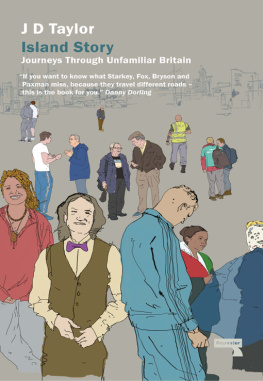

ISLAND STORY

ISLAND STORY

Journeying Through

Unfamiliar Britain

BY J.D. TAYLOR

To my old man

Introduction

Picture the mind as a terrain. Highways, byways, laybys and traps, laid over an expanse as vast as the sun and as predictable as laughter. These roads of the mind ebb and flow like electric charge. Nothing is still, though tranquillity remains a prevailing illusion. Each route is circular, beginning and ending with where you are now.

I have pottered down such paths, searching for some elusive satisfaction that the sages call peace. Others stalk the same terrain with alacrity and obsession, letting grey streets or green horizons imprint themselves with genetic certainty. They commend the well-trodden path, less likely to lose ones footing or track. Habits groove into stubborn repetition: keep off the grass. Others take shortcuts, desirepaths, where grass is gored by impatient feet, the soil bald and smooth, leaving behind a perpendicular line from A to C without the romance of B.

Each mind contains its entire universe, for each senses everything it can know at any given time. And yet if each contains a near-infinite range of imaginary possibility, its remarkable how each senses and acts alike. Neurones and algorithms reinforce similar behaviours for simplicitys sake. Some enjoy telling others to keep off their grass. They talk of territory, not terrain, and navigate by map, not meander. The distinction is significant. For this terrain expands as far as ones ability to sense it, the view from where one stands, sits or crawls.

It may be strange to begin an account of an unlikely cyclo-safari across Britain with a thought experiment. Confusion is at the root of any journey through the unrecognised, assailed by fears of becoming lost, the legality of peeing (or sleeping) in bushes, or not returning home on time. Disliking disorientation, one habitually returns to the familiar. But what is down that way?

