RACHEL RODDY

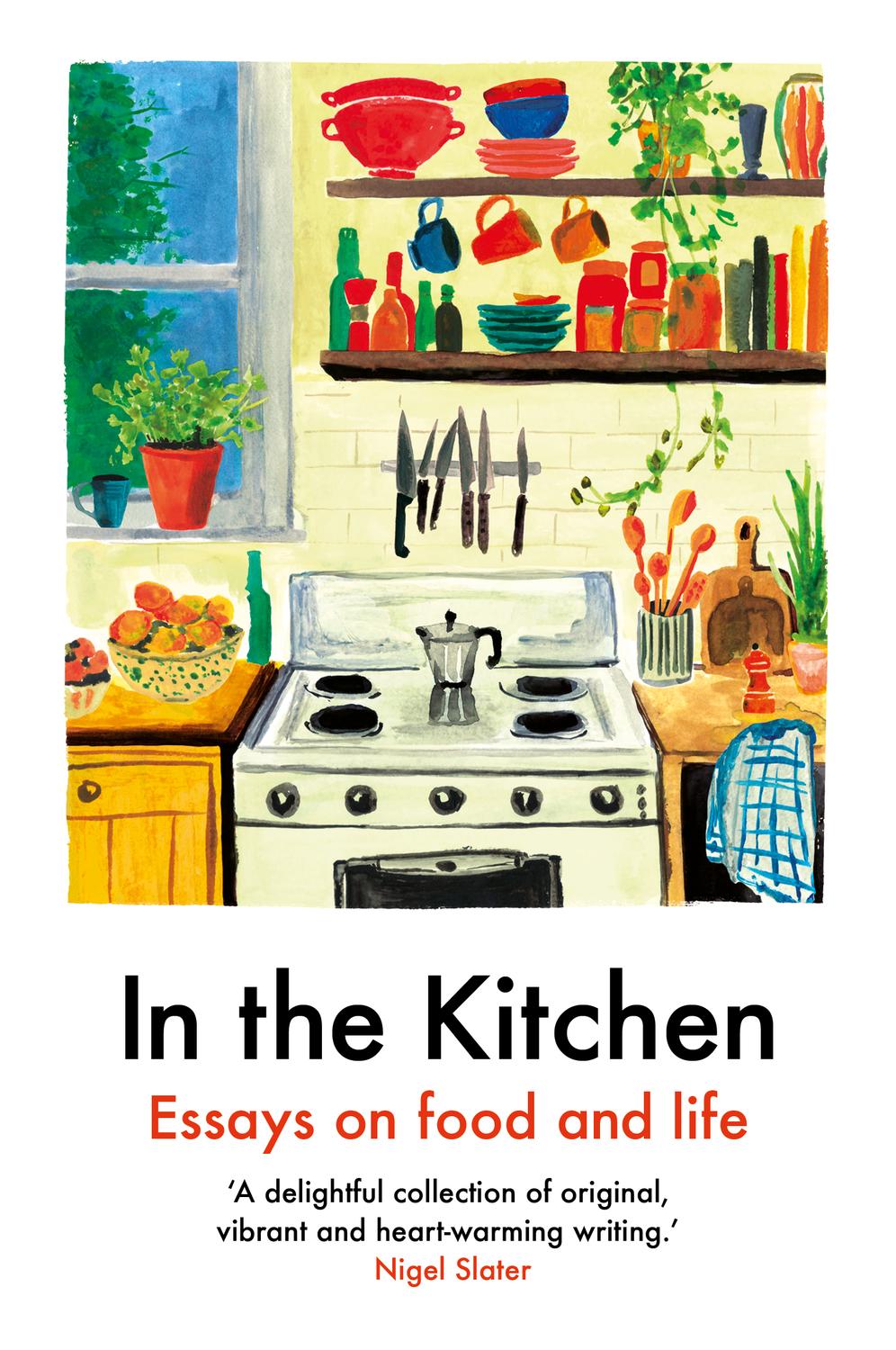

Gasfire cookers are not just heavy, theyre awkward. This one was a smooth, white box with nothing for us to hold onto except the sharp bottom edges. It was an ordeal getting it up the stairs to our flat, our inability to cooperate exposed by a kitchen appliance. For two days it sat in the middle of the kitchen, disconnected and in the way. On the third day an authorised man came and for 90 euros talked about the risks of buying secondhand appliances while fitting a new green tube between the Gasfire and the mains. It was alive! As he tested each burner and knob, sending pantomime-villain hisses of gas into the air, he told us it was a model from the late 1960s, one of the last to be made entirely by hand, vintage, therefore much in demand. I took this (along with the fact he had gone ahead and connected it) as reassurance, despite a lingering smell of the gas that could at any moment ignite, explode and kill us. Once hed gone I opened all the windows, wiped his oily fingerprints from the white enamel, put a pan of water on for pasta and made a slutty sauce of tomatoes, olives, capers and anchovies. Then while one pan trundled and the other spat, I admired my twentieth cooker.

Going right back to the beginning, I have no recollection of the first cooker in my life, or rather my parents cooker in their house in a town called Lymington. Mums recollection is vague, only that it was an inherited gas cooker with an eye-level canopy grill used for cheese on toast, bacon, and lamb chops. Now Im a mother myself, the need to understand and label a childs appetite is familiar, as if to do so is to understand them, therefore protect them. I was never fussy or picky rather a good feeder and a good little eater, banging my fists for a baby food called Farex. Dads photograph of me in Mums arms on a beach in 1973 seems evidence of this, the collar of her white flannel shirt poking over her red jumper, my hand on her plum-sized silver locket and my cheeks so plump they look as if they might pop.

