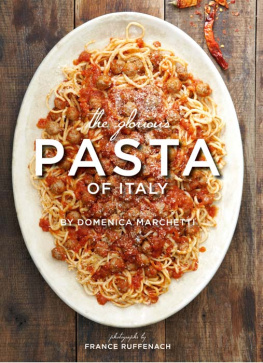

Copyright 2016 by Domenica Marchetti

Photography 2016 by Lauren Volo

All rights reserved.

Food styling by Molly Shuster

Prop styling by Richard Vassilatos

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to trade.permissions@hmhco.com or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

Design by Jan Derevjanik

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Marchetti, Domenica, author. | Volo, Lauren, photographer.

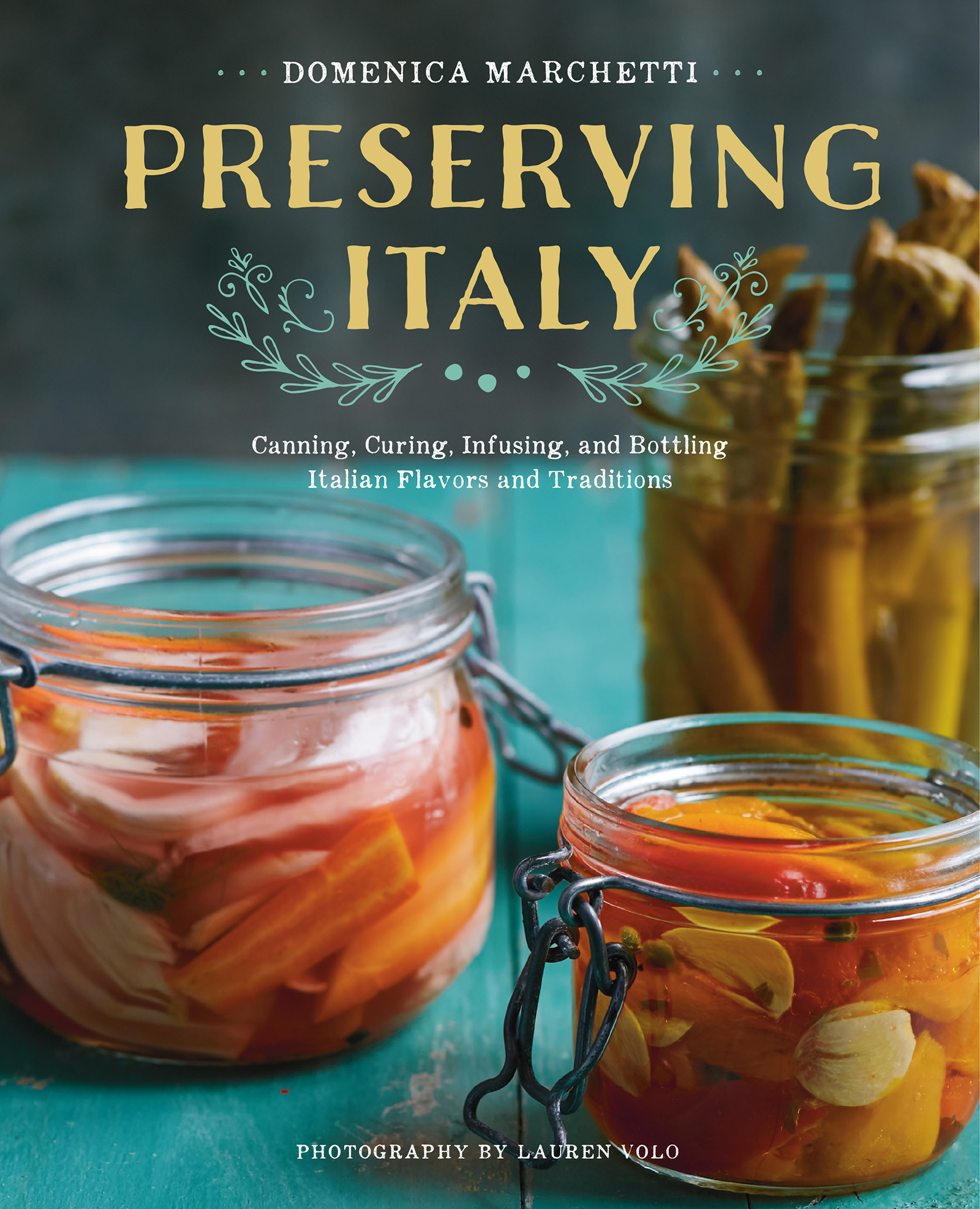

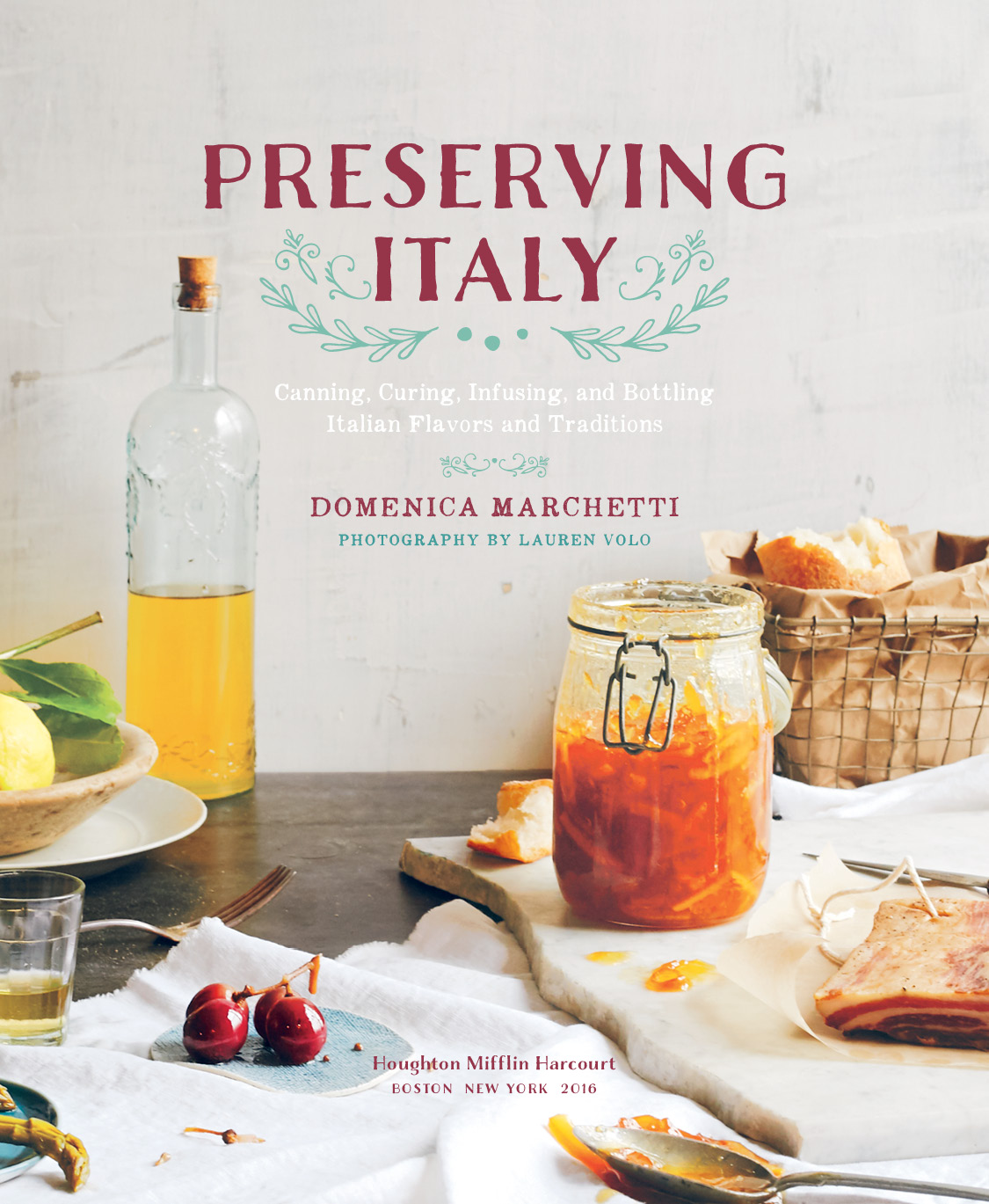

Title: Preserving Italy : canning, curing, infusing, and bottling Italian flavors and traditions / Domenica Marchetti ; photography by Lauren Volo.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015037882| ISBN 9780544611627 (trade paper) | ISBN 9780544612358 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Cooking, Italian. | Canning and preservingItaly. | LCGFT: Cookbooks.

Classification: LCC TX723 .M32655 2016 | DDC 641.5945dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015037882

v1.0616

Contents

Introduction

When my grandmother passed away in 1971, she left behind four grieving daughters and a large jar of her liquor-soaked cherries. The amber glass vessel was filled with tiny sour Amarena cherries that had been dried in the sun and then submerged in a sweet and potent syrup of sugar, alcohol, and spices. The jar was kept in a dark, cool pantry in the family apartment in Rome and the cherries doled out very parsimoniously by my mom and aunts. Even though we were pretty young, my sister and I loved those tiny flavor bombs and their boozy syrup. I cant tell you how many times we feigned mal di pancia (stomach cramps) to get a spoonful. We savored each one until the last was finally consumed four or five years later (yes, they lasted that long).

But when they were gone, they were gone; my grandmother never wrote down the recipe. For years I dreamed of the intense, winey flavor of those tiny cherries and their heavy, spiked syrup. Finally, with help from my momwho recalled her mother making them but had never done it herselfI began working on re-creating the recipe. That quest was the beginning of this book.

