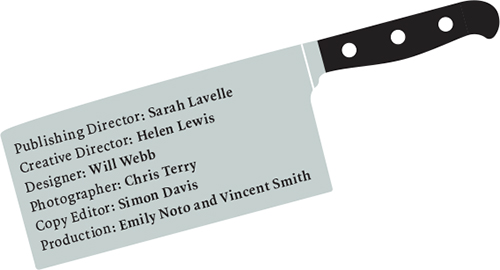

First published in 2016 by

Quadrille Publishing

Pentagon House

5254 Southwark Street

London SE1 1UN

www.quadrille.co.uk

Quadrille is an imprint of Hardie Grant

www.hardiegrant.com.au

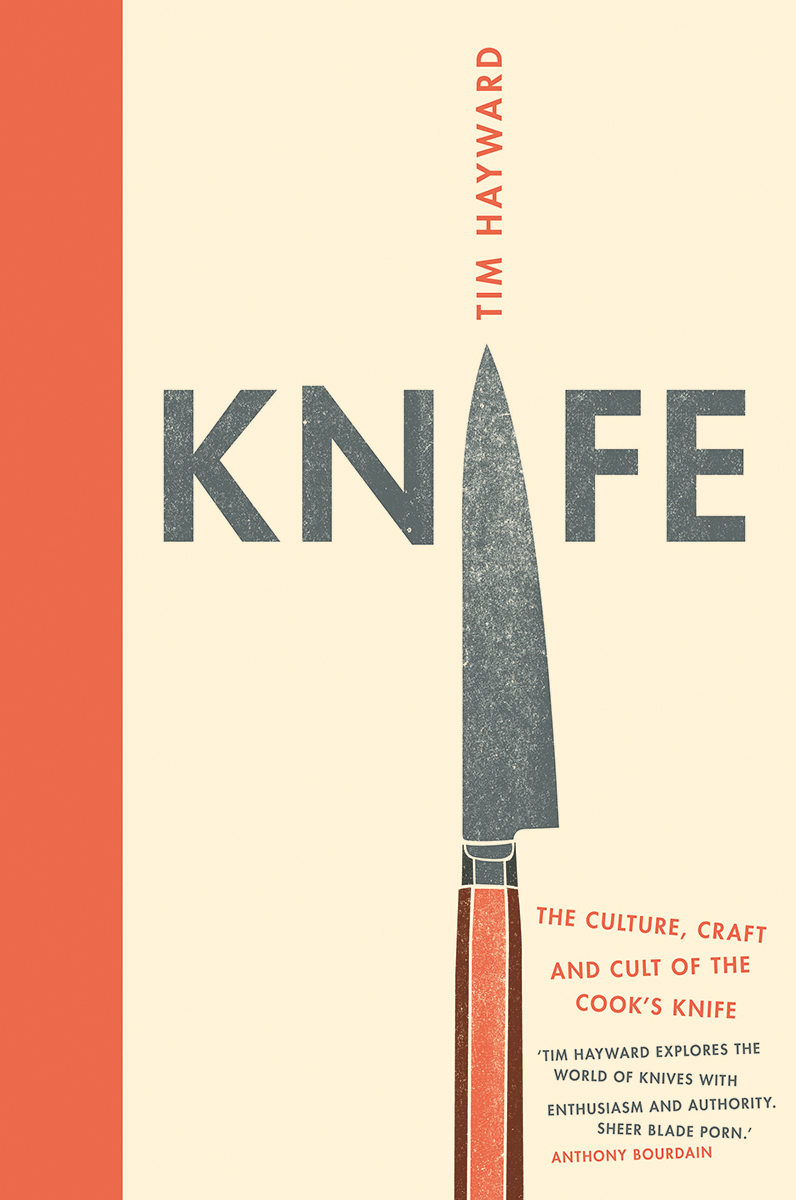

Text Tim Hayward 2016

Photography Chris Terry 2016

Illustrations Chie Kutsuwada 2016

Cover illustration and knife illustrations Will Webb 2016

Design and layout Quadrille Publishing 2016

The rights of the author have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of thisbook shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without writtenpermission from the publisher.

Cataloguing in Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is available fromthe British Library.

eISBN: 978 184949 9361

CONTENTS

THERE IS NO OBJECT YOU OWN that is anything like your kitchen knife.Every day you pick it up and use it to create and transform. This, I suppose, couldbe true of a paintbrush or a keyboard, but the knife is more than a creative or functionaltool. Unless, for example, you are a very particular sort of person, the knife willbe the only item in your possession designed to cut flesh. Think about it eightinches of lethally sharp, weapons-grade metal lying on your kitchen table, possessingthe same potential for mayhem as a loaded handgun and yet it is predominantly usedto express your love for your family by making their tea.

