ALSO AVAILABLE IN LAUREL-LEAF BOOKS:

THE HERMIT THRUSH SINGS, Susan Butler

BURNING UP, Caroline B. Cooney

ONE THOUSAND PAPER CRANES, Takayuki Ishii

WHO ARE YOU?, Joan Lowery Nixon

HALINKA, Mirjam Pressler

TIME ENOUGH FOR DRUMS, Ann Rinaldi

CHECKERS, John Marsden

NOBODY ELSE HAS TO KNOW, Ingrid Tomey

TIES THAT BIND, TIES THAT BREAK, Lensey Namioka

CONDITIONS OF LOVE, Ruth Pennebaker

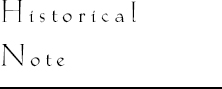

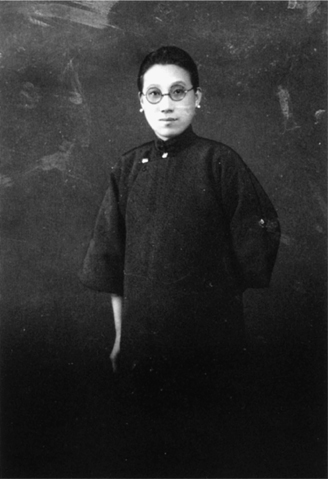

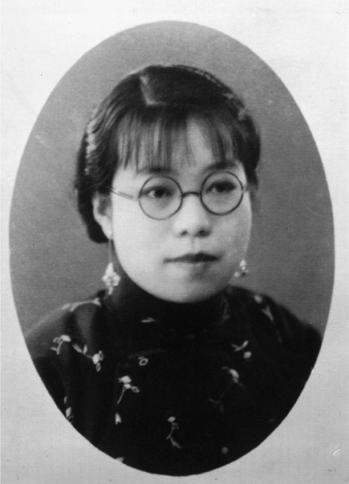

My grandaunt was also known as Gong Gong (Grand Uncle) because of the respect granted her as president of the Shanghai Womens Bank, which she founded in 1924. As a child of three, she refused to have her feet bound. She attended a missionary school founded by American Methodists and was fluent in English. Her bank at 480 Nanjing Lu in Shanghai is still in operation.

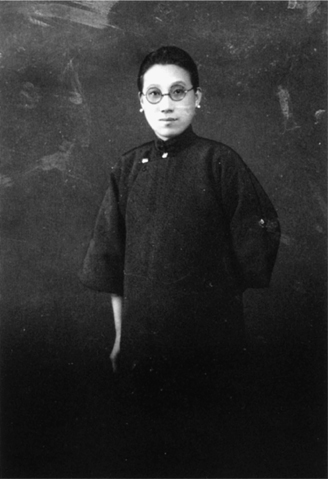

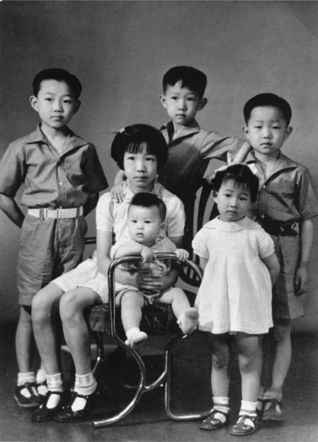

My brothers and sisters. Back row, from left: Gregory, James, Edgar. Front row, from left: Lydia with baby half sister Susan, and Adeline. This picture was taken in Tianjin in 1942 before the death of our grandmother. We were all fashionably dressed in Western clothes and had stylish haircuts.

