To Patagoniathe land of my childhood, the land that inspired my life.

Fire has its own language, spoken in the realm of heat, hunger, and desire.

It speaks of alchemy, mystery, and, above all, possibility.

It comes from a time long before I can recall.

A Son of the Andes

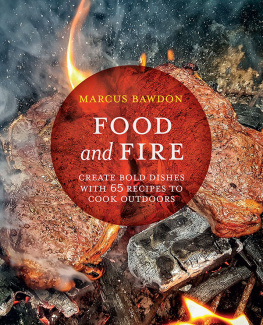

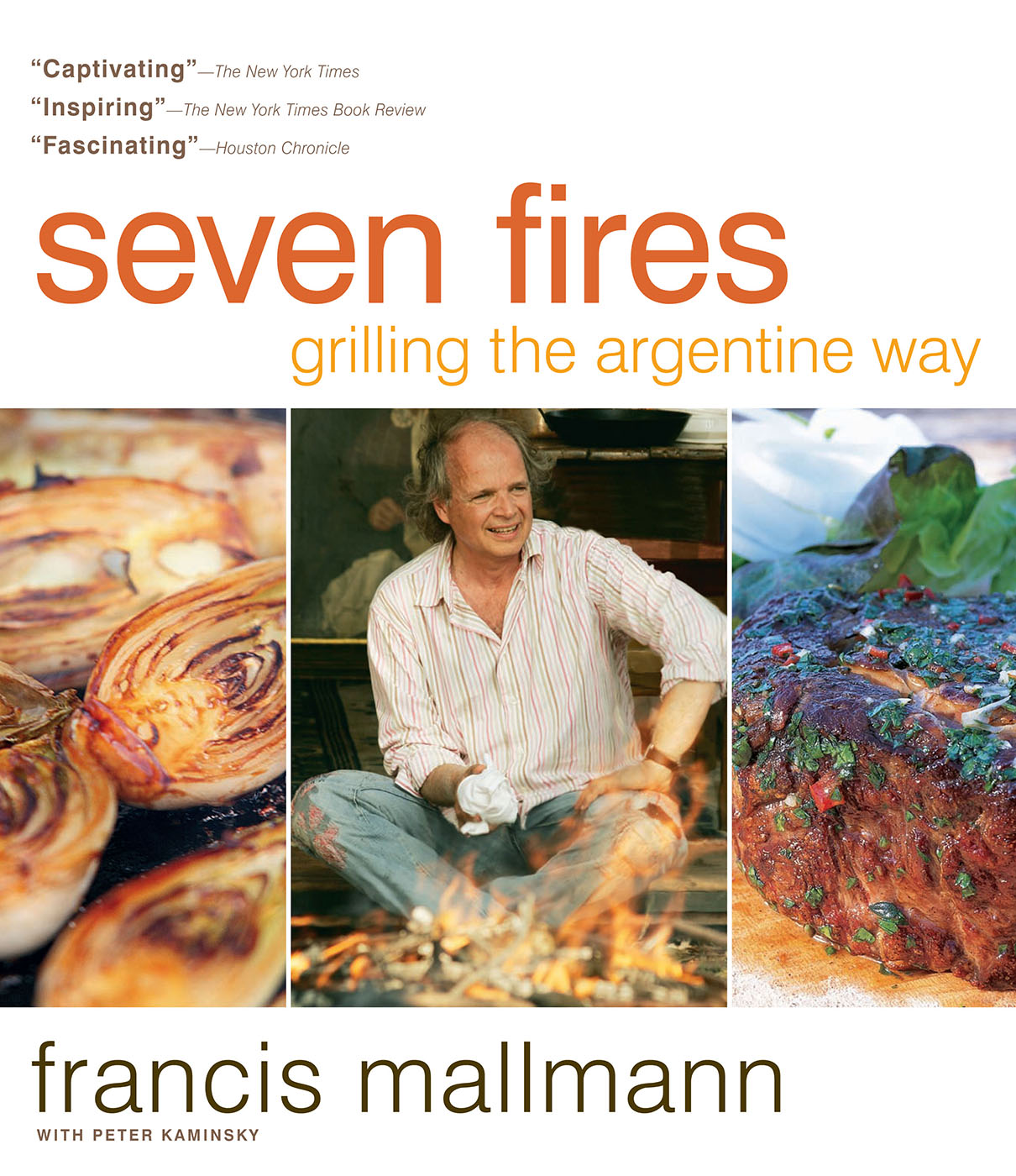

The idea for this book grew out of a television series that Francis Mallmann made a few years ago, Fires of the South. He went on location in the wilds of wintry Patagonia to present the many varieties of wood-fire cookery. As youll see, it is simple cooking, but at the same time truly inspired. Youll never taste a more succulent steak or a heartier winter stew.Youll discover that every fire has its own life and that from first spark to leaping flameto smoldering ember, all the alchemy of combustion can be used to make great food. You may, as I have, come to rethink whatever opinion you had of barbecuing and grilling. In Franciss hands, the grill produces world-class gastronomy (a word that makes him cringe but which seems quite apt to me).

Francis is South Americas most famous chef, a distinction helped in part by his movie-star looks and long-running career as the reigning star of food TV in the Spanish-speaking world. Hes also a man of immense, highly personal style, but it is his skill and inspiration as a chef that remain the basis of his success and his fame.