The knife is one of the few objects to which we give house room while simultaneouslyfearing. My Old Nan, bless her, didnt quite trust gas and was genuinely relievedwhen, after the War, she finally got The Electric. I remember my mother quietlydisposing of the pressure cooker and the deep-fat fryer as soon as she could. Weare a risk-averse populace now and have purged our households of dangerous objectsexcept the knife. Nor is the knife an easy option: its the only remaining domestictool that we must discipline ourselves to master rather than taking it out of abox, switching it on and expecting it to serve us. Most of us learn from a parenthow to use and respect a knife. We commit time and effort to our knives, caring forthem, sharpening them, washing them carefully, reverently putting them away in ablock, on a rack, in a box. Should we be surprised when what begins as a simple relationshipbetween human and tool so easily elides into a kind of cultist fetishising? Whatis it about knives that makes us feel this way?

Like most things that we use every day, including our own bodies, a knife will changeits shape and functionality over the course of its life. I once sat in a tapas barin Barcelona and spotted the chef using a knife Id never seen before. It had a handlelike a standard 3-rivet Sabatier but the blade was a wickedly sharp little talon,about an inch long. My Spanish is appalling but I managed to get the owner to explainit. Once, he said, demonstrating with his nicked and burned hands, it had been asix-inch blade, but over 14 years hed sharpened it down to this and every workingday he used it just to slit the skins from chorizo. There isnt, as far as Im aware,a chorizo peeling knife in any kitchen supply shop, but theres certainly one behindthe bar at Cal Pep. Its knackered, worn, beautiful and its the child of its owner,its working life and its environment. His knife is a perfect example of wabi-sabi,a Japanese word that conveys the aesthetic appeal of something worn and shaped byage and use, the very embodiment of evanescence and acquired character.

The knife is the day-to-day working tool of different craftspeople working with food.Chef s knives are similar to those we keep at home, while the knives of people whocut meat or fish all day are different. Like any craftsmans tools, they are evolvedto the work they do and imbued with the spirit of those who work with them. The delicatetourn knife in the hands of a commis chef carving fruit is a million miles fromthe lethally curved gutting knife in the hands of a trawlerman at sea and yet bothhave developed, through generations of skilled and specialised use, to share a beautifulsimplicity of function.

Because knives are also weapons of war and tools of slaughter they are attended inmany cultures by conventions that go so far beyond mere rules that they become taboo.In the West we are used to having knives by our plates but many cultures forbid thepresence of something so dangerous at the communal table. Its logical that, in aplace where food is shared and hospitality is expressed, there should be no placefor a weapon. These conventions go so far back in many cultures that they have affectedthe entire cuisine.

Our national knife styles can be as unique and individual as national dress or evenlanguage. As knives are primarily used in the preparation of food they are as variedas our cuisines and as affected by local ingredients, economies, beliefs and taboos.There is something wonderful in the idea of the knife as a symbol of massive humandiversity and, somewhere, I hope that book is being written.

Far more exciting to me than the infinite subtle differences, are the similarities.This book doesnt attempt to be comprehensive. Instead its a very personal selectionof knives from around the world, chosen for the way they represent different physicalqualities and how these resonate through the knives of different cultures and cuisines.With so much variety in knives globally it is genuinely a revelation to realise thatthe human grip is universal, that the ways we have grown to feel we can control thedanger of blades transcend nation and culture. Most exciting is how the design responsesof craftsmen throughout history, of every level of skill and artistry, from the shokuninof Japan to a woman making work knives from scrap metal in a market in India, endup so aligned. There must always be a heavy knife; its throat must be deep enoughto protect the knuckles in a hammer grip. It takes advantage of weight, whetherits cutting meat in a carnivorous culture or tough vegetables in a vegetarian cuisine.There must always be a knife for cutting towards the thumb; its blade must be narrow,it has no need of a point and the handle must allow the knife to roll. It doesntmatter whether its made of German tool steel or from a hacksaw blade and recycledpallet wood.

It is intriguing how many cultures have taken a single master knife and developedit to serve many purposes the chef s knife and the cai dao spring first to mind yet also how another tradition, like the Japanese, has seen such value in the ideathat theyve absorbed it into their own knifemaking with developments like the