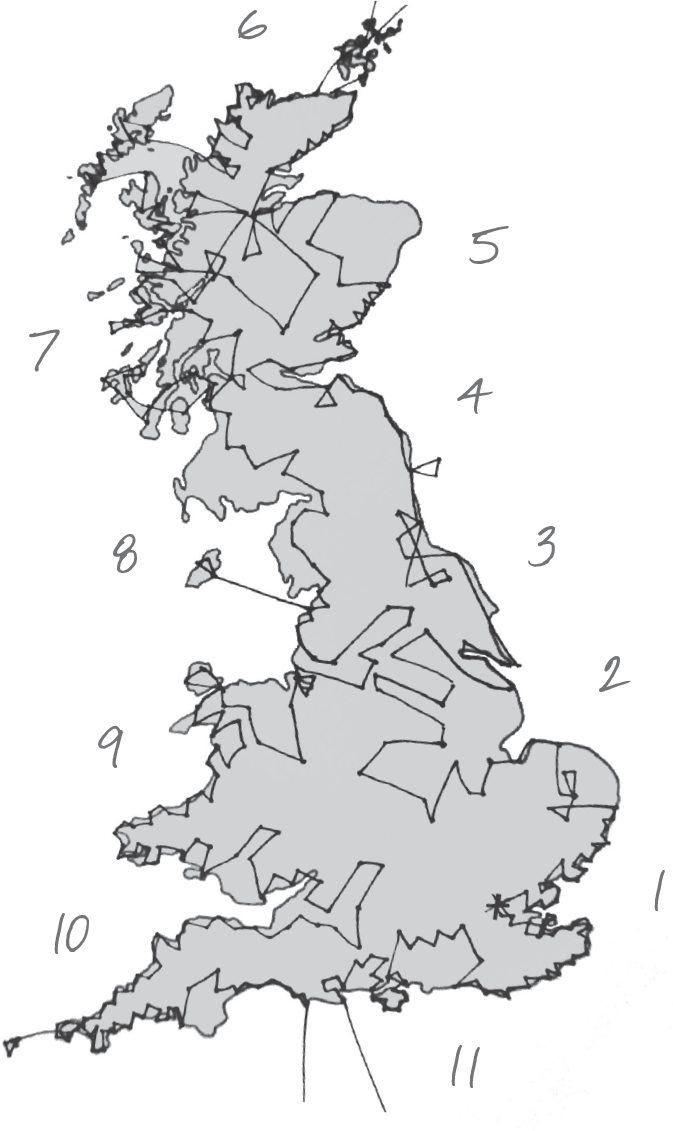

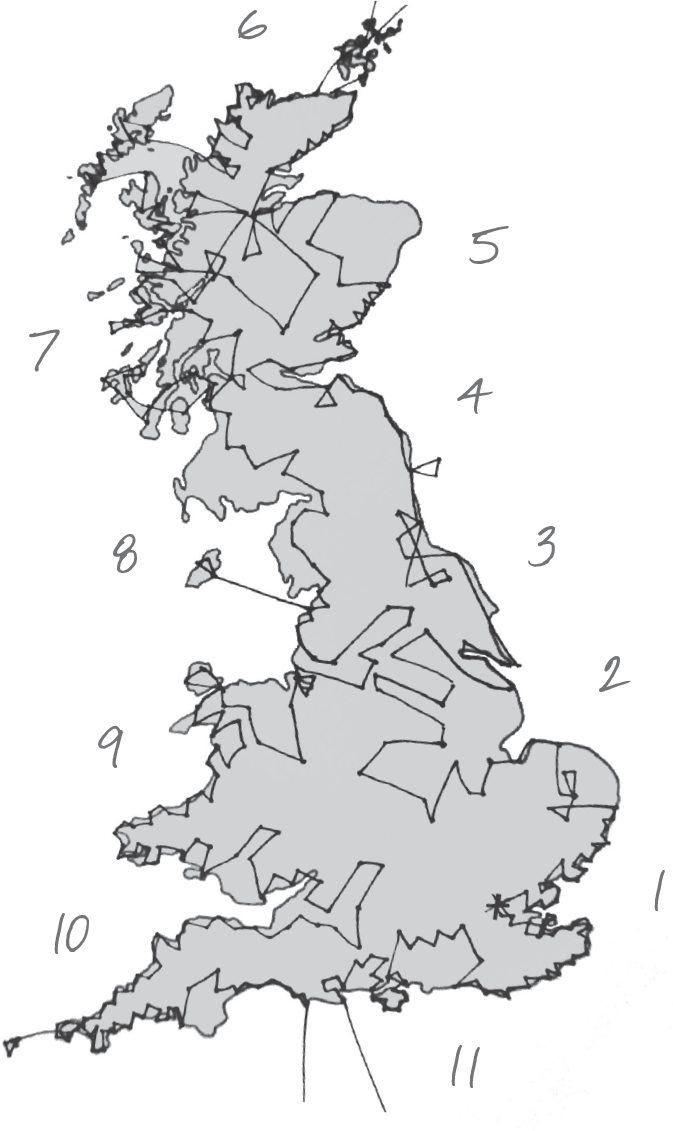

Over four months I went cycling across Britain, gathering stories, seeking out something I couldnt yet name. Serendipity and a smartphone chartered my course, and a compass when either failed. I camped in parks and playing fields, forests and castles, and I slept in the houses of an improbable number of strangers. Some I met in pubs, others had heard word of my journey. Along the way I met farmers and fishermen, miners, nurses and teachers, civil servants and millionaires, professors and probation officers, artists and students, a film actor, homeless people for whom a sleeping bag was no stunt, and many men and women working in the service sector or unemployed, poverty blurring the boundaries. I asked them about their lives. The method was like that of William Cobbett, reasoning with some, laughing with others, and observing all that passes. I transcribed their stories and wrote my impressions, reading widely, pursuing clues, seeking coherency.

