THE EDITORS AND AUTHORS thank the staff and administration of the American Academy in Rome, where our original discussions regarding this project took place. Roberto Einaudi, who assisted Pier Luigi Nervi with the translation and presentation of the original Norton Lectures, has provided not only an authoritative history of the events themselves but has also graciously proofread the original English texts of Aesthetics and Technology in Building, and has made a handful of editorial changes in the interests of both fidelity to Nervi's intent and overall clarity. We would also like to thank John Doherty for his translation of Jo Abram's essay.

This volume constitutes the critical re-publication of the original edition of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures held by Pier Luigi Nervi, issued by Harvard University Press in 1965. We are grateful to them for giving the rights to the original texts to the Pier Luigi Nervi Project Association and to Eric Jooris for assisting in the process.

Finally, we are grateful to Iowa State University's Subvention Publication Grant program, which provided funds crucial to the production of this book, and to the staff of the University of Illinois Press, who have been diligent in bringing Nervi's timeless words to a new generation.

AFTERWORD

Pier Luigi Nervi

An Aesthetic of Thinking

JOSEPH ABRAM

MAKING A POEM IS A POEM, wrote Paul Valry. Solving a problem is an ordered game in which chance and uncertainty are defined pieces. into actuality.

It is from this theoretical perspective on form, as envisaged by Valry, that I propose to analyze Pier Luigi Nervi's heuristic itinerary. One of the major obstacles to an examination of his work is its self-evidencethe instantaneous The power of Nervi's work, in my view, lies in his twofold mastery of material and nonmaterial constraintsthose forces that are measurable and those that are notand his ability to bring them together in a significant totality that, given the chaotic history of the materials he utilized, seems almost unreal. In the early twentieth century, reinforced concrete, on account of both its novelty and its position in the continuum of contemporary constructive methods, posed a new problem for engineers and architects, and one that called into question the foundations of construction techniques. To this problem, Nervi provided a solution that was both individual and universal.

An Enigmatic Material

Talking about the early days of reinforced concrete, the Swiss engineer Robert Maillart recalled the almost insurmountable impediments that stood in its way. Hennebique's invention was ridiculed, while his primitive methods of calculation gave rise to justified criticisms that caused the entire system to be rejected. But nothing could prevent the development of this mode of construction, which was both practical and economical.

Franois Hennebique turned it into a universal mode of construction, and, after producing the first reinforced concrete slab using round-section rods in 1880, he made it his specialty. Within a decade, the system he patented in 1892, and the company he founded, had spawned a global network of some fifty concessionaires with a total of more than ten thousand employees.

And indeed the brothers Auguste and Gustave Perret were being quite audacious when, in 1903, they used it for the delicate frame of a building.

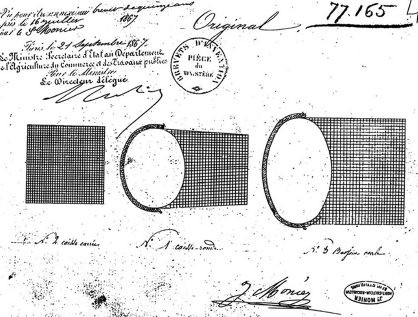

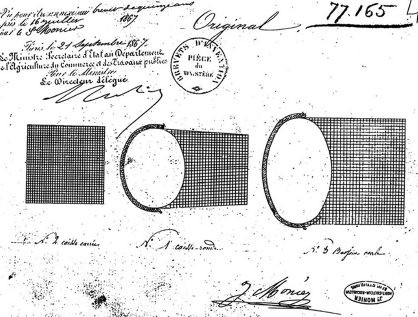

FIG. 1. Joseph Monier, patent for a system of box-basins of iron and cement for horticulture, 1867.

With the garage in Rue de Ponthieu, the Perrets gave architectural expression to Hennebique's constructive innovations,

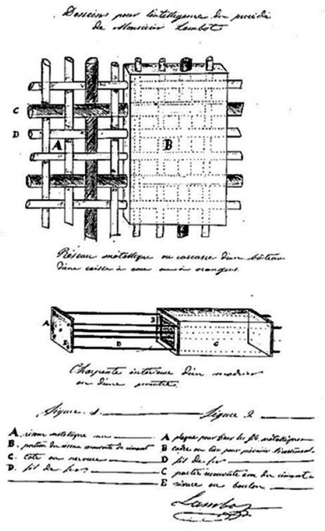

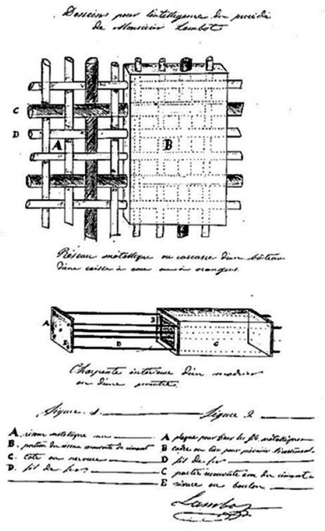

FIG. 2. Joseph Lambot, patent for a system of construction in ciment arm, 1855.

