About

the Author

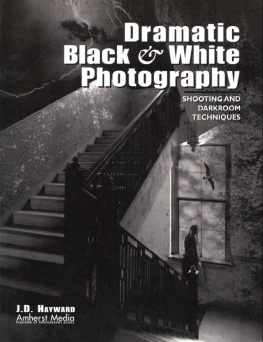

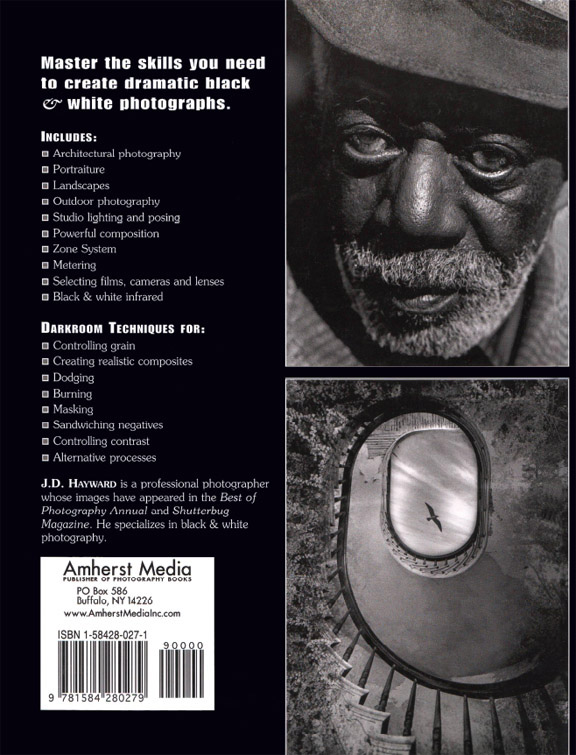

There are many artists and photographers who come strictly from the rigid workshops of the fine arts colleges and workshops; their eye has been fine-tuned and carefully coached by their instructors and mentors. J. D. Hayward did not fit into this mold. At age eighteen, without any formal training in photography, he quickly picked up a camera and created portrait and scenic images that immediately caught the attention of the professional photographers in Northwest Florida. One year later, the Pensacola News-Journal , becoming weary of their journeyman staff, hired Hayward as a freelancer for their new Sunday magazine, Image . For the next two years, Hayward's images were featured weekly on the front cover of the magazine.

Times got even better for Hayward when he opened a commercial studio in the old waterfront area of Pensacola. The contacts and assignments grew rapidly, and his creative talent was well-received. It was a great time to be a young and talented photographer: Vietnam was causing protests, skirts were getting shorter, free sex, drugs and rock and roll were abundant, and photography was being looked at with a new and unjaundiced eye. Through pure happenstance, Hayward was born at the right time, and found his place in the middle of all of thisphotographing the late 1960s.

The early 1970s started to show a political and social change, and this sense of change washed over onto Hayward as well. He decided to make a career change, and began pursuing a degree in the Finance and Accounting Program at the University of West Florida. He completely dropped out of photography and joined the working ranks as a stockbroker with the firm of A. G. Edwards and Sons, where he remained employed for the next five years.

A trip to New Orleans in 1983 renewed and totally recharged Hayward's dormant photography genes. By blind luck, he walked into the photography studio of Johnny Donnell in the Old French Quarter. Hayward was taken with the superb quality of the black and white images of Southern scenes created by Donnell. He was more dumfounded to find that these fine prints had been created with a 35mm camera, and craftily printed on fiberbase paper by Donnell. Hayward's enthusiasm kept him (much to Donnell's dismay) picking the photographer's brain on every question he could think of regarding fine art black and white photography printing. After several hours of answering the unending barrage of questions, Johnny Donnell gave Hayward a box of Ilford black and white paper and suggested that he take a test run in the darkroom. Hayward put the knowledge he had gained to use, and was quite impressed with the results. Upon his return from this New Orleans trip, he built a darkroom far superior to any that he'd had before. By 1986, Hayward had been reborn as a photographer.

