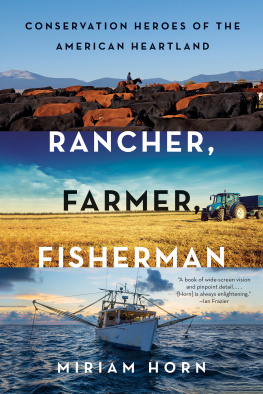

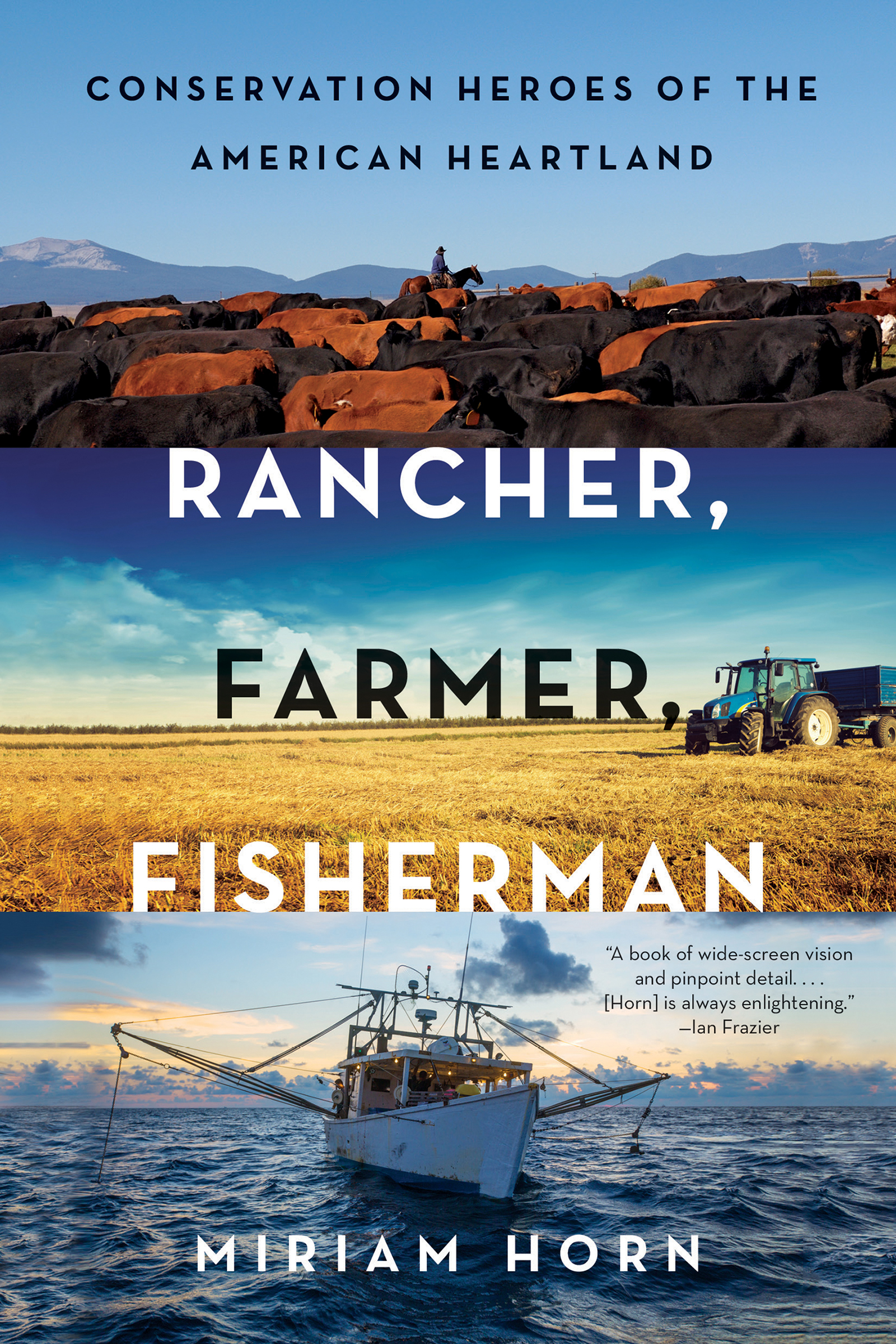

RANCHER,

FARMER,

FISHERMAN

CONSERVATION HEROES OF

THE AMERICAN HEARTLAND

MIRIAM HORN

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York London

Copyright 2016 by Miriam Horn

All rights reserved

First published as a Norton paperback 2017

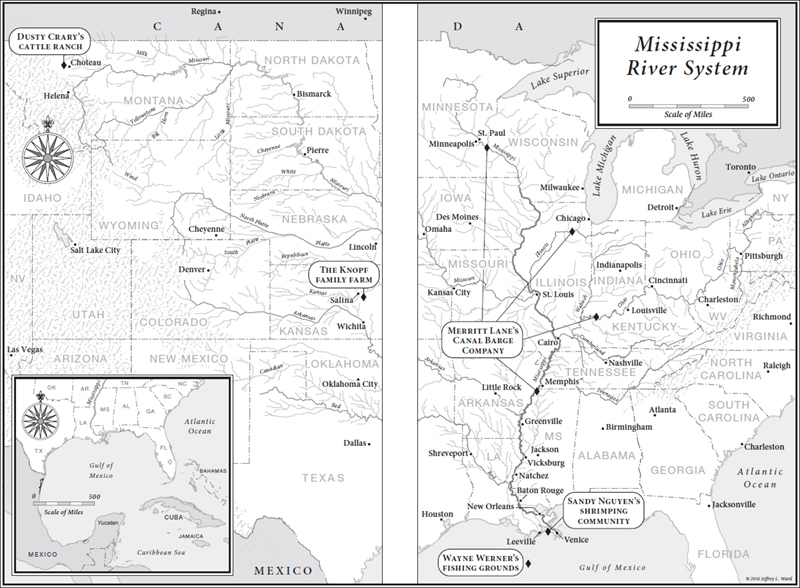

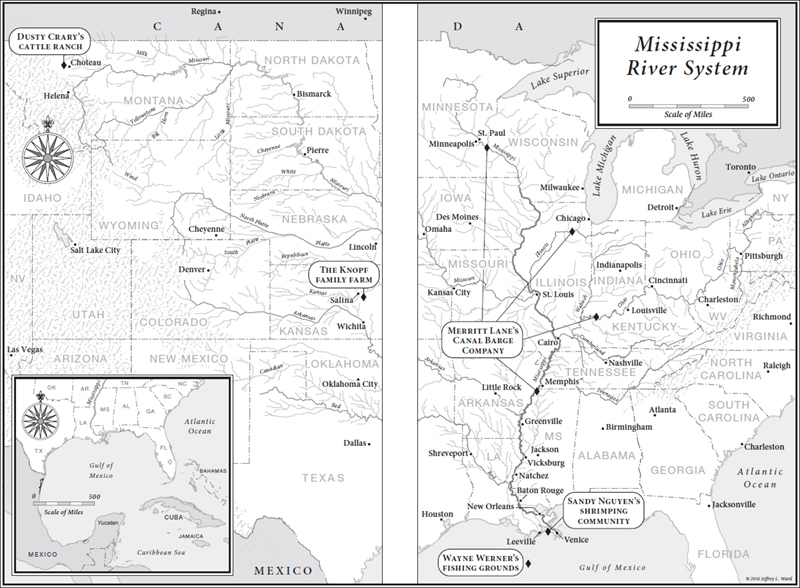

Mississippi River System map on pp. xxi Jeffrey L. Ward; photograph on p. xx courtesy of Discovery Channel from the film Rancher, Farmer, Fisherman / Beth Alala; photographs on pp. 80 and 208 courtesy of Discovery Channel from the film Rancher, Farmer, Fisherman / DP Buddy Squires; Louisiana land loss map on p. 171 courtesy of the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority; photograph on p. 254 Otis Dobson.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Ellen Cipriano Design

Production manager: Julia Druskin

Jacket design by Eric Fuentecilla

Jacket photographs: (top) Cgbaldauf / Getty Images; (middle) Avalon Studio / Getty Images ; (bottom) JohN Rae

ISBN 978-0-393-24734-3

ISBN 978-0-393-24735-0 (e-book)

ISBN 978-0-393-35487-4 (pbk)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

for Francesca

RANCHER,

FARMER,

FISHERMAN

The land belongs to the future... thats the way it seems to me... I might as well try to will the sunset over there to my brothers children. We come and go, but the land is always here. And the people who love it and understand it are the people who own itfor a little while.

WILLA CATHER, O PIONEERS!

