Contents

Guide

Page List

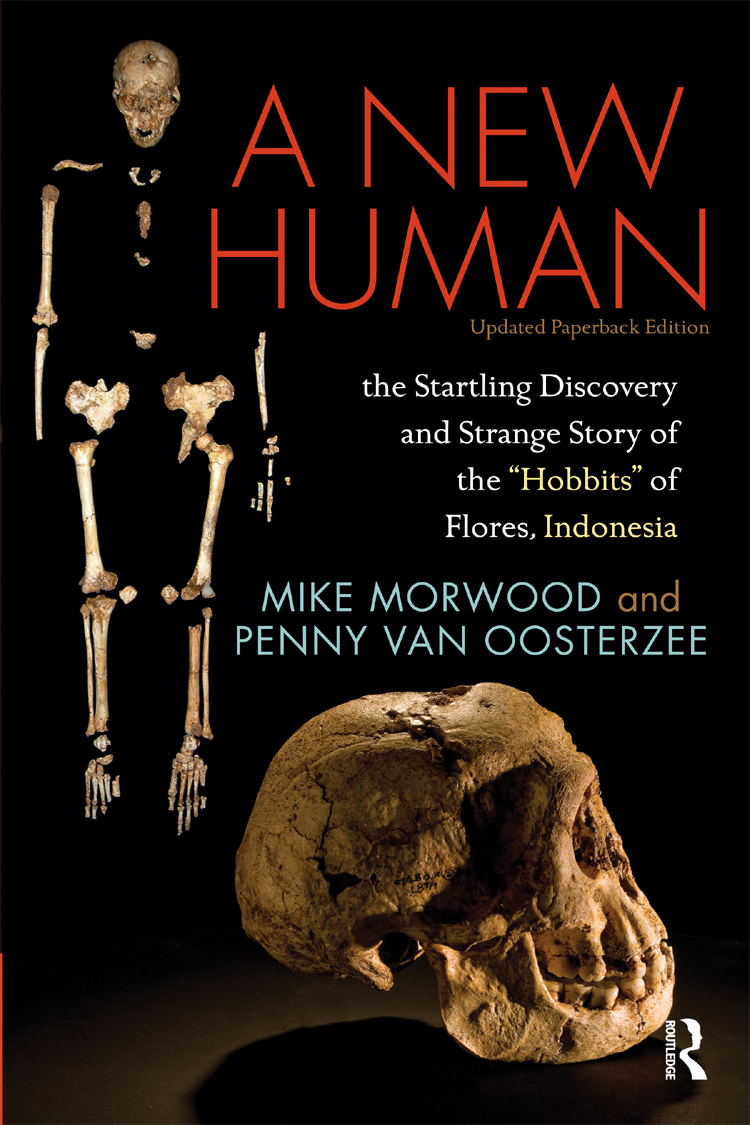

A NEW HUMAN

A NEW HUMAN

The Startling Discovery and Strange Story of the Hobbits of Flores, Indonesia

UPDATED PAPERBACK EDITION

Mike Morwood

and

Penny van Oosterzee

First published 2007 by Left Coast Press, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint o f the Taylor & Franc is Group, an info rma business

Copyright 2007 by Mike Morwood and Penny van Oostersee

New paperback edition material copyright 2009 by Mike Morwood and Penny van Oostersee

Originally published in the United State in hardcover by Smithsonian Books/ HarperCollins in 2007 under ISBN 978-0-06-089908-5

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data:

Morwood, M. J. (Mike J.) A new human: the startling discovery and strange story of the hobbits of Flores, Indonesia/ Mike Morwood and Penny van Oosterzeep. cm.

ISBN 978-1-5987-4414-9

ISBN10: 978-1-3154-3565-7 1.Fossil hominidsIndonesiaFlores Island. 2. Fossil hominids AustraliaKimberley (W.A.). 3. PygmiesIndonesiaFlores Island. 4. PygmiesAustraliaKimberley (W.A.). 5. Human beingsMigrations. 6. Excavations (Archaeology)IndonesiaFlores Island. 7. Excavation (Archaeology)AustraliaKimberley (W.A.). 8. Human remains (Archaeology)IndonesiaFlores Island. 9. Human remains (Archaeology)AustraliaKimberley (W.A.). 10. Flores IslandAntiquities. 11. Kimberley (W.A.)Antiquities. I. Van Oosterzee, Penny. II. Title.

GN730.32.I5M67 2007994.01dc22 2006052267

Designed by Stephanie Huntwork

ISBN13: 978-1-59874-414-9 paperback

CONTENTS

Prologue

J ack tossed a match into the clump of spinifex, which exploded into flame. A few more matches in a few more clumps and there was a wall of fire up to five meters high and spreading fast. The accompanying roar made it difficult to hear anything else, and the acrid smoke made it difficult to see, so we hastily retreated to our boat beached among the mangroves. As we motored to our camp across the inlet, I looked back to see a gigantic pall of smoke reaching hundreds of meters into the sky with Jack at the back of the boat silhouetted against the inferno. Jack Karadada, a Wunambal Aboriginal elder and one of the traditional owners for this remote stretch of the Kimberley coastline in the northwest corner of Australia, had taken the opportunity of our visit to clean up his country, which by traditional custom should be burned regularly. The fire would burn for weeks across this vast, rugged, empty landscape.