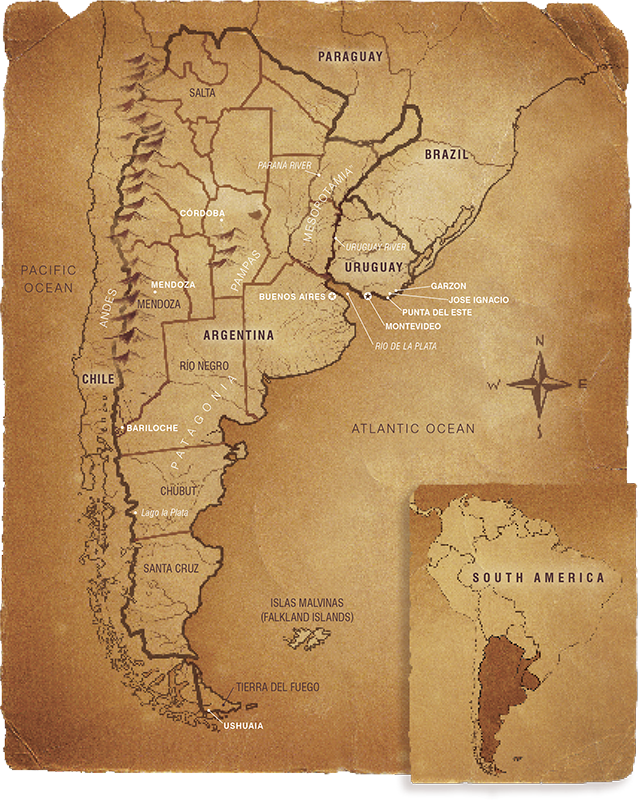

Raised in the mountain town of Bariloche, the son of the nations preeminent nuclear physicist, Francis was too high-spirited for his strict English-language boarding school. He spent the better part of his early adolescence on the nearby ski slopes and then took off for California, where he worked as a carpenter and street musician.

When he returned to Argentina two years later at the age of nineteen, he opened a restaurant in Bariloche. His innate kitchen talent and his suave front-of-the-house manner soon earned him a loyal following and his career took off. Within a few years, he had the opportunity to open a small restaurant in a tiny village about thirty miles up the coast from the jet-set resort of Punta del Este, Uruguay. Fashionable Argentines spend weekends and summers here, just as New Yorkers flock to the Hamptons.

With the money he made during the holiday season in Uruguay, Francis could afford to close down when the vacationers left and intern in some of the most illustrious kitchens in France. Notable among them were those of Roger Verg and Alain Senderens, which had six Michelin stars between them.

With that experience as his calling card and his subsequent success as a chef on Argentine television, Francis was soon the toast of Buenos Aires, but by the time he was forty, he was, in his words, tired of making French food for wealthy Argentines. He wanted something else, something more fundamental and yet refined. The result was an evolving cuisine that he called Nuevo Andean, based on the wood-fire and cast-iron cooking practiced by generations of gauchos and Native Americans.

This is not to say that Francis jettisoned all the techniques of classic French cuisine that he had learned. Like any good French chef, he is a master of the art of intensifying, deepening, and developing all the flavors and textures of his ingredients. But rather than rely on complex sauces and architectural presentations, he keeps it simple. His list of ingredients for any recipe is usually short, the number of steps are few and simple. What makes his recipes so compelling is his mastery of wood fire.

A corollary of his return to his Andean roots was a nearly complete abandonment of the slow-cooked stocks and sauces canonized by Carme and Escoffier. In fact, in the dozen years I have known Francis, I dont believe Ive ever seen a stockpot in his kitchen (although he has told me that he uses them occasionally). In place of classic sauces, he often dresses his food with olive oil and herb mixtures, adding vinegar or lemon juice for brightness.

Although simple cooking and gaucho rusticity were at the heart of his evolving style from the beginning, he set his table with white damask place mats and napkins from the artisanal looms of Le Jacquard Franais in Paris and faience from Astard du Villete in Provence. His steak knives were handcrafted with wide shafts, long sharp points, and handles made of huayacan, a prized hardwood that grows on the slopes of Mount Tupungato, in the wine country of Mendoza.

It is now a dozen years ago since my friend Dana Cowin, the editor of Food & Wine magazine, asked if I would be interested in writing the text to accompany photographs taken at Franciss Patagonian lake house. She thought my fluency in Spanish would make the interview go more smoothly. But she neednt have concerned herself about that; Franciss accent was more British than Argentine and his English was thoroughly modern American. More Bob Dylan than Dylan Thomas.

Thus began a friendship between my family and his. There have been late-night dinners at his restaurant in La Bocathe Buenos Aires neighborhood where the tango was borncar treks the length of Patagonia, Christmases in Brooklyn, and Easters in Uruguay.

By this time, we are two members of a large family. This book, of Franciss recipes, is our invitation to you to join the family. Whether you cook these recipes over a campfire, on your backyard grill, or in your home kitchen, may you beas we areinspired by fire.

PETER KAMINSKY

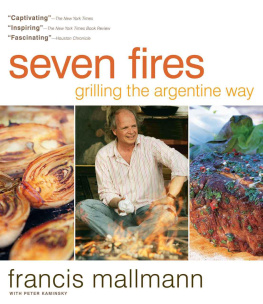

Francis Mallmann and Peter Kaminsky in Garzon, Uruguay.

Baptized by Fire

In the farthest reaches of the Andes, in the depths of the Valdivian alpine rain forest, I light a fire when I arrive and never let it go out until the moment I leave.

My childhood home stood on a cliff overlooking Lago Moreno in Patagonia, where the snowcapped peaks of the Andes tower over everything. It was a simple but beautiful log house built by an English family in the 1920s and bought for my father by Papapa, my grandfather Arturo. In that house, fire was a constant part of growing up for my two brothers and me, and the memories of that home continue to define me.