The idea to just go out there had embedded itself long ago, resurfacing during emotional dislocation, like stress at work, or an irresolvable falling-out with a close friend. I desired the not-known path, to boot through the brickwork barricading this well-worn way from the splendour of the strange. Serene forest scenes, air zinging with juniper, whatever that smelled like. Intimacy with sun, not screen. But my skint status and a depressed acquiescence tethered me down. I made the common error of confusing disappointment with adulthood. Then something unusual happened.

Good time to rehearse my alibi. For the next many months Id be asked to account for myself. I am twenty-seven years old, a native son of South London. My twenties have disappeared in its bars and its bar work, and working in a brain-injury service and a mens suicide-prevention initiative. Id written benefits applications for carers and then appeals when they were turned down, issued food vouchers and platitudes on how things would improve. Id seen first-hand the cruelty and stupidity of a war against the poor, and a prevailing helplessness that calloused into indifference. I felt unsatisfied by the answers to the left and right of me. In doubting them, I doubted myself too. What did I know? My friends were people like me, Id barely seen much of Britain at all. So I resolved to hear and observe what life was like for others, and from that, make up my own mind.

South Londons lesser state schools strive to blunt the intellectual curiosity of all those who enter them. In my case, they were only partly successful. Ive no Oxbridge credentials or well-connected kin, and live in social housing with my partner. Mines a common story. But hear me speak and I am middle class, unprepossessing, softly spoken. Educations had that impact. Being shy by nature Ive often felt an outsider, blending in with conversational camouflage. My citys a haven for outsiders. Now cranes dominate the horizon, communities being replaced with commercial opportunities, familial homes converted into aspirational housing. Their cause is not endogenous. A paper trail into the tax havens or an anti-capitalist tract could only give half their story. What else could it indicate?

So I sought to make a destination of the horizon, and find out other stories. But the sluggish waters of pubs provide safe harbour for almost every peccadillo. One needs more than discontent and wanderlust. A bung, for instance. Like a PhD scholarship from a small university Id won the year before. Thats the clincher. It gives a modest income to rummage through a dead philosophers treatises on desire. It gives immodest free time.

Id never travelled before, in the gap-year backpacker sense. But I couldnt afford endless train tickets or cosy cottage B&Bs. Means made the method. With no more than a score spent on the tent Id call home, I borrowed or was gifted the rest. And then there was the bike.

Not stolen is it? I asked Bob at his second-hand shop off the Walworth Road. 70 seemed too good, churlish to haggle. Oh no, he chuckled, earnestly. Id learn the truth of this. With ten gears and a rusty chain, the Raleigh Pioneer felt like itd never gone beyond the Elephant & Castle. We had that in common. Its dramatics come later, alongside the eccentrics, sad and hopeful stories, heady encounters, lost histories and bizarre adventures. Between those, the story of an island.

This is no quest to unearth the real Britain or other things of fable. Much of modern national identity is rooted in what people believe about the present and past, rather than whats actually the case. Myths have more operative power. Ossian, Arthur, St George and the Barddas are all fabrications. What will future historians make as their modern counterparts?

In attempting to incorporate many aspects of an island, I cannot satisfy all. The most accurate map has the scale 1:1, like the map of the Empire whose size was that of an Empire depicted by Borges. Such a map serves no one. The last who tried this was John Leland, who fell beside his wits some years into undertaking his Laboriouse Journey and Serche across 16th century Britain, mapping each inch of the island with words. There is no completing any journey; the mind lingeringly retraces its wanderings. This is a work about the pleasure and commitment of journeying. Perspective is one with its location. When ones sense of perspective changes, a new terrain comes into being.

CHAPTER I

Prehistories

You been chucked out or summat mate? Tucker.

Its a fair question. Clearly Id fallen on hard times. Sun long-set, Id re-surfaced on Canvey Island, Essex, from a days forays in blind wilderness. Slimy salty chips from the esplanade, pebbledash squaring off against the cool teal-grey sea. Behind me was Fantasy Island, the sarcastic moniker of a deserted amusement arcade, spangling golds a-glimmer, jingle jungle. The lights of a nearby boozer had compelled me.

Next page