I have always enjoyed home preserving. My mother, born and raised in the central-south region of Abruzzo, made a variety of Italian pickles and preserves when I was growing up, from classic giardiniera (mixed vegetable pickle) to sweet, sticky quince jam from fruit that grew on the tree in our New Jersey backyard. I myself was hooked on canning as a hobby from my first attempt at making blueberry jam in my tiny apartment in Michigan, where I worked as a newspaper reporter. Technically the jam was a failureit never setbut the jars pinged, signaling a successful seal, and I ended up with several half-pints of delicious blueberry syrup. For years my specialty was bread-and-butter pickles, which I still put up every August (my brothers-in-law would never forgive me if they didnt get their annual allotment). But over time, my interest naturally gravitated toward the sorts of preserves I had enjoyed growing upmy mothers colorful giardiniera, marinated eggplant packed in oil, vinegary peppers.

The art and craft of preserving is an ancient one, born of necessity and essential to all the worlds cuisines. As with so many culinary endeavors, Italians are masters at it. This is not surprising, given the variety of fruits and vegetables that thrive in the countrys Mediterranean climate and within its many microclimates, and also given the Italian tendencyor compulsiontoward resourcefulness.

Italian cooks put up everything from artichokes to zucchini, in vinegar and in oil; they turn summers berries into jams, and falls apples and quince into russet-hued pastes; they make marmalade from citrus and liqueur out of roots and nuts. In August and September, out come the heavy-duty tomato-milling machines as families get together to can tomatoes every which way. In October, during the vendemmia (grape harvest), the Abruzzesi turn their beloved Montepulciano dAbruzzo grapes not only into wine, but also into mosto cotto, cooked grape must, a caramelly syrup used in cakes and cookies. Then there are the more specialized forms of preservationthe curing of meat; the transformation of milk into cheese; and the metamorphosis of olives from bitter, inedible fruit to tasty antipasto, not to mention that indispensible ingredient, oil.

These days, we tend to think of preserves as extrasa dollop of fig jam on toast, a mound of silky roasted peppers in oil to accompany roast chicken. But in fact, these foods kept families nourished all year long in the days before refrigeration and supermarkets. Whats more, they have played an essential part in defining the regional character of Italian cuisine. In Umbria, cured sausages and salami might be flavored with local truffles; in Calabria they are tinged red from hot chile pepper. Only in Emilia-Romagna and parts of neighboring Lombardy and the Veneto will you find that alluring, ultra-spicy condiment known as mostarda, made from whole pieces of fruit suspended in a nose-tingling hot mustard syrup. In Abruzzo there is scrucchjata, a thick, coarse grape jam made from Montepulciano grapes that is used as a filling for traditional Christmas cookies.

Preserving Italy is a tribute to the many wonderful ways Italians put up food. What began with a search for my grandmothers recipe quickly turned into a full-blown obsession. The more I researched, the more I wanted to know. I wondered about other recipes that were in danger of being lost. After all, life in Italy has changed in the decades since I was a child. Fast-food joints abound and supermarkets are filled with prepared and convenience foods. Fewer people have the time or the inclination to occupy themselves with lengthy, laborious, and sometimes outdated techniques when commercially prepared jars of giardiniera or carciofi sottolio are right at their fingertips on store shelves. But that, Im happy to report, is only part of the story.

Traveling throughout Italy Ive found that, far from disappearing, the art of preserving is thriving, in homes, in restaurants, and in the agriturismi that have opened in the countryside in recent decades. There are also a growing number of artisan producers throughout Italy whose high-quality goods are helping to fuel the movement. In many cases, young people are leading the way. It reminds me of the canning revival that has taken place this side of the Atlantic, with communities of cooks, new and seasoned, coming together to can, preserve, ferment, and brew.

Much of the revival has to do with the Slow Food movement, which began in Italy in 1986 in response to the opening of a McDonalds in Romes Piazza di Spagna. The movement, which became an official organization in 1989, now exists in 150 countries and remains especially active in Italy. Among its various programs is the Slow Food Presidia, which supports producers who work to preserve traditional food-processing methods and foods that are at risk of extinction. One of those producers is Sabato Abagnale, who is dedicated to reviving endangered tomatoes and other vegetables grown around Mt. Vesuvius. Youll meet him within the pages of this book. Youll also meet Paolo Anselmino and Noemi Lora, who switched careers mid-life to start a small business preserving the foods of their native Alta Langa region in Piedmont. Ill introduce you to my friend Francesca Di Nisio, who produces organic olive oil and wine in Abruzzo, and other artisans who are doing wonderful things with food.

Next page

![Better Homes - Better homes and gardens you can can: [a guide to canning, preserving, and pickling]](/uploads/posts/book/188232/thumbs/better-homes-better-homes-and-gardens-you-can.jpg)