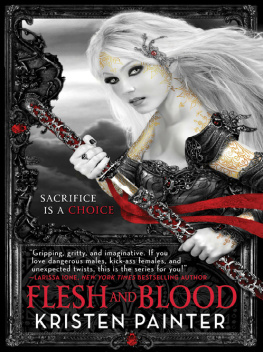

To Heidi

I NTRODUCTION

So who are we, finally? What does our little life mean when measured against the vast ocean swells of life and death that come before us, and roll on through the centuries after were gone? In what ways are we bonded in time to those people who share our surname or our DNA the people we call our family? Are we simply the sum of the individual properties that describe us, or do our actions and choices in response to lifes events form a wider story of kinship and identity?

I think they do. I guess this book is my way of finding out if Im right.

My name is Stephen McGann. Thats what my birth certificate tells me. I was born the fourth son of Joseph McGann and Clare McGann in Liverpool, England, in 1963. Im fifty-four years old and 180 centimetres tall. My passport photograph reveals dark hair and pale skin. I have a drivers licence listing minor traffic convictions. Classified forms residing on government databases record my religious agnosticism and my declared occupation. Im an actor someone whose name might be found in theatrical programme collections or dusty television archives. I married a woman called Heidi Thomas in a church in Liverpool in 1990. Heidi gave birth to our son Dominic in Cambridge in 1996, and my scrawled signature can be seen on his official registration document.

Thats me as data. Facts. Knowledge items, preserved in text or image or on hard drive. Features of an individual, rather than an individuals character. Its an X-ray skeleton essential structure, without the softening subtleties of muscle, vein and flesh. What would someone living 200 years from now be able to learn about me from those facts? Can those items ever coalesce into a recognisable personality the beat of an embodied soul?

Flesh and Blood is a book about people in my family tree some still alive, most of them long dead. Its also a book about me (alive, last time I checked). Flesh and Blood is a family history that begins at a key point in my familys past the mid-nineteenth century and then traces its conflicted progress through the subsequent century and a half to the present day.

Its also, I hope, more than a chronicle more than simply a sequence of events. I dont believe history is ever just a record of something. I think its also a drama. History is about how people responded to recorded events and how they were changed by them; how they grew, shrank, laughed, fought, or fell into despair. History isnt politics or power or the cold clash of steel in ancient quarrels. History is people. Through each human action and response to events we tell a mutating story of our mortal selves. And, through the loves and loyalties that bind us as a family, we tell our own small part in the shifting tale of immortal humanity.

I guess its not difficult for me to reflect on mortality given my current place of residence. You see, I live in a graveyard. Well, not exactly in a graveyard, but surrounded by one. My home is a former chapel, and the grounds include the graves of the Victorian parishioners who helped fund and build it. To get to my front door, you take a small tree-dappled path past crooked gravestones, each bearing faded dedications to the people buried there. Its all very picturesque, but not to everyones taste. The occasional parcel courier takes my signature with startled haste before scarpering back down the path like the fleeing victim in a horror movie. But I love it.

The gravestones are plain, in the nonconformist style. They display simple epitaphs like, Thy will be done or, She is not dead but sleepeth. Theres modesty to them the marking of a life lived but willingly surrendered; a family moved to express love, but not persuaded by the need for excessive detail. The people lying in the ground beneath my couriers fleeing feet seemed to be the recipients of a love that required no hyperbole to make it meaningful. Whats left is the minimum testament to a life: the age of the deceased and the names of their remaining close family. Love as data.

Their modesty made me curious to know more about them. When I perused the original deeds to the chapel, I found that many of the same names on those graves were listed there. These people had funded the chapel between themselves although many were simple rural folk: the deed signed with a single x denoting their illiteracy. They were buried together in its vicinity snuggled in the soil like a single family. These were people whod built a life out of the strength of a faith they shared, and were happy for their lives to be defined by it. They were also content to suffer their harsher moments with quiet restraint.

Mary Jane Bassett. Died in 1933, aged only three years.

Her tiny grave sits close to our door, warmed by the porch light. A childs death is the oldest of those answerless questions an ancient outrage longing for explanation. I wondered if little Marys life was larger than the miniature plot that now swaddled her, if the unvisited silence of her grave had once been attended by the voices and hands of those who loved her.

Then, one day, a middle-aged lady called by our house. The previous owners had told us she might. Her mother was buried in our garden, and she had attended the chapel as a young girl. She asked if it was possible to continue her occasional visits to tend her mothers grave. We were very pleased to oblige. When the lady saw little Marys plot, a memory returned. She recalled her mother speaking of this girl, and of her moving funeral. She said that the other children of the chapel had carried Marys tiny coffin on their little shoulders to its final resting place.

I loved that. A single beautiful scene. History as drama. A child so loved and cherished she was carried to her grave by her fellow innocents. Marys face had suddenly been summoned into the porch light of a narrated memory. She breathed again. She lived.

Who was Mary, finally? She was a story woven by those who still carried her memory through time. By hearing this story, and now relating it to you, Ive taken my place as one of Marys bearers. And so she lives on, carried by us all in this tiny story fragment. The lesson of little Mary is that we are only recorded data in the absence of a better insight. We are always more. Always more human. Always more meaningful than facts. Data is just the starting place. The beginning of the journey, not its end. We are a story, not a stone.

And so it is with my family in this book. Flesh and Blood is a book about relatives to whom things happened, but also not really a book about those things. Its more about the way those people responded to events that afflicted them, and how those responses came to define the people they were, and the lives of the family that succeeded them. To tell this story, Ive combined three separate lifelong preoccupations. First is my interest in genealogy the study of my family history through the public records. The second is my life spent as an actor portraying the mechanics of human motivation in drama. The third is my academic interest in the relationship between medical health and the complex society that it helps to sustain. This book is therefore a single familys story refracted into three primary colours of experience: health, family history and the drama of human testimony.

I first started tracing my family tree when I was seventeen a gauche teenager on the cusp of an adulthood I didnt yet understand. My search for a wider context to my life made me curious about the people whod come before me the McGann family, the ones whod given me my surname. Who were they? What did they do with their lives, and how did that end up with me? I knew nothing about them, and my father knew very little more than I did. His dad had died when he was just five years old, and the children who remained were left with only second-hand scraps of stories from their mother. McGann was an Irish name, and Liverpool, I knew, was a famous embarkation point for Irish emigration to the United States in the nineteenth century. I assumed they were Irish, but didnt know for sure. So one day I plucked up courage and ventured into my local records office in Liverpool to see if I could find out. I began, piece by piece, to build up a data skeleton of my ancestry from records held in our public archives. It was the beginning of a genealogical journey that has taken me my entire life, and is still a work in progress.