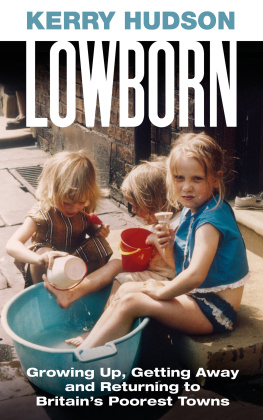

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Tony Hogan Bought Me an Ice-cream

Float Before He Stole My Ma

Thirst

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

VINTAGE

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Copyright Kerry Hudson 2019

Jacket photograph Shirley Baker/Mary Evans Picture Library

Jacket design by Stephen Parker

Author photograph Mark Vessey

Kerry Hudson has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published in the United Kingdom by Chatto & Windus in 2019

penguin.co.uk/vintage

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781473556423

For all of you who have lived this story too.

Introduction

Shall we start with a happy ending? I made it. I rose. I escaped poverty. I escaped bad food because thats all you can afford. I escaped threadbare clothes and too-tight shoes. I escaped drinking or drugging myself into oblivion because because. I probably escaped the early mortality rates and preventable diseases well see. I escaped obesity. I escaped the higher rate of domestic abuse. I escaped sink estates, burnt-out houses and ice-cream vans selling drugs at the school gates. I escaped Jeremy Kyle in a shiny suit telling me my sort was scum. I escaped casual, grim violence fuelled by frustration and Special Brew. I escaped benefits queues and means assessments and shitty zero-hour contracts. I escaped hopelessness.

I lived more of that life, my first twenty years, than Ive lived of this infinitely cushier one since. And the names still ring in my head every day: chav, scav, lowlife, NED, underclass, lowborn.

Yes, I might have been lowborn but, somehow, I ascended. I reached up high enough to write these words and believe someone might read them. Now I eat well and always have somewhere decent to stay. My clothes are cheap, but I can afford to replace them. I enjoy the luxury of exercise. I heat my flat in the winter. I have access to art, music, film, books and they dont feel like a foolishness. When Ive been unwell, in mind or body, Ive sought help, its been given, and Ive got better. Ive travelled the world several times over and made a living doing what I love which also happens to be the preserve of People Not Like Me.

But now lets go back to the beginning:

- 1 single mother

- 2 stays in foster care

- 9 primary schools

- 1 sexual abuse child protection inquiry

- 5 high schools

- 2 sexual assaults

- 1 rape

- 2 abortions

- My 18th birthday

The Adverse Childhood Experiences questionnaire asks ten questions to measure childhood trauma and each affirmative answer gives you a point. Research has shown that an individual with an ACE score of 4 or higher is 260% more likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease than someone with a score of 0, 240% more likely to contract hepatitis, 460% more likely to experience depression, and 1,220% more likely to attempt suicide. I scored 8.

It might be easier to believe that I was somehow unlucky. That I was a terrible exception. But the truth is the people I grew up with experienced much the same. A little less sometimes. Often a lot more. The difference for me? I saw something on the horizon and I ran. I ran, and I never looked over my shoulder.

I am proudly working class and, in this socially mobile hinterland I currently occupy, I miss the sense of community and belonging which that tribe might provide me.

But I was never proudly poor. True poverty is all-encompassing, grinding, brutal and often dehumanising. I think it goes without saying that the gnawing shame and fear of poverty is not something I have ever missed, particularly since I frequently still experience its aftershocks.

While my life is unrecognisable today, I find myself unable to reconcile my now with my past. I can best describe this vertiginous feeling as belonging nowhere and to no one, neither back there nor truly here. I have come to believe that being born poor is not simply a matter of economics or situation, it is a psychology and identity all its own that, in me, has endured well beyond my escape.

This book is the outcome of the questions that still disturb my peace. What happened to those towns I lived in? Surely things got better? There are other questions too, less easy to confront out loud, except perhaps when I wake up at night screaming obscenities at phantom shapes, inky terror running through me. What happened to me during those years? Have I really escaped? Has my fragmented memory been protecting me all these years or has it inflated, year by year, this terror? How much of my past is still part of who I am today?

A year ago, I realised I could only really answer these questions if I went back. If I looked my monster in the face in the hope it would only be a shadow, after all.