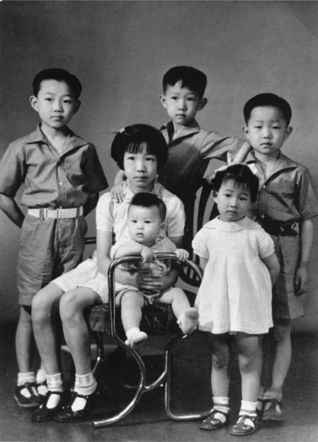

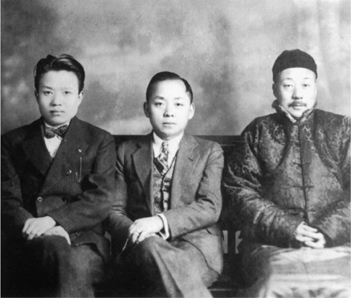

The boom days of Tianjin provided economic opportunities for Ye Ye, my grandfather, on right; his son, my father, at left; and K. C. Li, at the center. K.C. was one of the first Chinese graduates of the London School of Economics and the founder of Hwa Chong Hong, a highly successful import-export firm. Both my grandfather and my father worked for him.

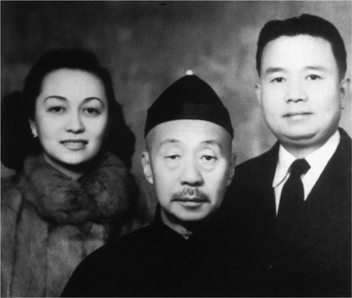

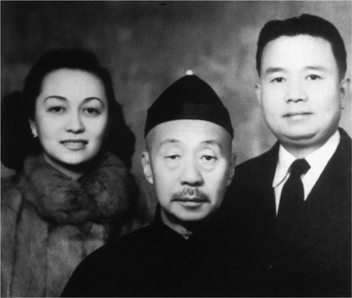

My stepmother, Niang (Mother), and my father with Ye Ye (middle) in the 1940s. Ye Ye was a devout Buddhist. He always shaved his head, wore a skullcap in winter, and dressed in Chinese robes.

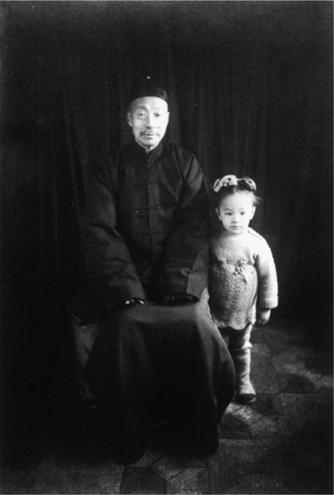

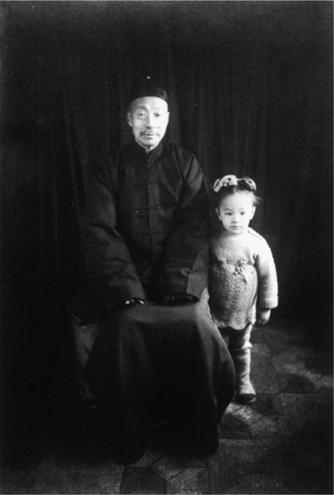

Ye Ye and my baby half sister, Susan. The picture was taken one and a half years after their arrival in Shanghai from Tianjin in October 1943.

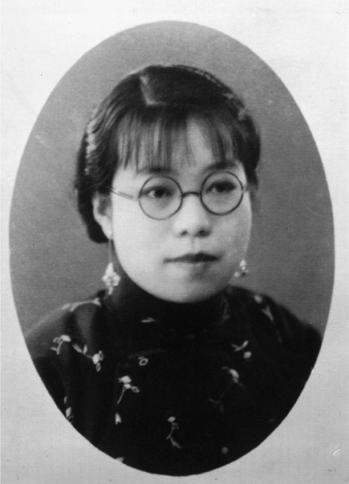

Aunt Baba never ceased to nurture me as a child, praising my accomplishments in school, checking my homework, and sharing her pedicabs with me. She never married and was financially dependent on my father and stepmother all her life. She was gentle, patient, and wise. I loved her very much.

On page 200 is the Chinese text of a story from China written during the Tang Dynasty (618906 A.D.). It is the story of Ye Xian,  , also known as the original Chinese Cinderella. Isnt it mind-boggling to think that this well-loved fairy tale was already known more than one thousand years ago? My Aunt Baba told me about Ye Xian when I was fourteen years old. You too can read all about Ye Xian in Chapter 22.