FIG. 3. Joseph Lambot, prototype for a boat in ciment arm displayed at the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1855.

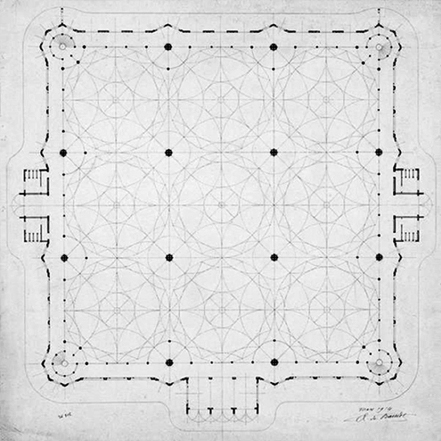

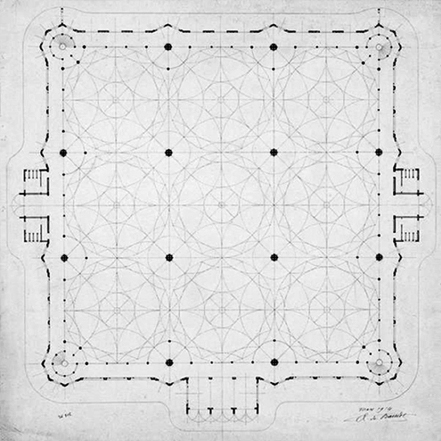

FIG. 4. Anatole de Baudot, project for a large space, plan, 1914. Anatole de Baudot, L'architecture, le pass, le prsent.

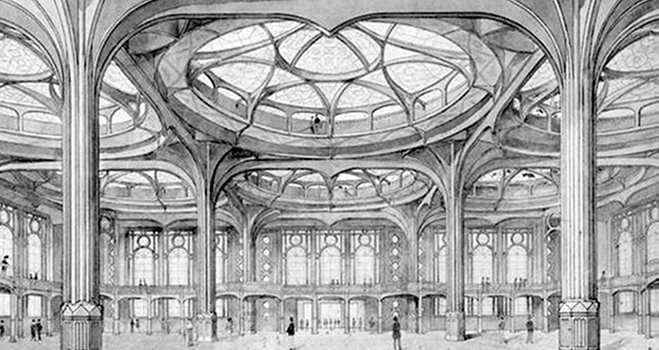

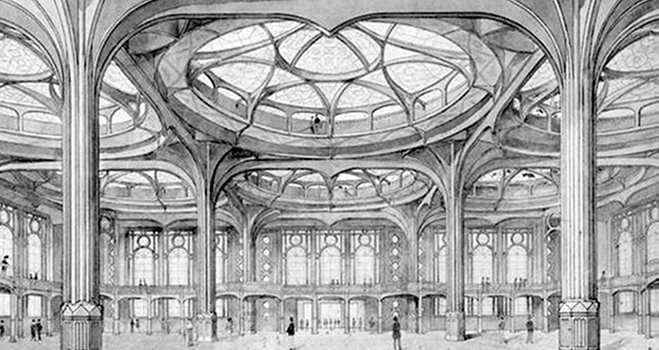

FIG. 5. Anatole de Baudot, project for a large space, perspective, 1914. Anatole de Baudot, L'architecture, le pass, le prsent.

FIG. 6. Anatole de Baudot, project for a large hall, perspective, 1914. Anatole de Baudot, L'architecture, le pass, le prsent.