WITH HIS envoys in Paris negotiating to purchase Louisiana, Thomas Jefferson implored his friend and fellow farmer James Monroe to join them, to secure our rights and interest in the Mississippi River and surrounding territories. On the event of this mission, the president wrote in January 1803, depends the future destinies of this Republic.

Jeffersons imminent concern was possible war with France, but his words would prove prophetic across centuries. The Mississippi River watershedan immense funnel spun of 7,000 tributaries reaching from the Rockies to the Appalachians and draining 40 percent of the continental United Statesis central to the American story. The third largest in the world (behind only the Amazon and the Congo), this basin holds most of the nations natural wealth and produces most of its minerals and food: metals and coal from its mountains, meat from its northern grasslands, grains and beans from its central plains, fish and black oil from its delta. The connectivity provided by its thousands of miles of waterwayslinking the heartland to the rest of the nation and the worldhas been critical to Americas rise and reign as a global economic power. The nations politics, too, have been crucially shaped in these middle reaches, for two hundred years the place to sort out such fundamental questions of democracy as the proper balance between federal and local authority. Most important have been the values born here: on this iconic terrainthese mountain majesties, fruited plains, shining seasexplorers and cowboys, pioneers and riverboat captains, forged the American identity. It is not by chance that the Mississippi provided the setting for two of Americas founding journeys: Lewis and Clarks up from St. Louis to the Missouri headwaters and across the whole of the Louisiana Purchase Jefferson sent them to explore, and Huck Finns down the river, to freedom and an understanding of the common human purpose.

America depends on these grand working landscapes, and they in turn depend on a small number of people: the families who live by harvesting their bounty. Farmers and ranchers make up just 1 percent of the U.S. population but manage two-thirds of the nations land; agriculture has greater impacts on water, land and terrestrial biodiversity than any other human enterprise. Thats true everywhere, making this region a model for the world. Half of Earths ice-free land is in pasture or farms. Crops now cover an area the size of South America and livestock graze an expanse as big as Africa; together they use 70 percent of all fresh water. Fishermen have an equally enormous impact, harvesting 90 million metric tons of fish annually equivalent, as author Paul Greenberg calculates, to pulling the human weight of China out of the sea every year.

As these productive landscapes grow increasingly precariousovergrazed, overtilled, overfished; threatened by invasive species, development, ill-conceived feats of engineering, and extreme weatherit is the families who run the tractors and barges and fishing boats who are stepping up to save them. Theirs are the most consequential efforts to restore Americas grasslands, wildlife, soils, rivers, wetlands and fisheriesthe vast, rich bounty that shaped our national character and sustains our way of life.

In the still half-wild frontier of the northern Rockies, near the headwaters of the Missouri 4,000 miles upstream from the Mississippis mouth, Montana cowboy Dusty Crary has gathered an improbable band of longtime enemiescattlemen, fishermen, federal land managers, outfitters, hikers, hunters, environmentaliststo protect the epic ranches and untamed wilderness and elk and grizzlies and trout they all love. On the Kansas prairie, Justin Knopf is using industrial-scale farming to restore depleted soils cultivated by his family since homestead days. On the Mississippi itself and its sultry delta, Canal Barge CEO Merritt Lanescion of an old aristocratic Southern familyhas joined an unprecedentedly ambitious effort to reestablish the rivers natural land-building functions, to protect his mariners and New Orleans. On the Louisiana bayou, Sandy Nguyen is building alliances to rescue the estuaries that harbor the shrimp and oysters and crabs her community relies on. And in the deep blue waters of the Gulf of Mexico, beyond the rivers mouth, commercial fisherman Wayne Werner is tangling with fisheries regulators to bring back red snapper and keep his and his buddies small businesses afloat. The challenges they face are nearly as daunting as those met by their forebears when they settled the frontier, founded companies in the depths of the Depression, or fled war and Communism in tiny fishing boats adrift on vast seas. But like those ancestors, they draw on deep reservoirs of courage, ingenuity, optimism and resolve.

All are conservationists because their livelihoods and communities will live or die with these ecosystems, but also because they love these land- and river- and seascapes where natures elemental forces remain vivid in their beauty and danger; where lives of self-creation, self-reliance and liberty remain possible; where the ideas of home and homeland remain strong. All bear a sense of moral responsibility to both the future and the past, a determination to pass on to their children and grandchildren a heritage often generations deep: the family memories imprinted on this land, the seasonal rhythms and traditions built around the bounty they reap. Many acknowledge something sacred herelarger than human understanding or will, a gift to be tended and revered.

Next page