Mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities in this book does not imply endorsement by the author or publisher, nor does mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities imply that they endorse this book, its author, or the publisher.

Internet addresses and telephone numbers given in this book were accurate at the time it went to press.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher.

ISBN 9781623362959

eISBN 978-1-62336-296-6

We inspire and enable people to improve their lives and the world around them.

rodalebooks.com

INTRODUCTION

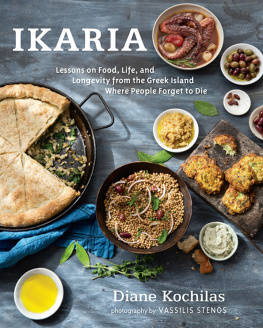

Ikaria feeds the soul.

I first touched foot on the island in 1972 as a 12-year-old New York City kid inured to sticky urban summers, insipid American food, and strict curfews. My Greek was nonexistent, but somehow it didnt matter. I felt at home, as though Ikaria was in my bones. It was, I guess. I grew up with it all around, the child of Ikarian immigrants. My father left his village, Raches, in 1937 and never was able to make it back, settling instead, right after the war, in New York City. Despite our physical distance from it, Ikaria was woven into the texture of our lives. We lived in an Ikarian enclave in Jackson Heights, Queens, and all my parents friends were from the island; by default and design, we kids were also friends. Now, so are our own children. Bonds among islanders from Ikaria cross oceans and generations. We never thought these ties and our roots to the island to be anything but the norm, even in a society as mobile as America.

Historically, Ikaria has always been isolated and poor, a speck of rock 99 miles long in the middle and roughest part of the Aegean, where political undesirables were exiled from the Byzantine era to the 1960s. But in remoteness and want, islanders learned to be self-reliant, independent of thought, and close-knit, to disdain the pursuit of material acquisition and live simply and essentially, to pay little heed to the zeitgeist of the times, indeed, to pay no heed to time at all. Ikaria is known as the island where people do not live by the clock, where punctuality is not necessarily a virtue, where the time of day is always late thirty, a kind of running joke. Yet, they outlive most clocks, for the island is home to some of the longest-living people on earth, a demographic and statistical anomaly that has catapulted Ikaria and its people to unexpected fame in the last few years.

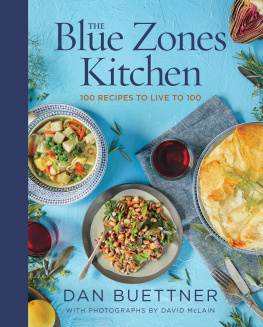

Ikaria is one of the Blue Zones, a term coined by the Belgian demographer Dr. Michel Poulain, who together with Dr. Gianni Pes of the University of Sassari in Italy and Dan Buettner, author of the book The Blue Zones, have been studying the planets pockets of longevity since 2003, under the aegis of the National Geographic Foundation and, in the case of Ikaria, the AARP as well as a series of other corporate funders. Poulain, blue pen in hand, literally drew circles (in blue) on the map one day around places such as Ikaria, Okinawa, Sardinia, Costa Rica, and a community of Seventh Day Adventists in Loma Linda, California, where people seem to live an inordinately long time. His blue-circled zones gave birth to the term that has become synonymous with longevity, but the trademark is owned by Buettner.

What sets Ikarians apart, even from other nonagenarians around the world, is that they live wellwith little cancer, cardiovascular disease, dementia, or other age-related ailmentsdrinking wine, enjoying sex, walking, gardening, and socializing, in other words, being very much alive, in their veritable, modern-day Shangri-La. Since 2008, a battery of scientists, journalists, demographers, and others has been trying to figure out the secrets to this seeming paradise. Food, lifestyle, and such a deep-rooted disregard for living by the clock that there is really no stress have all, somehow, played a role in giving Ikarians good, long lives.

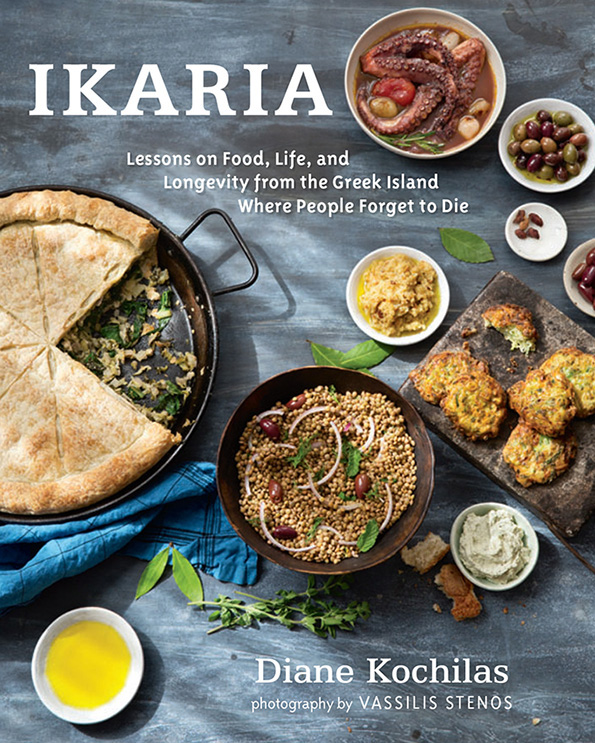

In this book, a tribute to the place and to our countless friends there, both of which have given me and my family more than words can ever express, I set out not to codify Ikarias diet or lifeways in hopes of uncovering some key, but, rather, to honor them and shine a loving, and, I hope, knowing, light on this once-forgotten piece of rock, that looks like a wing and is named for the Icarus of Greek myth. I hope that anyone who picks up this book might glean a few lessons for how to live more essentially and less anxiously, by cooking and eating simple, real food that is largely plant-based, by ignoring the clocks reign, if even for a bit, and by forging relationships that defy generations and are both meaningful and long-lasting. Those are the things Ikaria has given me and that I hope to share with others.

IKARIAS LONGEVITY DIET

In researching the diet and foods that people who are now well into old age ate while growing up, I consulted Dan Buettners book (The Blue Zones), read through the Ikaria study (which was compiled by a group of international scientists), and asked a lot of my own questions of the 80-plus set on the island. What I discovered was that it wasnt so much what people ate a generation or two ago on Ikaria, but it was more the fact that they simply did not eat very much at all. Food was not nearly as plentiful then as it is today, so if anything, the dearth, rather than the type, of food defined their diet.

Equally important, of course, was and still is the quality of food. On Ikaria, to this day, people eat very little processed food. Sure, fast food has made some inroads, mainly in the form of souvlaki joints, pizzerias, and a few places selling handheld phyllo pies, most of which are slathered with hydrogenated oils. Chips, candy, and the kind of ice cream so filled with stabilizers that it doesnt melt even under an August sun (an experience I had with my own daughter a few years ago on the island) are all now, unfortunately, part of the dietary vernacular. But so are the wild greens and tomatoes and fruits picked in season, fish just minutes out of the sea, the pigs raised in the family barn and fed leftovers from the table and acorns from the forest, the goats that are grazed or fed on clover and bramble, and the chickens that also eat scraps left over from dinner.

, recycled paper

, recycled paper  .

.