A project like this is only made possible through incurring a string of debts. The editors first of all thank Masako Ikeda of University of Hawaii Press, who provided special fast-track shepherding from beginning to end. Masako recognized the worthiness of this collection, trusted that all the authors would understand the process and deadlines, successfully interfaced with the editorial board of the press, and provided encouragement and guidance throughout. A big mahalo.

The editors are also personally grateful to all the authors involved. This book has had a remarkably quick turnaround from inception to finish, in no small part due to the cooperative hustle of the authors making deadlines and responding to sometimes last-minute requestsin short, helping make this Ric Trimillos project happen. We presented Ric with a book proposal at his seventy-fifth birthday party; the gift of this volume was made possible through the dedication of friends and colleagues contained therein.

Thank you to the University of Hawaii Department of Music for their contribution of a publication subvention to help defray costs. Rics career in that department (as graduate student and professor) and his shaping of the field of ethnomusicology find recognition in this kind of funding. The contribution may not have made this a better book, but it at least will make it a more affordable one. And a special thanks to the editors of Japanese Studies and the Taylor & Francis Group (www.tandfonline.com) for allowing reprint of a modified version of Christine R. Yanos chapter, published in 2015 as Plucking Paradise: Hawaiian Ukulele Performance in Japan, Japanese Studies 35, no. 3: 317330. viii

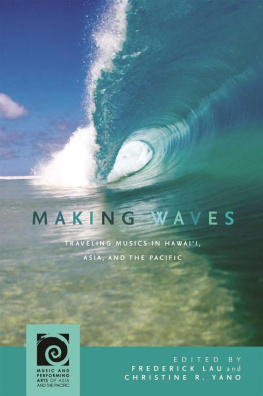

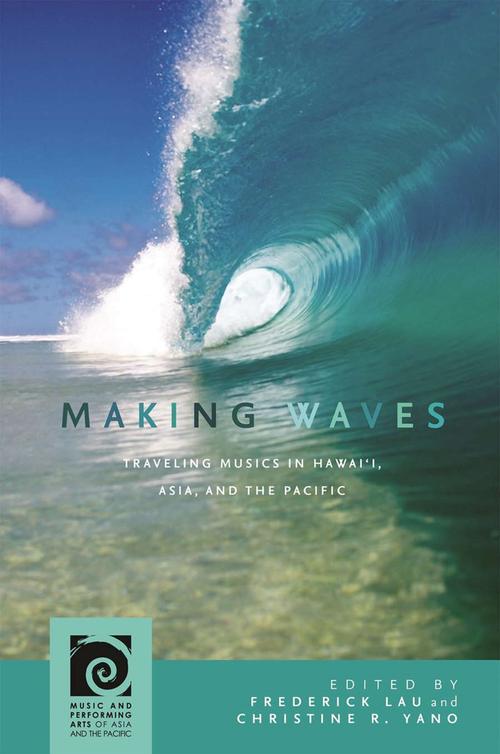

Sounding WavesIntroduction

Christine R. Yano and Frederick Lau

M usical sounds are some of the most mobile and malleable of human elements, crossing national, cultural, and regional boundaries at warp speed in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Whole songs or even bits of songs travel long distances via musicians, CDs (and earlier, cassettes), satellite broadcasting, digital downloads, and streaming. They become part of global human flows, enabled through ideologies and technologies of circulation, shaped by the infrastructures of movement. And in the process they become transformedwarped, bent, tweaked, twanged, electrified, digitized, ornamented, indigenized, performed on makeshift instruments. Traveling musics may be interpreted as mis-heard, mis-read, mis-sung, mis-remembered. This is not to suggest a single correct way to hear, read, sing, and remember. But it is to suggest that the idea of correctness in the name of authenticity may suffuse these processes of traveling and the hegemonies that litter that path. It also suggests the ways in which traveling musics lead multiple lives of hearing, reading, singing, and remembering, as well as the unintentional consequences of the practices of contact. They may act as basis for innovative renderings in new hands, so that the mis- processes identified above take on varying degrees of creative intentionality. At the same time, in new contexts traveling musics may take on new meanings, suggesting nostalgized sounds of home, and thus become emblematized and codified. They become badges of identity. In new contexts, these sounds incite, seduce, and sometimes repulse. They may be music overheard by eager ears or music barely heard over the cacophony of competing sonic backdrops. Some arrive on distant shores folded into the baggage of colonialism or missionization, flaunting prestige or salvation like a banner of entitlement. Others arrive as stowaways, sung in subterfuge as whispered sounds of illicit engagement, resistance, and sometimes salve. Songs can soothe and motivate as the sound of the familiar amid arduously traveled lives.

As musics in motion become intimate parts of human encounters often thousands of miles from their original settings, they inevitably undergo transformations in meaning and context. Traveling musics undergo change even as they effect change in new settings. Listeners take heed, their ears primed by sociopolitical conditions, and that heed may result in new creations and selective borrowingsa melodic turn, a rhythmic pattern, a vocal quality, an instrumental timbre. These borrowed elements become the basis for newly reconfigured sonic expressions and creativity. In some cases this kind of borrowing may symbolize or even encourage cross-cultural understanding; in others the impetus may simply arise from an attraction to novelty as a fresh sound, an aural prompt. By tracking how music travels, we are also interested in identifying the agencies, dynamics, circumstances, and processes that make each journey possible. There is always a backstory behind each movement. Together we demonstrate that any piece of music or an instrument can become resources that enable social actors to construct, shape, and imagine appropriate meanings for the context. In other words, music is at once a sign vehicle pregnant with significance and symbolism as a possible agent for creative impulses and marking boundaries.

This volume of essays by veteran ethnomusicologists examines traveling musics in Asia and the Pacific as integral to sociopolitical practices of mobility. We look at musicssongs, makers, groupings, performance practices, instruments, audiences, aurality, aesthetics, and imagesas they traverse oceans, continents, and islands. In the process of landing in new homes, music interacts with older established cultural environments, sometimes in unexpected ways and with surprising results. We see these traveling musics in Asia and the Pacific as making wavesthat is, not only riding flows of globalism and migration, but also instigating ripples of change and generating new possibilities. We ask, what is the nature of those waves? What are the infrastructural elements that constitute the wave itself? What are some of the effects of music landing on, transported to, or appropriated from distant shores, and what kinds of responsibilities lie in the process? And furthermore, how does the Asia-Pacific context itself shape and get shaped by these musical waves and their effects? How might we reconfigure our practices and reflections upon listening by refocusing from the solidity of land masses to the fluidity of ocean environments? What might be gained in the process by accepting the indeterminacy of wavesthe rogue wave amid a generally perceived orderly backdrop? The goal of this volume is to position music as at once ritual and entertainment, esoteric and exoteric, product and very much process, sources of tradition and creativity, local and very much global, within the cultural geopolitics of Asia and the Pacific. In doing so, we situate music at the very core of global human endeavors.