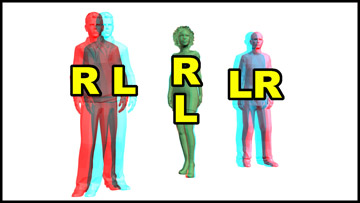

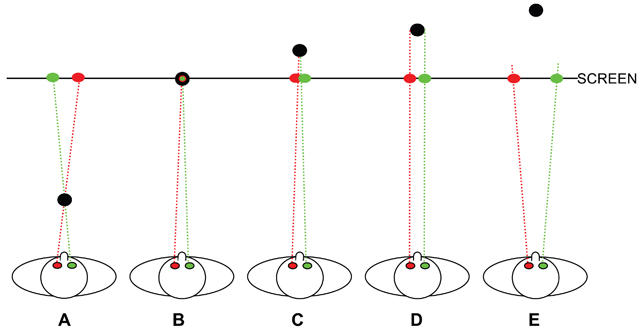

Viewers Left and Right Eye Orientation to a Stereoscopic Image Pair

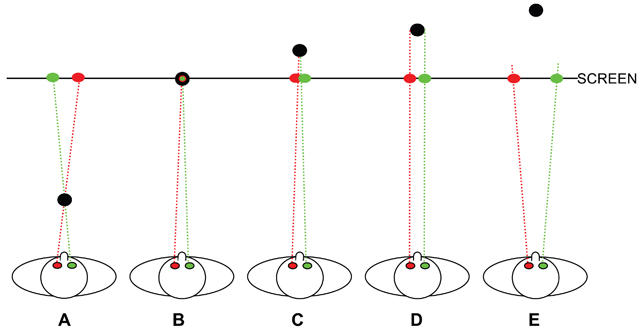

The position of an object in front of or behind the screen is determined by how the viewers eyes see the image pair.

Your eyes receive an objects image pair differently depending on where the object should appear in depth.

Objects appearing on the screen plane (green actor) dont seem to have an image pair but they do. The pair of images is superimposed over each other. Objects that appear on the screen plane have zero parallax separation ( zero parallax setting or ZPS ).

When an object appears behind the screen plane (blue actor) the image pair is correctly oriented to your eyes. Your left eye looks to the left image and your right eye looks to the right image. Objects that appear behind the screen plane have positive parallax .

When an object appears in front of the screen plane (red actor) the image pair is flipped. The left eye image is offset to the right and the right eye image is offset to the left. Objects that appear in front of the screen plane have negative parallax .

- Objects appearing in front of the screen require the viewers eyes to converge and cross . We converge and cross our eyes when we look at close objects in real life, too. You are converging when you read this book. The difference is that in a 3D movie you are converging in front of the screen even though the image of the object is on the screen surface. Notice that the image pair is flipped. The viewers left eye sees the screen right image and the viewers right eye sees the screen left image.

- Objects that appear on the screen plane require the viewer to converge or cross at a point on the screen surface.

- Objects that appear behind the screen require the viewer to converge at a point beyond the screen. The image pair is no longer flipped. Now, the viewers right eye sees the right image and the viewers left eye sees the left image.

- Objects appearing at infinity require the viewers gaze to remain parallel . This is similar to what the eyes do in real life when we look at distant objects.

- Objects with a parallax separation greater than 2.5 inches of measured screen distance will appear farther away than infinity. This causes the eyes to diverge .

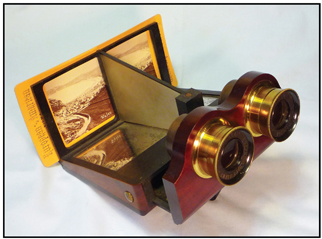

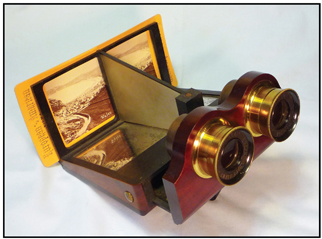

Photo courtesy of Pinsky/Starkman Collection

Stereoscopic 3D photography has been around since about 1840. Originally, it referred to the optical illusion of depth in still photographs. Early stereoscopes, like the one pictured above from 1859, displayed two nearly identical photographs, one seen only by the left eye and one seen only by the right eye. The observer would look through the two lenses and their brain would combine the two photos into a single image that appeared to have three-dimensional depth.