Photographs act as jump leads for memories; I have two images of the second cooker. It was an Aga, the blood red, 406kg, cast-iron reason my parents moved 130 miles north and bought their next house. Nowadays large ovens are familiar, like wide televisions and great flapping fridges, but in 1976 the Aga seemed enormous, swollen, almost too big for the kitchen. Designed by the Swedish physicist Gustaf Daln in 1922, the Aga is a heat storage cooker which works on the principle that its cast-iron body absorbs heat from a low intensity source and the accumulated heat can then be used for cooking. This accumulated heat means the Aga is always hot, always working (although clearly not by itself) not just as a cooker, but as a clothes dryer and press, water heater and radiator. It was also a prop. My four-foot memory of that Aga is as a heavyweight comforter, of adults putting their arms behind their back, looping their hands over the bar and rubbing their bottoms against the hot front surface.

Soon everything was swelling: us kids, the GDP, my dads business. The Aga didnt move with us, so for a while the big new kitchen, with its inherited Viking ship-like shelves sailing down the middle, didnt have a bum warmer. It had a Hotpoint electric cooker (the third) with a Perspex splashback and a scratched history from the previous family, evidence of their hundreds of meals concentrated into rings of treacle-like residue round each knob. On the hardworking Hotpoint, Mum cooked an incessant and reassuring rota of roast chicken, shepherds pie, Bolognese sauce, tomato sauce, fish fingers, baked potatoes, sausages, buttered peas, Jane Grigsons leek and potato soup and Elizabeth Davids ratatouille, all of which steamed up the windows and the lenses of my pink NHS specs, and sustained our unit of five.

The fourth cooker arrived when I was ten, another Aga replacing the tired Hotpoint, this time installed under a red brick arch, which made it look really rather prosperous. Cooking became even more purposeful and the kitchen even warmer. On Friday nights we listened to Queen or Fleetwood Macs Tusk and danced like wild things while Mum cooked, until Dad put his hands on her waist and got her to dance too. By now I loved helping, drawing figures of eights in white sauce, or pulling on the massive oven glove, lifting a hot, heavy door up and off its latch to open it, pushing potatoes impaled on the four-pronged spike in, then hooking the door closed again. Aga ovens are twice as deep as they are wide, a dark tunnel for a small arm and mind after all, the witch does choose a stove in which to imprison the prince. One day, while trying to retrieve something, my arm met the bars of a shelf in the hottest oven. I yanked it out to find it looked like a lamb chop lifted from a griddle, branded with three short and angry pink lines. My integrated worry about getting things wrong meant I didnt tell anyone, or get half a raw potato to hold onto the pain; instead I pulled my sleeve down and pressed, pressing my school jumper into the burns, where the wool stuck. Eventually it eased away, leaving behind tiny green threads of my mistake that when I did tell her what had happened my mum picked out gently with tweezers.

While I am only including cookers from places I called home (which puts paid to vanity cookers and one-night stands), there are others that need mentioning. The cream and green electric cooker with hot plates like liquorice whirls in my grandma and grandpas kitchen in Stokesley in North Yorkshire. Steadfast and reliable, the cooker seemed an extension of my grandma and was where she boiled tongue for hours and made pan after pan of a minced beef and potato stew called tattie hash, the smell of which clung to the wallpaper like a pattern, along with worry and love. When they moved down south to be near us, Grandma continued to make tattie hash on an Electrolux electric cooker.

Another was in the kitchen of my other grannys pub, the Gardeners Arms at Mill Bottom in Oldham. Like the Victorian pub itself, with its atmosphere dense with the smell of bitter, smoke, Brasso and loose words, the industrial cooker, with its noisy flames and big knobs, was thrilling and a bit frightening. It was positioned near the kitchen door that passed into the back darts room, so standing at the burners you could hear the soft dooof of sharp points meeting the board, the cheers and groans. My great-aunt was usually in charge, cleaning up mess before it was even made, frying thin steaks or bacon to put in white rolls with floury tops called oven-bottom cakes, or lifting baskets of chips out of boiling fat, then serving my uncle and my brother first, because they were boys and more important. Food was passed from the cooker through a rectangular hatch into the low-lit bar where it was eaten by men mostly cotton mill workers, dry stone wallers and electricians on high stools nursing dimpled mugs of amber Robinsons Bitter. Sometimes we would sit up at the curved bar too, eating chips and sucking lemonade through straws, wiping our greasy fingers on our trousers and swinging our legs in time to Bob Seger singing about Hollywood nights, how she was looking so right, in those diamonds and frills. From those stools everything looked so right.

Back home, the swelling continued and the Aga was traded in for an even bigger model (the fifth). Like insulating foam expanding to fill an available space, family cooking filled the two new ovens. It was the same rota of tomato sauce and roasts with puffs of Yorkshire pudding, of lamb chops topped with slices of potato, just more of it. And hummus, bowl after bowl of manila-envelope-coloured hummus. How had we lived without it? Four permanently hot ovens meant there was an even greater chance of forgetting you had put something inside (a cake, a prince, a secret?). Potatoes bowled-in on Tuesday were like charcoal when found on Thursday, while overnight rice pudding left far too long soldered itself to the dish like Japanese lacquer. More space also meant more room for bums. The Aga was a magnet and an anchor, regardless of how much we grew and thrashed, and in those years it held us, tighter when my grandpa died, tighter still when my twenty-one-year-old uncle fell asleep in the car in the garage, with the engine running. Surely no one else could go adrift?