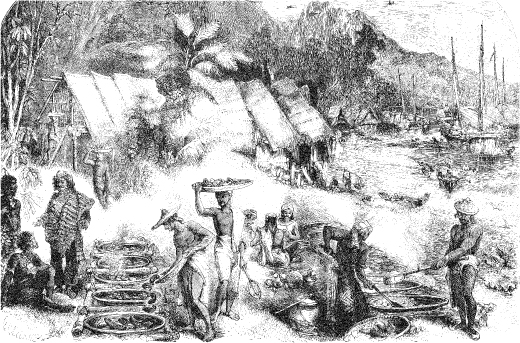

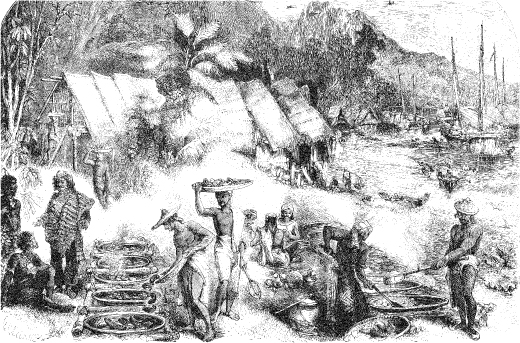

Until Jacks cleaning up the country brought our work to a halt, my colleague Doug Hobbs and I had been recording a major Indonesian site for processing of trepang, or sea cucumbersa group of animals related to sea stars and sea urchins that the Chinese value as a delicacy and an aphrodisiac. At this site, we had found evidence for processing on an industrial scale. There were 18 lines of stone fireplaces that had supported cauldrons for boiling trepang, while scattered on the ground all around were pieces of pottery from Java, Sulawesi and China, left by Macassan, Buginese and Bajau fishermen.

There are hundreds of such processing sites around the coasts of the Kimberley and Arnhem Landknown to Indonesian fishermen as Marege and Kaju Djawa, respectively. Large-scale Indonesian visits to northern Australia to collect trepang began in historical times, and the actual date for the commencement of the industry is known. Meticulously kept records of the Dutch East Indies Company show that from 1700 CE, the fishermen came sailing on the northwest monsoon winds to northern Australia for trepang, which they collected in shallow coastal waters, then brought ashore to be gutted, boiled and smoked in prefabricated smokehouses. The fishermen stayed until the winds swung around, when they sailed back on the southeast trades, laden with trepang for the Chinese market.

An Indonesian trepang-processing site drawn around 18431844. Remains of such Asian sites are found along the coast of the Kimberly, Arnhem Land and the Gulf of Carpentaria. (THE QUEEN, FEBRUARY 1862)

That was not the first time Asians had come to Australia. Archaeological evidence suggests much earlier visits by seafarers, before the trepang trade and long before historical records were kept. The appearance of the dog in Australia about 4,000 years ago, for instance, must have resulted from Asian contactsimilarly the appearance of the pig in New Guinea about the same time. Going back further still, the initial colonization of Australia and New Guinea by modern humans at least 50,000 years ago is another indisputable example of outside contact: the fossil record makes it clear that humans did not originate there.

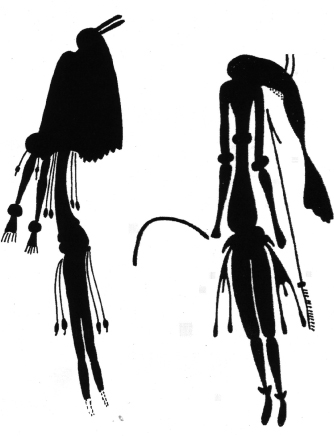

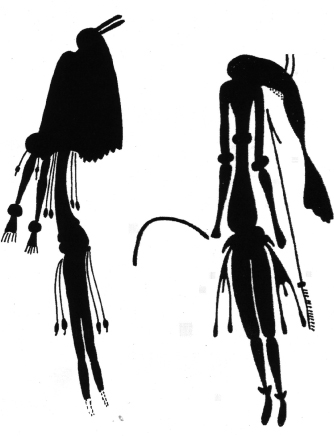

The complex rock art styles and languages found in northwest Australia suggest cultural exchange and population movement over a long time between Asia, New Guinea and Australia. The exquisite Bradshaw and stylistically related Dynamic Figure rock paintings, for instance, which are more than 20,000 years old, have a degree of anatomical detail, composition and movement seldom matched in any other Australian Aboriginal art tradition, but are very similar to rock paintings found in Borneo that are more than 10,000 years old. Bradshaws, Dynamics and other Complex Figurative art styles, such as Wandjina and X-ray paintings, are only found in the Kimberley, Arnhem Land and adjacent regions of northwest Australia.

The sophistication and complexity of the art is matched by the diversity of languages: there are 18 Australian Aboriginal language families, 17 of which are found only in the northwest. The hundreds of languages found throughout the rest of the continent all belong to just one language family, Pama-Nyungan.

For 20 years, as a lecturer at the University of New England (UNE) in Armidale, New South Wales, I had been doing research on Australian Aboriginal archaeology, progressively working farther north, then west, with regional projects in Southeast Queensland, the Central Queensland Highlands, the North Queensland Highlands, Cape York Peninsula, and then the Kimberleythe latter being one of the likely beachheads for the first people to reach these shores.

Bradshaw rock paintings in the Kimberly region of northwest Australia are more than 20,000 years old. Only rock art styles in the Kimberly, Arnhem Land and adjacent regions of the northwest have this degree of figurative detail.

A NEW HUMAN

A NEW HUMAN