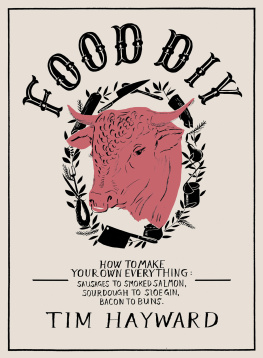

Text copyright Tim Hayward, 2013

Photography copyright Chris Terry, 2013

Illustrations copyright Nicholas John Frith, 2013

Photograph

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-0-241-34157-5

BARON JUSTUS VON LIEBIG

Justus von Liebig was the father of organic chemistry and discovered the importance of nitrogen as a plant fertilizer but thats not the reason hes one of my great culinary heroes. He discovered a way of extracting the nutrients from cheap offcuts to feed those who couldnt afford real meat and started the Liebig Extract of Meat Company later trademarked as OXO. His discovery that yeast could be extracted in the same way means he also gave us Marmite. Were this not enough, his company was the first to develop and ship canned corned beef from its factory in the Uruguayan town of Fray Bentos.

WE SALUTE YOU.

DO-IT-YOURSELF

In the corner of my office is an ugly little bookcase. Its about 60cm long, the sides are not quite at right angles to the bottom and it wobbles. I dont throw it out because I made it. In fact its one of the first things I remember making. Obviously there had been embarrassing hand-coloured Christmas cards for Mum and one of those desk tidies made of toilet rolls for Dad, but the bookcase, made in a school woodwork class, was the first thing I remember planning, cutting, fitting, fettling and finishing, the first thing I took home to my family with a surge of pride.

The bookcase was the beginning of a life of making things. I was an obnoxiously practical little kid, always assembling and disassembling anything from Airfix kits to pet rabbits. In fact, in a childhood that sometimes felt disorientating and scary, I grew to trust a basic mechanical understanding. If you understood how things worked, how they fitted together and why they did what they did, there were fewer unexpected and unpleasant surprises.

I made model planes, fixed bicycles, learned to strip down car engines and outboards. I screwed up plenty of things but I learned a lot more. Later I was lucky enough to go to one of those art colleges where you learned everything from welding to screen printing, from film-making to letterpress. In none of these individual skills did I particularly excel I wasnt destined for a career in stained glass or botanical illustration but I and the people around me set great store in understanding. Each creative action improved our appreciation of our materials, of practical design, of the history of a craft and of art in general and our place in a seemingly endless descendancy of craftsmen. I wasnt a tailor but I knew enough about cutting a suit to talk to one. I wasnt a mechanic but no one was ever going to tell me a gasket was blown when only the timing needed adjusting, and Id always be able to clear a blocked drain.

In spite of my ugly bookcase I didnt go on to be a cabinetmaker, nor a car mechanic, a tailor or a carpenter these days, in fact, I write about food but though I love the flavours, the smells and the sensual pleasures of cooking Im still fascinated by the craft elements. Quite aside from how bloody marvellous it tastes in a sandwich, home-cured bacon is an opportunity to understand more. Butcher the pork and understand the animal better, brine the meat and feel how its texture changes and how its chemical makeup becomes hostile to bacteria. Watch the meat firming up and connect with the generations of smallholders who killed their prized pig and stored its meat through the winter, and, finally, whack off a thick slice and cook it up for the family.

Theres quite marvellous bacon to be had from your local artisan butcher, from the deli or even, at a pinch, from the supermarket, so nobody is suggesting that you cure your own, once a month, for the rest of your life. But just once is enough to make the connection. To understand bacon, its history and its cultural significance in a far deeper way than from the glib rubric on the back of the pack.

Across much of the world, Food DIY is a way of life. Hunting and fishing dont have the same aristocratic connotations as they have in the UK and are enjoyed by all sorts of people. In the US and Europe recreational hunters are used to butchering their kill, smoking, drying or otherwise preserving it, often in a suburban garage with equipment bought from a local hardware store. While in the UK air-drying a ham might be considered either an obscure hobby or something left to specialists, in Italy or Tennessee youre just as likely to find one hanging in the garden shed as a bike or a lawnmower.

Whats most noticeable is that in other food cultures, these exercises in preserving are not seen as the weird pursuits of a food freak but just part of the seasonal duties of the household, like clearing the gutters or burning dry leaves.

In the UK, where food preservation is taking place its seen firmly as a rural pursuit, something that goes with a Barbour and an Aga, but in US cities recently there has been something of a movement towards Urban DIY. Perhaps mirroring an increasing interest in a craft movement, food lovers have begun building smokehouses on balconies, bread ovens on rooftops and hanging salamis out of windows to dry. These new urban DIYers couldnt be further from the image of the Little House on the Prairie homesteader or back-to-the-land hippy, sporting tattoos, piercings and getting very, very serious about meat. Theres even a political edge, a sort of punk/anarchist seizing the means of production that recalls the Diggers, or the allotment movement.

Now, as then, theres something empowering about grasping back food production from industry and middlemen and a dignity in providing for your family feelings a thousand miles from the unhealthy way food has become another branch of consumerism; conspicuous consumption in the most literal sense.