, also known as the original Chinese Cinderella. Isnt it mind-boggling to think that this well-loved fairy tale was already known more than one thousand years ago? My Aunt Baba told me about Ye Xian when I was fourteen years old. You too can read all about Ye Xian in Chapter 22.

I am grateful to Feelie Lee, Ph.D., and Professor David Schaberg of UCLAs East Asian Languages and Culture Department for their scholarship and research in finding the book You Yang Za Zu at UCLAs East Asian Library. You Yang Za Zu contains a miscellany of ninth-century Chinese folk tales, among which was the Chinese text of Ye Xians story. The author was Duan Cheng-shi ( ), whose stories were collected in an encyclopedic book that went through many editions during the last eleven hundred years.

), whose stories were collected in an encyclopedic book that went through many editions during the last eleven hundred years.

Please note the absence of punctuation and the beautiful Chinese characters, almost as if each word had been painted with a brush. This was how ancient Chinese texts were written. The oldest Chinese books were copied by hand. However, this particular reissue was probably block-printed.

For many years, the story of Cinderella was thought to have been invented in Italy in 1634. Iona and Peter Opie in The Classic Fairy Tales, published by Oxford University Press in 1974, consider the Italian Cinderella story the oldest European version. We now realize that Duan Cheng-shis Ye Xian predates the Italian tale by eight hundred years. Cinderella seemed to have traveled to Europe from China. Perhaps Marco Polo brought her eight hundred years ago from Beijing to Venice. Who knows?

China is a big country, roughly the size of the United States. It has the worlds oldest continuous civilization, and Chinese writing has remained virtually unchanged for the past three thousand years. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, China was the most powerful country in Asia. The country looked inward and considered itself the center of the world, calling itself zhong guo, which means central country.

In 1842, China lost the Opium War. As a result, Britain took over Hong Kong and Kowloon. For about a hundred years afterward, China suffered many humiliating defeats at the hands of all the major industrial powers, including Britain, France and Japan. Many port cities on Chinas coast (such as Tianjin and Shanghai) fell under foreign control. Native Chinese were ruled by foreigners and lived as second-class citizens in their own cities.

In 1911, there was a revolution and the imperial Manchu court in Beijing was abolished. Sun Yat-sen became president and proclaimed China a republic. However, the country broke into fiefdoms ruled by warlords who fought each other for control of China. Chiang Kai-shek, a military general and protg of Sun Yat-sen, took over after Suns death in 1925.

Japan first seized Taiwan from China in 1895. It then usurped Manchuria. In July 1937, Japan declared war on China and quickly occupied Beijing and Tianjin.

When I was born in November 1937 in Tianjin, the city was still divided into foreign concessions. However, outside the concessions, the Japanese were in charge. My family lived in the French concession, where we were ruled by French citizens according to French law. My sister and I attended a French missionary school and were taught by French Catholic nuns.

On December 7, 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and declared war on the United States and Britain. On the same day, Japanese troops marched into Tianjins foreign concessions. Because my father did not wish to collaborate with the Japanese, he took an assumed name and escaped from Tianjin to Shanghai. We joined him there two years later.

In 1945, Japan surrendered and the Second World War was at an end. Chiang Kai-shek was back in charge. His triumph was short-lived because a civil war soon erupted between the Nationalists under Chiang and the Communists under Mao Zedong.

, also known as the original Chinese Cinderella. Isnt it mind-boggling to think that this well-loved fairy tale was already known more than one thousand years ago? My Aunt Baba told me about Ye Xian when I was fourteen years old. You too can read all about Ye Xian in Chapter 22.

, also known as the original Chinese Cinderella. Isnt it mind-boggling to think that this well-loved fairy tale was already known more than one thousand years ago? My Aunt Baba told me about Ye Xian when I was fourteen years old. You too can read all about Ye Xian in Chapter 22. ), whose stories were collected in an encyclopedic book that went through many editions during the last eleven hundred years.

), whose stories were collected in an encyclopedic book that went through many editions during the last eleven hundred years.