The following year, after much trial and error in the darkroom, a friend suggested that Hayward attend a wprkshop in Carmel, California, to fine tune his approach to the Zone System. By coincidence, one of the instructors was the noted photographer Allan Ross, who had been an assistant to and printed for Ansel Adams. Ross, upon reviewing Hayward's portfolio, immediately recognized the potential of the thirty-nine year old photographereven with a ten-year break in his photographic career. Ross decided that, for Hayward's work to be truly recognized, he needed to gain skill in manipulating the tonal scale of the final print. In short, his print quality had to be equal to master black and white printers like Ansel Adams and Brett Weston.

Hayward was in the right place at the right time. Ross quickly corrected Hayward's approach to using a light meter, specifically the Pentax Spotmeter. Sitting on a rock overlookng Point Lobos State Reserve in California, Ross pulled a roll of white tape from his camera bag, numbered the zones from one to ten on it, and stuck it to Hayward's light meter. Ross then explained the Zone System, and how to find the correct exposure for a scene you previsualize based upon correct metering, exposure and development time. Hayward returned to Florida with a renewed sense of enthusiasm for his work and his future negatives. In a short time, the prints he began producing had the look of a master printer and photographer.

Art shows and exhibitions in the Southeast United States kept Hayward busy with his landscape images for the next three years. However, the demand for his portrait and advertising work diminished the time available for him to travel in search of the perfect image. Rene Margruete's surrealistic paintings had intrigued Hayward since high school, so without the time to be on the road in pursuit of new images, he started experimenting with combining several negatives in the darkroom into the same print, to explore the surreal on his own time. His early attempts were somewhat displaced, with no central theme or idea to hold them together. A photography professor from a community college observed Hayward's early attempt at surrealism and remarked to him, "It looks as if you have been influenced by Jerry Uelsmann's work." (Uelsmann has been the Graduate Research Professor of Art at the University of Florida since 1964.) Although he knew of Uelsmann, Hayward had never seen the master's work. Upon being shown original Uelsmann prints by the community college professor, Hayward exclaimed, "They are finer prints in quality (tonal scale) than Adams or Westonand a lot more creative!"

Uelsmann's work made an impression on Hayward's mind more powerful than the professor would ever know. The images that had been on the drawing board in his mind would now be birthed. He was now a confirmed surrealist (which sounds like a religious conversion), and today, much to his esteem, buyers of photography are collecting the haunting works of J. D. Hayward.

The Concepts

The idea of creating photo-montages or printing more than two negatives on the same sheet of paper is almost as old as photography itself. Photographers have used this process since before the turn of the last century. One of the main purposes of this book is to help the student and beginning professional accomplish this with as little complication as possible. Multiple image printing, montages, and overlay prints all have the same thing in common: it's a creative reinvention of the original scene to a new visualization of something that has never existed. Also, I would like to emphasize that this is not a complicated task, but something that should be an enjoyable darkroom experience. For the sake of simplification, I will go through the basics of the techniques here for those who are new to the process.

DODGING THE PRINT

"Dodging" is nothing more than simply withholding light from the photographic paper in your enlarger, thereby printing select portions of your negative lighter than they would otherwise be. To withhold light from exposing designated areas of the print, you can use tools as simple as your hand or a spoon for small areas. Some photographers simply use a stiff wire with cardboard shapes that are cut to their specifications taped to it.

As an example, if you wanted to create a portrait print with "no face," only hair and ears, it would be as simple as making a tight fist with your right hand and holding this hand under the enlarger to block out the eyes, nose and mouth while exposing the portrait negative on the paper. The resulting print would be a wellsculpted face with forehead, hair, chin, ears, etc., but a voided white space where the eyes, nose and mouth were. A section where your wrist was blocking light would also be blank. To avoid this, you could have used the aforementioned wire technique. Cut out a circular piece of cardboard, tape this to a wire, and use the wire to place the circle of cardboard over the area you wish to have missing from the print.