MALLMANN ON FIRE

FRANCIS MALLMANN

with Peter Kaminsky and Donna Gelb

PRINCIPAL PHOTOGRAPHY BY SANTIAGO SOTO MONLLOR

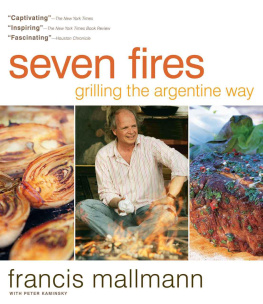

Also by Francis Mallmann

Seven Fires

Title page: Mendoza at twilight with the vineyards and the Andes in the distance.

Copyright 2014 by Francis Mallmann

For photography credits, see , which is an extension of this copyright page.

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproducedmechanically, electronically, or by any other means, including photocopyingwithout written permission of the publisher.

Published by Artisan

A division of Workman Publishing Company, Inc.

225 Varick Street

New York, NY 10014-4381

artisanbooks.com

Published simultaneously in Canada by Thomas Allen & Son, Limited.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN 978-1-57965-644-7

Get Up and Get Out

Some years ago, it struck me how settled in our ways we have all become. Our evenings take us from the office to the couch, from the couch to the kitchen, from the kitchen to the easy chair by the television, and from the easy chair to bed. I realized that for most people, the mere thought of grabbing a basket packed with a picnic and thinking of an outdoor space to enjoy was just that... only a thought.

So I decided to make a TV show to prompt them out into the wild. It would be based on the simplest recipes, requiring barely any equipment. I began the first show by putting on my favorite tweed jacket, a hat, and some walking boots. I put a potato in my left pocket and a tin cup with two eggs in my right pocket, along with a metal spoon, salt, pepper, and a chunk of butter wrapped in paper. I held an onion in my hand and, instead of an Herms handkerchief, I stuck a handful of fresh parsley in the top pocket of my jacket.

Then I walked into the hills until I got to a nice stream, where I started piling up fallen branches to start my fire. From the streambed, I selected a large, flat gray stone with a slight hollow in the middle, just like a soup plate. I still remember looking through the clear running water, searching for just the right stone. How many years had this one been there, I wondered. Maybe it had been tossed up by a volcano and then worn smooth by the caress of snowmelt.

I propped up my cooking stone on two rocks set on either side of the fire and let it warm up. Stones, especially those from a stream, must be heated very slowly for cooking to prevent them from cracking or bursting apart, as any water trapped within turns to steam, eager to escape.

I took the small outdoorsmans knife that always hangs from my belt on my country walks, set the onion on my knee, and chopped it, dampening my jeans in the process. I tossed the diced onions in butter, which Id melted in the bowl of the stone. I cut the potato into thin round slices and added them to the onion. After about forty minutes of sizzling, they were cooked to tenderness. That was the moment to crack the eggs and fold them in with my spoon. I tore the parsley apart and threw it in as well. Salt, pepper, and an extra pat of butter finished my lunch, with some chilled water from the stream served in my tin cup. Using a nearby log as table and chair, I thoroughly enjoyed the lunch that launched seven seasons of cooking on TV.

My advice to you: turn the off television and go outside.

CONTENTS

BY PETER KAMINSKY

TRAVELS WITH FIRE

PARIS, FRANCE

TRAVELS WITH FIRE

LA RUTA AZUL, PATAGONIA

TRAVELS WITH FIRE

TRANCOSO, BRAZIL

TRAVELS WITH FIRE

THE ISLAND, PATAGONIA

ON TOP OF THE WORLD

BY PETER KAMINSKY

Francis Mallmann views food as he does almost everything else, as an aesthetic expression. So, yes, the dining is unforgettable, but to this native of Patagonia, food is the melody in a larger symphony of pleasure. Almost as important are the setting, the plates, the linens, the scenery, the music, and the books that he sometimes uses instead of place cards (this morning, my table on the patio of his small hotel in the village of Garzn was reserved with a volume of Rilkes poetry).

As I reflect on my twenty years in Mallmann Landwhich my wife refers to as The Realm of the SensesIm sitting on a green hill overlooking a broad valley: a vista of forests, fields, vineyards, and olive groves. The warm breeze rising off the valley floor is soft and sweet.

Around my perch, a platoon of workers has been deployedsome with bright head scarves and tattoos that would not look out of place on a pirate frigate. They lug enormous iron implements and place them along the ridge. The shapes and rusty orange color call to mind the sculptures of Richard Serra.

This iron, though, is an expression of a different artwood-fired cooking. There is a huge cauldron that will be filled with lard for frying empanadas stuffed with fatty beef, olives, and eggs, in the style of Salta, in the north of Argentina. It was in this provincepeopled by Incas and the descendants of Canary Islandersthat Francis, in his twenties, first encountered the seven fires that would redefine the oeuvre of this classically trained chef and lead him to devote his career to restoring wood-fired cooking to a place of honor in the world of big-league cuisine.

In addition to the cauldron, there is a huge chapa, or plancha, that takes eight people to muscle into position. To its left, several men carry a parrilla unlike any barbecue grate I have ever seen. It looks like an old iron box spring as seen in a fun-house mirror, higher on one end and sloping down to shorter legs. Also, as at many of Franciss big productions, there is an infiernilloliteral translation, little hellan Inca-inspired device of his own invention where a tray with a salt-crusted whole fish is sandwiched between two cast-iron platforms, each with its own roaring fire. In full blaze, it conjures up a brace of funeral pyres for a couple of fallen Vikings.

Farther up the hill, a ring of ironfour inches thick and five feet in diameteris muscled into place. It is not a complete circle: one end is open so that the radiant heat of a bonfire can slowly cook two lambs that are placed on iron crosses about six feet from the circle of fire.

Overlooking all this iron, there are three wooden platforms of weathered timber. Tall pieces of lumber reach up from the corners of each platform, like the bedposts of a canopy bed. They serve no apparent purpose other than to mark off a space that, while it is completely open to the air, somehow feels enclosed.

Francis, in tattered jeans, white shirt with sleeves partly rolled, and sunglasses, sits at one of the tables, displaying a wide smile.

Looking again at the assemblage of wood and iron in the last rays of sunlight, I reflect that an archaeologist might be excused for thinking that he had come upon the ceremonial precinct of a past civilization.

Next page