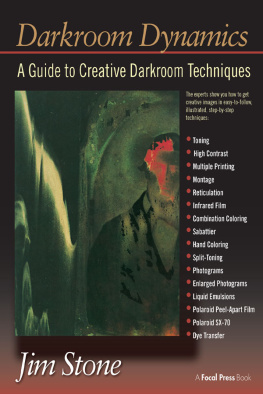

This book is an encouragement to leave the photographic tradition of representation, and to enter a broader area of creative control. The processes presented are not new, but the work reproduced here is fresh and unique. Each chapter, along with its accompanying reproductions , is the work of a practicing artist. These artist/authors have been selected for several reasons. First, each embodies a commitment to, and an understanding of, a specific way of working with photographic materials. Second, each artist has devoted sufficient effort to a way of working that it has merged with that artists vision. Thus the imagery transcends the novelty of the process. Third, the editor and the majority of the artists represented here are professional educators as well, teaching in university art departments across the country. From that wealth of experience come lucid and thorough explanations.

The processes are also carefully selected. None demands more experience with photography than that of processing and printing black-and-white film. All utilize readily available materials, and require little equipment beyond a basic black-and-white darkroom. Each chapter has been crafted to present a procedure in as pure a form as possible. Many processes, however, overlap others, and virtually all can be combined. Toning and hand coloring, for example, can be applied to prints made by Sabattier, reticulation, or photomontage. Although intentionally excluded, conventional color photographic materials can be substituted for black-and-white in almost every circumstance.

It would be no challenge, following the procedures outlined in this book, for you to produce images which seem novel and innovative. The difficulty, and the real creativity, will come with your attempt to sustain that feeling of accomplishment. By the very nature of the included material, the possibilities are endless. Consider the suggestions in this book as merely starting points. There are no rules, and as Harry Callahan once said, thats what makes art better than baseball.

Acknowledgments

The production of this book has been a cooperative project of the highest order. I would like to thank each chapter author for an exemplary job and for tireless cooperation. For production assistance, thank you to Karen Campbell, William E. Crawford, Carlota Duarte, Martha Jenks, Jon Holmes, Arno Minkkinen, Ann Parson, Davis Pratt, Belinda Rathbone, Leslie Simitch, and Kris Suderman. For technical assistance, Dennis Purcell for the Polaroid Peel-Apart chapter, and Frank N. McLaughlin of Eastman Kodak and Larry McPherson for the Dye Transfer chapter. The illustration photographs for the Dye Transfer chapter were made by Alden Spilman. The photograph on p. 5 is courtesy of the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Purchase: Robert M. Sedgwick II fund. The reproductions on pp. 41, 67, and 175 are courtesy of the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House.

Special thanks go to David Herwaldt for editorial assistance, Katy Homans for a beautiful book design, and to both for moral support. Extra special thanks go to my parents, Charles and Sylvia Stone, for everything.

All set-up illustrations were reproduced directly from Polaroid Land Type 52 black-and-white prints made, unless otherwise noted, by the editor or chapter author.

THE SABATTIER EFFECT

John Craig

The French photographer Armand Sabattier discovered in 1862 that unique positive/negative effects could be obtained by reexposing to light and redeveloping an exposed and partially developed negative or print. Ever since then, photographic artists have been intrigued by this phenomenon, commonly though inaccurately called solarization. Many have utilized this effect very successfully in their personal modes of creative photographic expression. An early example is the photographs made from solarized negatives that Man Ray produced in the late 1920s and early 1930s. More recently, such photographic artists as Robert Fichter, Edmund Teske, Jerry Uelsmann, and Todd Walker have creatively used the Sabattier effect in their imagery. Each has dealt with the process in a unique and expressive way that has contributed to the success of his photographic work. I have been fortunate to have come in contact with the work of these artists, and my own imagery has been influenced accordingly.

The Sabattier effect has become a method by which photographers can introduce some painterly graphic elements into photographic image making. Unique and fascinating spatial juxtapositions are created by the combination of positive and negative tonal information in a single print. Photographically real forms become distorted and abstracted.

One of the more interesting results of the Sabattier effect is the creation of Mackie lines, thin white lines on the print formed between adjacent dark and light tonal areas. They serve to separate these areas and accent the positive/negative qualities of the image. These Mackie lines are similar to expressive hand-drawn lines, though they are drawn with light. When working with the Sabattier effect, I feel more like an alchemist or magician than a technician. Subtle as well as dramatic alterations take place on the surface of the print and contribute to a sense of surrealism and the revelation of a separate reality.