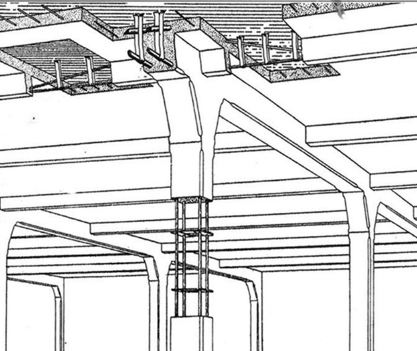

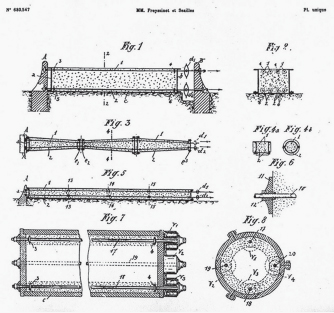

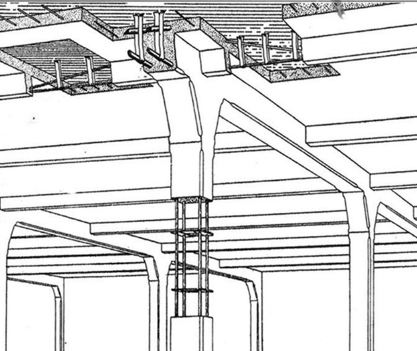

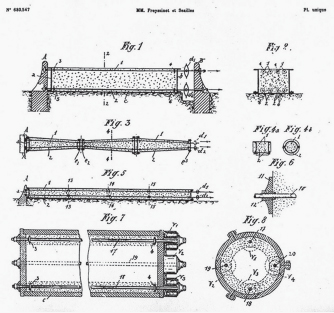

FIG. 7. Franois Hennebique, method of construction en bton arm, 1892.

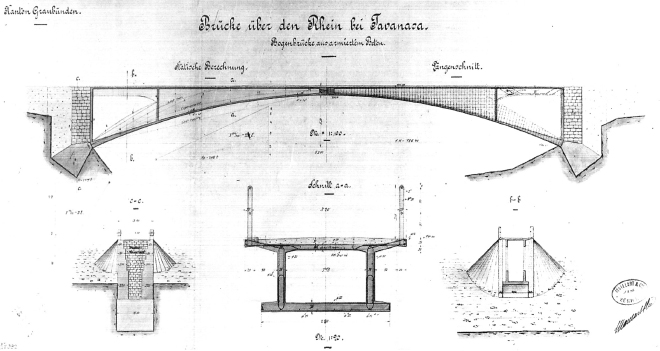

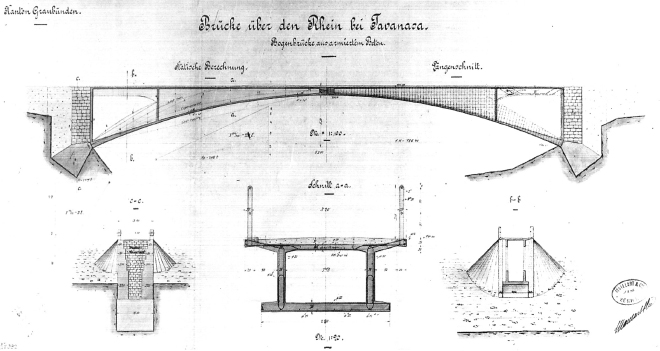

FIG. 8. Robert Maillart, project for the Tavanasa Bridge, 1905.

Stresses and Distortions

In 1910, when Nervi enrolled at the prestigious Scuola di Applicazione per Ingegneri in Bologna, reinforced concrete was taking over the world. There were also virulent debates about its composite character and the ability of mathematical models to describe its behavior. In Bologna, Nervi studied civil engineering. But the curriculum was broad-based, and it included basic science (mathematics, physics, and natural sciences), applied engineering, and courses in artistic disciplines, including architecture at the Accademia di Belle Arti. Nervi was profoundly marked by this experience, which combined technical skills with aesthetics. Two professors played a decisive role in his ideas about reinforced concrete. Silvio Canevazzi cautioned him to be wary of theoretical dogmas disconnected from experimental verification. And then there was Attilio Muggia, who was both a teacher and a practitioner, and who, in 1895, had acquired a license to use Hennebique's system in Italy.

FIG. 9. Eugne Freyssinet, Pont de Boutiron (190712). (Photo by Joseph Abram)

FIG. 10. Eugne Freyssinet and Jean Sailles, original patent for prestressed concrete, 1928.

FIG. 11. Eugne Freyssinet, Pont du Veurdre (190711). (Photo by DR).

Nervi graduated in 1913, and he began his career in Muggia's firm, Societ Anonima per le Construzioni Cementizie (SACC), in Bologna. At this point, reinforced concrete was still far from having won general acceptance. During a debate on Hennebique's Ponte del Risorgimento, in Rome, Canevazzi informed his students that he had received letters from German theoreticians, claiming that, though already in operation, the bridge would not hold up. Flying in the face of reality, none of these researchers imagined that the theoretical predictions could be inexact. This is the kind of practical expertise that Nervi built up during the 1920s, and it heralded the structural innovations he implemented, for example, in the Stadio Comunale of Florence (193032) or the hangars in Orvieto (193538).