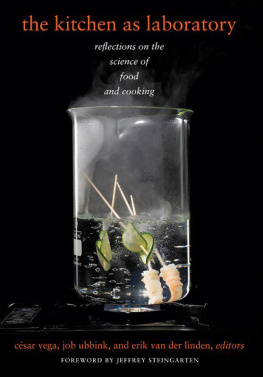

the kitchen as laboratory

arts and traditions of the table: perspectives on culinary history

the kitchen as laboratory

reflections on the science of food and cooking

Edited by

Csar Vega, Job Ubbink, and Erik van der Linden

Foreword by Jeffrey Steingarten

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2012 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN: 978-0-231-52692-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The kitchen as laboratory : reflections on the science of food and cooking / edited by Csar Vega, Job Ubbink, and Erik van der Linden.

p. cm. (Arts and traditions of the table)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-15344-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. FoodAnalysis. 2. FoodComposition. 3. Cooking. I. Vega, Csar. II. Ubbink, Job. III. Linden, Erik van der.

TX541.K55 2012

664.07dc23

2011029237

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to her about your reading experience with this e-book at cup-ebook@columbia.edu.

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the editors nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

The use of recipes, preparation of food, testing of scientific concepts, and application of techniques described in this book must be done by only qualified people, and all possible safety precautions should be followed.

JEFFREY STEINGARTEN

Are we in the midst of a culinary revolution? Will cooking ever be the same? The answers are, respectively, yes and no. But what kind of revolution is this anyway? We cannot even agree on its name. We do not know who started it or when. And we do not know where it is heading or what the world will be like when it has run its course.

The previous revolution was launched in 1972 by Henri Gault, a French journalist and critic. In an article, he called it nouvelle cuisine and the name stuck, although by todays sophisticated branding standards, it was too general, ambiguous, unspecific, and bland. The term nouvelle cuisine, however, took off like a rocket and, as far as I know, was never seriously challenged except by people who challenge everything and those who considered the cuisine unrevolutionary and not nouvelle enough. French chefs at least as far back as Franois Pierre La Varenne in the seventeenth century have claimed to be revolutionizing French cooking through a process of simplification and purification. In 1973, in Vive la nouvelle cuisine franaise, Gault and fellow critic Christian Millau issued the Ten Commandments of nouvelle cuisine, of which only some specified a new way to think about food; one commandment, for example, recommended introducing air-conditioning into restaurant kitchens. But when a journalist aims for a catchy list of ten or twenty items, he or she must often pad the list to reach the magic number.

Gault and Millau were, in essence, reporting on how prominent young chefs were actually cooking in a new way. But a renewal of sorts had been bubbling through the old style of French haute cuisine in, for example, the cooking of the great Fernand Point. At La Pyramid, his restaurant in Valence, which he opened shortly after World War I, he trained chefs later associated with the nouvelle cuisine, particularly Paul Bocuse, Michel Gurard, and Alain Chapel. What made the young generations approach to cooking and food presentation a revolution was simply that a journalist called it a revolution and gave it a catchy title.

The problem is that the name of the current gastronomic revolution was coined by scientists instead of journalists, a mortal error. Nonetheless, the term they first produced, molecular gastronomy, was perfectly fine. For an appellation to be perfect, I suppose, it must include everything it names and exclude everything it does not. But names are rarely perfect. By this standard, the term molecular gastronomy is no worse than, say, the titles As You Like It and Alls Well That Ends Well, which indicate nothing about the story lines of the plays. Molecular gastronomy is a metaphor or, really, a metonymy. When my wife, Caron, was learning Mandarin in graduate school, she informed me that the modern Chinese word for a ballpoint pen is yuan zi bi, which means atomic pen. Now, do the Chinese people believe that there is a nuclear bomb inside each pen or that the ballpoint pen represents a novel exploitation of the atom? Of course not. For them, at that remote time when the ballpoint pen thrilled them with its novelty, atomic seemed the perfect word to express the idea of futuristic. Maybe we should call the current revolution atomic gastronomy.

In this handsome book, the editors suggest that we refer to this movement as science-based cooking. This term, however, reveals nothing about what went on in restaurants such as Ferran Adris El Bulli, where I had my first meal in 1998. What impressed me most about this meal was a plate arrangement that had the main ingredient in the center, enclosed in a circle of other ingredients, one of which was the inside of a tomatothe gel and seeds that French cookbooks have you squeeze out and discard from the start, but here presented intact. A day or two later, I asked Ferran how he had accomplished this, and he showed me, holding a long plum tomato in one hand and a knife in the other. After slicing off the top of the tomato, he ran the knife down the outside of the flesh (pericarp) wherever it was supported by one of four internal ribs (septa), cutting through each rib. The result was six or eight sections of tomato flesh that he pulled away, revealing four compartments (locular cavities) packed with gel and seeds that he removed, intact, with a spoon. Nobody else of whom I am aware has ever handled a tomato like this. (If you follow Adris method to separate the inside from the outside of a raw tomato and taste both, you will learn that the stunning umami flavor of the tomato lies mainly in the seeds and gel, as was later demonstrated by Heston Blumenthal.) Things change when you cook the tomato. Another example is Ferrans cauliflower couscous, which is created with a sharp, thin knife in one hand and a cauliflower floret in the other, held over a sheet of waxed paper. When you peel off the outer inch or slightly more of the cauliflower, it falls onto the paper in tiny white balls that resemble couscous. Great amusement ensues as the diners discover the delicious trick that has been played on them.

There is nothing strictly scientific about it. Harold McGee prefers the phrase experimental cuisine. I like that term, too, because it is inclusive, and I believe that it implies a systematic series of hypotheses and trials. The techniques for separating the tomato and shaving the cauliflower were, as far as I can tell, unprecedentedbut not quintessentially scientific. Both depend on the close observation of natural forms, the province of either biologists or painters and engravers.

When did it all begin? A crucial moment came in 1974 when French chef Pierre Troisgros asked fellow chef Georges Pralus to figure out how he could cook his foie gras terrine without losing the typical 30 to 50 percent of its weight. Pralus turned the industrial method of sous vide cooking to gastronomic ends, wrapping the terrine in plastic and immersing it in hot water that was maintained at a moderate temperature. And when it was done, the terrine had lost only 5 percent of its weight. History was made! Profits soared! Nearly all of the foie grass fat was kept in the terrine, still integrated with the liver, so the calorie count in each serving size must have soared. I wonder if anybody bothered to notice this.