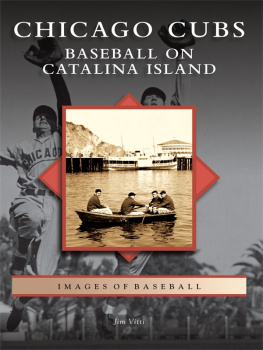

Island Notes

Finding my place on

Aotea Great Barrier Island

Tim Higham

Illustrated by Harry Higham

Text Tim Higham 2021

Illustrations Harry Higham 2021

Tim Higham asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this book.

This book is copyright apart from any fair dealing as permitted under the Copyright Act, and no part may be reproduced without permission from the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Edited by Mary McCallum.

Cover design by Paul Stewart. Cover photo by Jonny Goosman.

Print typesetting, book design and ebook conversion by Sarah Bolland.

Set in Adobe Caslon Pro at 11.5/15

Author photo by Saskia Koerner.

Visiting Mr Shackleton by Bill Manhire and epigraph by Jeanette Aplin used with permission of the authors.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand. Kei te ptengi raraunga o Te Puna Mtauranga o Aotearoa te whakarrangi o tnei pukapuka.

ISBN: 978-1-98-859540-5 (paperback); 978-1-98-859554-2 (epub)

Published with the assistance of Creative New Zealand.

The Cuba Press

Box 9321 Wellington 6141, Aotearoa New Zealand

to Julie Anne

If you really want to rediscover wonder, you need to step outside of that tiny, terrified space of rightness and look around at each other and look out at the vastness and complexity and mystery of the universe and be able to say, Wow, I dont know. Maybe Im wrong.

Kathryn Schulz

And, because you love me, you will come to me again and again and forgo a thousand opportunities to live out other dreams and go to other places.

Jeanette Aplin

HOME

It is mid-winter on Aotea Great Barrier Island.

Julie Anne and I are following a grassy track through swamp country.

Beside us is a drain, overhead knuka.

A pwakawaka flits among its branches.

Dew burns off the rank grass and bracken around us.

Mist hangs in the valley.

A flock of kk tear the silence.

Two-year-old Georgie runs ahead to hutches, where chickens are clucking expectantly.

Julie Anne gathers her up, forehead to forehead, a whirl of gumboots, passed-down jersey and corduroy.

Smiles back at me, a conspiratorial smile that says this could only be an adventure of your making.

Where the track steepens, we become a threesome Georgie swinging between us through eucalypts, a zig zag, to an outlook over crowns of kahikatea emerging from a creek below.

I hoist Georgie onto my shoulders, take Julie Annes hand, along the shaded track toward a clearing.

Our mission is to check out an intriguing property that has revealed itself via 56K dial-up modem from Bangkok.

It appears to be generous farmhouse among stately trees, at a price that might just be within reach. So, weve left the rest of the family teenager Jo, seven-year-old Ella and pre-schooler Harry with their grandparents in Auckland.

The clay track gives way to lawn, a curving line of leafless oaks, a couple of small sheds, a twisted flame tree with a rope swing hanging from a bough.

There are boxed vegetable gardens, a stone wall, a gap in a hedgerow

a door in the middle, a window either side, chimney at one end, almost like a childs drawing. The house is more modest than it appeared in the listing.

We sit at a wooden picnic table on the lawn.

Theres a dormer roof and attic windows. Everything is in proportion to the forest clearing.

We imagine our lives within it.

* * *

We were still in our thirties when Julie Anne, Georgie and I walked up the valley that first time.

Purchase negotiations for the thirty hectares took a few weeks. More important than price, the owners wanted reassurance that we would take proper care of two horses that lived on its swampy paddocks.

We were not buying the property, they were selling it to us. We had to be fit for the job.

When the sale agreement was complete, we shared the news with friends passing through Bangkok our home at the time and they jumped at the chance to look after it for a year or two.

It was four years before we returned to New Zealand to move in.

By then, despite the reasonable efforts of the caretaker couple, the house and its gardens had lost their shine.

The front door opened onto a musty, pent-up air. Rat droppings sprinkled stairs and bench tops, fly carcasses were heaped on the windowsills.

A pink stain covered parts of the lower walls, and whitewash crumbled into piles on a threadbare blue carpet.

Julie Anne and I avoided eye contact, suppressing a dread we didnt want the children to detect.

Even now it takes several days to meet the house on its terms; to accept that, despite best efforts and available energy, its drift is towards chaos.

* * *

The house looks like one in the photographs in the centre pages of Ring of Bright Water, where Gavin Maxwell wrote about his life with otters and other animals in the 1950s. Maxwells Camusferna on the Scottish coast had three roof dormers with single windows. Ours has one, with two eight-pane frames set inside it.

When I painted the roof, I changed the colour from forest green to ocean blue. The window frames and porch roof I turned to grey.

I felt initially the house had become too austere, its glacial hues more suited to Maxwells shores or a lighthouse keepers cottage than a bush clearing.

The houses architectural whakapapa is hard to pick. Provenal? We advertised it as such when we wavered, briefly, in our custodial care. It has South African farmhouse roots, Cape Dutch without the round gables.

The houses original faade was whitewash inside and out and the roof was thatched with rush from nearby swamps.

The builders convinced the council that native rush growing on the swampy paddocks had the same properties as Norfolk reed. A seasons scything, drying, bundling and thatching worked for the first ten years of the life of the house. A patch in the southeast corner became its undoing, prompting replacement with Colorsteel and a legacy of spongy upstairs flooring.

The couple we bought the house from left a school exercise book with instructions. How to keep chickens. A no-knead recipe for bread. How to sweep the chimney and how often.

Its dog-eared pages also contained a recipe for making whitewash: 5kg hydrated lime and 1kg of salt in 12 litres of water left overnight and stirred to a creamy consistency, to be applied every two years.

I felt I didnt have the time to paint the house top to bottom that often. With the old whitewash turning green, I coated the house instead with a weather-proof acrylic. I was torn. I wanted to do everything by the book. I wanted to prove I was up to the job.

Julie Anne describes the house as a leaky building.

In a recent northerly storm, the rain pressed in around the eaves and window frames, running inside the blocks and dripping from the top of the downstairs lounge window to pool under the carpet.

Above the gas fridge, on the wall of the kitchen, the paint blisters and crumbles like continents in drift.

Owning the property has been a drawn-out lesson in entropy and a testing of the bounds of marriage.