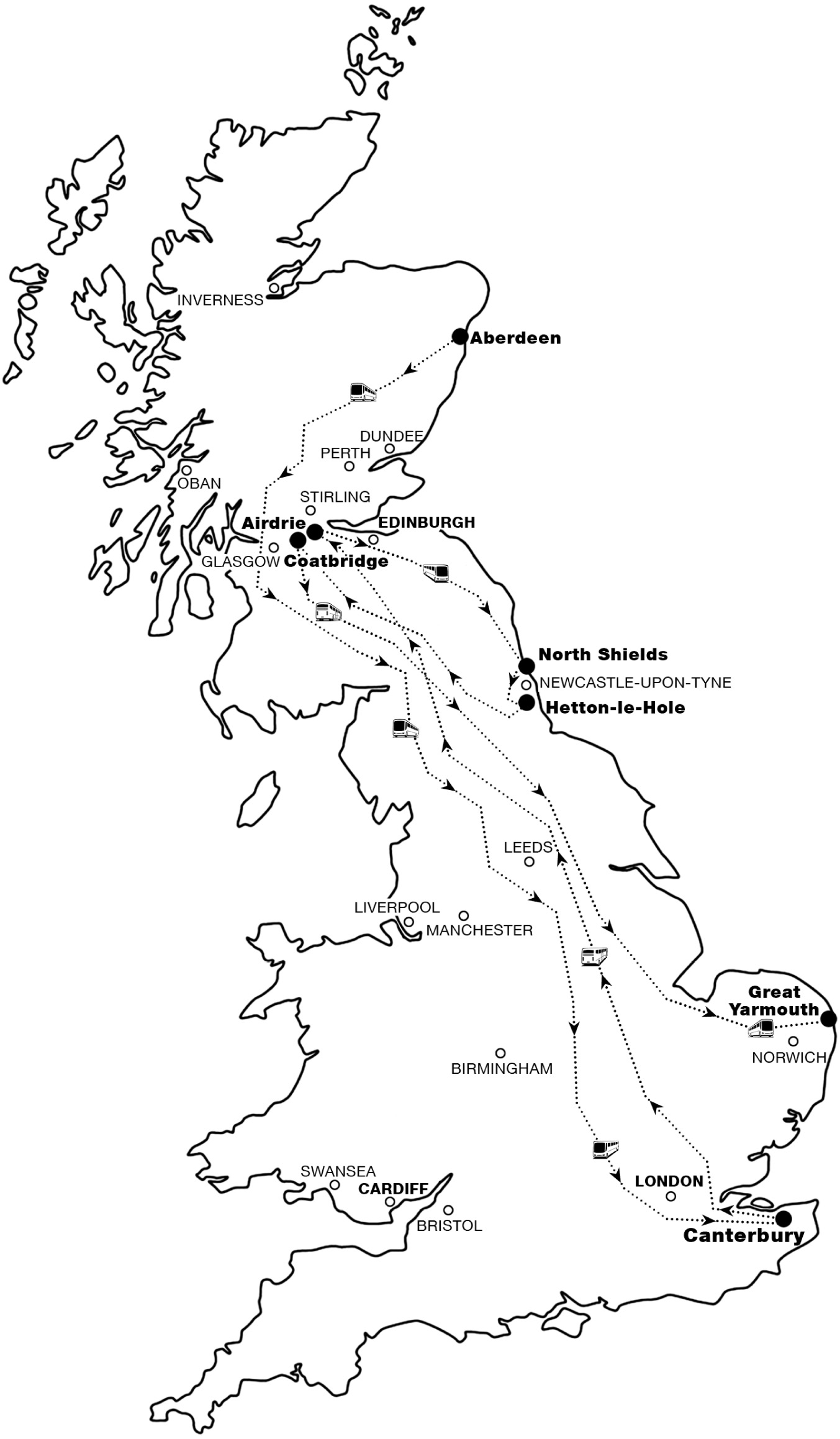

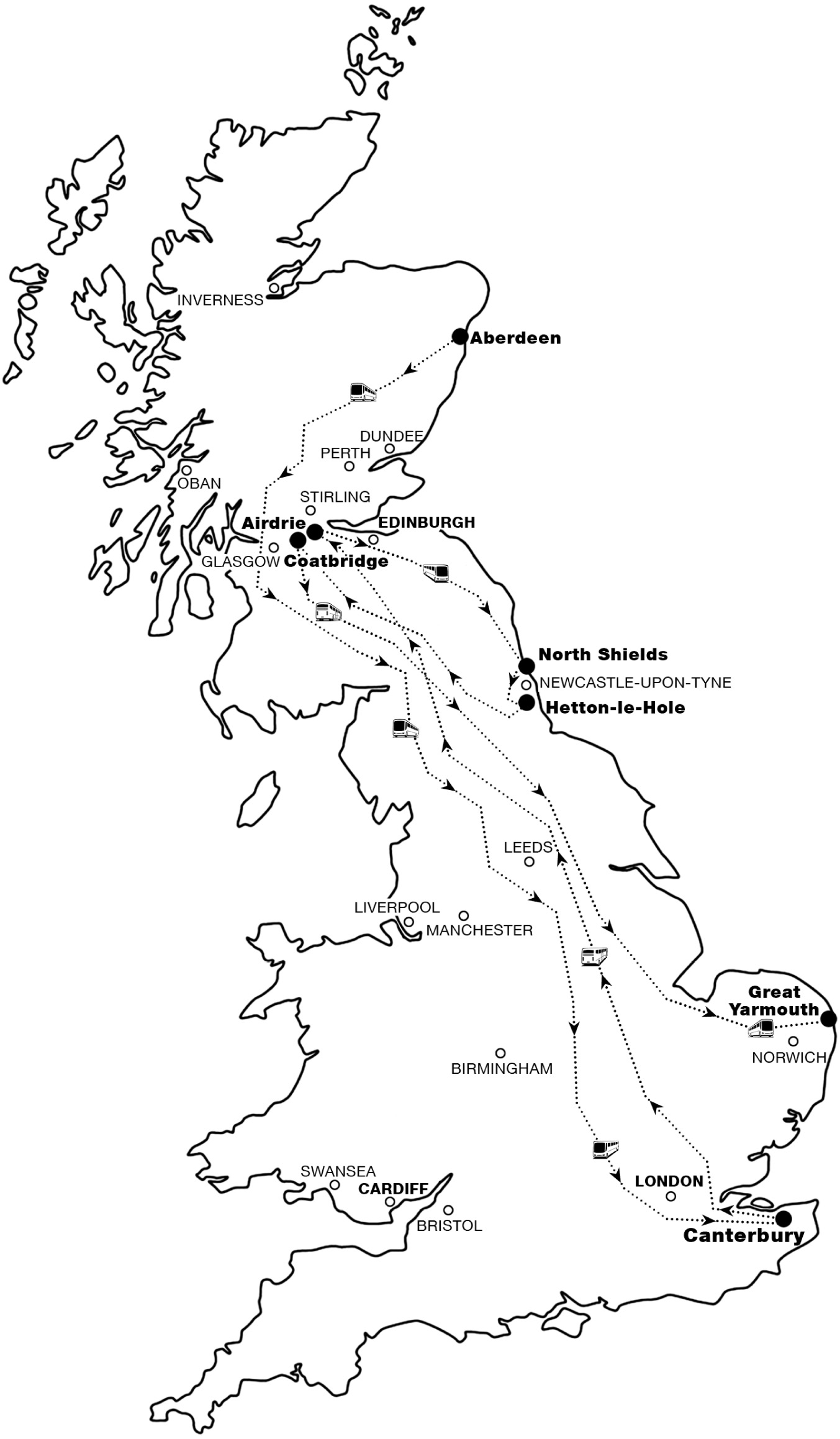

I decided to go back to Aberdeen where I was born into a clan of matriarchal fishwives and follow the staggering, itinerant route of my childhood down the country: Aberdeen, Canterbury, North Lanarkshire, Sunderland, Great Yarmouth. Not so different from my ancestors chasing herring, silver darlings, down the line of the coast, but I would be casting my net for stories and facts, then Id cut them open and see what the guts told me.

Did those towns die with the decline of their traditional industries? What was it like to be poor or working class and living there now? What did working class even mean any more? If I was a child or a teen growing up there today would there be hope? Who lives where I used to? What about the kids on the streets? I planned to simply ask those questions to people going about their daily business, and to those working on the front line of austerity and at grass-roots level, people new to those towns and people whod lived there for decades, to see how these communities were living and surviving or not.

As I went up and down the country Id retrace my own childhood and try to fill the gaping holes in my memory by requesting my child protection documents, medical and school records, by hunting down anyone who might remember who I was. Anyone who could maybe remind me, too.

I decided to seek answers to my questions because, now, I believed I could open my mouth to ask and not be punched or punished or ridiculed. Because my happy ending needed to be tested so I could sleep through the night. Because, if it was a happy ending, I should care about what I left behind. I should stop, look over my shoulder and understand what I came from.

When every day of your life you have been told you have nothing of value to offer, that you are worth nothing to society, can you ever escape that sense of being lowborn no matter how far youve come?