The first stereoscopic feature length film, The Power of Love , was shown in 1922. But stereoscopic movies remained nothing more than a novelty. In the 1950s, stereoscopic 3D features like House of Wax and Bwana Devil created a 3D movie fad that only lasted about three years. Another revival attempt was made in the early 1980s but 3D remained on the fringes of major film production.

The digital age has made reliable stereoscopic 3D photography and display possible on large theatre screens, consumer televisions, and computers. This technical revolution has led to a renaissance in stereoscopic 3D production.

The term 3D was originally coined in the early 1950s. Audiences learned that 3D movies meant putting on special glasses and watching a stereoscopic movie on the big screen.

In the late 1970s, Hollywood began using computers in feature film production. CGI (Computer Generated Imaging) or CG (Computer Graphics) were used to create visual effects and as an alternative to hand-drawn animation. These computer-based images were, unfortunately, called 3D because they were created in a computers virtual three-dimensional environment. Suddenly, the term 3D had two completely different meanings.

Today, the term 3D still refers to computer-generated visual effects, CG animation, and stereoscopic pictures. In this book, 3D refers only to stereoscopic 3D.

Chapter Three

The Six Visual Sins

Historically, 3D movies have been associated with audience eyestrain and headaches due to technical issues and poor planning. The real problem was not eyestrain; it was brain strain. A viewers eyes can only send images to the brain with a note attached: Here are two pictures, figure it out. If the brain cant figure it out it will unnaturally realign the eyes or become confused by the two conflicting images sent from the eyes. Eventually, the brain goes into strain mode and the audience gets headaches, eyestrain, and occasionally nausea.

In 3D, there are specific technical issues that can cause audience brain strain. Well call these problems the Six Visual Sins. They are:

- Divergence

- Coupling and Decoupling

- Geometry Errors

- Ghosting

- Window Violations

- Point-of-Attention Jumps

There are three main factors that contribute to the negative effects the Six Visual Sins can have on the audience:

1. Where is the audience looking? The Six Visual Sins cant cause problems if the audience doesnt look at them. Every shot has a subject and a lot of non-subjects. The audience spends most of its time, or all of its time, looking at the subject. The subject is the actors face, the speeding car, the alien creature, the adorable dog etc. If the Six Visual Sins have impacted the subject, the audience sees the problem and gets brain strain.

But most of a scene is not the subject. Peripheral objects, backgrounds, unimportant characters, crowds etc. are all non-subjects that the audience acknowledges but tends to ignore in favor of the subject. Non-subjects can tolerate most of the Six Visual Sins because the audience is looking elsewhere.

2. Whats the screen size? The problems caused by the Six Visual Sins can occur on any size screen, but the problems become more severe as the screen gets larger.

3. How long is the screen time? Time is critical. The longer the audience looks at the Six Visual Sins the greater the risk of brain strain. All of the Sins have degrees of strength and may cause instantaneous discomfort or take more time to have a negative effect on the audience. Brief 3D movies like those shown in theme park thrill-rides can get away with using the Six Visual Sins in ways that would be unsustainable in a feature-length movie. An audience can even tolerate the Six Visual Sins in a long movie if the Sins appearance is brief.

Fortunately, all of the Six Visual Sins can be avoided or controlled to create a comfortable 3D viewing situation. The following discussion of the Six Visual Sins assumes the 3D is being presented on a 40-foot theatre screen.

A stereoscopic 3D movie may require the audiences eyes to diverge . This can be a serious viewing problem and can cause brain strain.