Navy Pier: A Chicago Landmark

Navy Pier

A Chicago Landmark

Douglas Bukowski

Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority 1996

Published by

Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority

2301 S. Prairie Avenue

Chicago, Illinois 60616

All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, copied, or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher.

All photographs without specific credit lines are used courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society.

Cover photo by Vito Palmisano

Distributed by

Ivan R. Dee, Inc.

Publisher

1332 North Halsted Street

Chicago, Illinois 60622-2637

Fax: 312-787-6269

Phone: 312-787-6262

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bukowski, Douglas, 1952

Navy Pier : a Chicago landmark / Douglas Bukowski.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-1-56663-115-0 ISBN 1-56663-115-7 (paperback) 1. Navy Pier (Chicago, Ill.)History. 2. Navy Pier (Chicago, Ill.)HistoryPictorial works. 3. Chicago (Ill.)Buildings, structures, etc. 4. Chicago (Ill.)Buildings, structures, etc.Pictorial works. I. Title.

F548.63.N38B85 1996

725.80420977311dc20

96-7710

CIP

Contents

Preface

City landmarks are precious things. All too often, events conspire to take from us places filled with memory and history: the ballpark of Appling and Veeck, the movie house where we watched enviously as Charlton Heston drove his chariot, the amusement park that promised it would make us laugh our troubles away. When these places vanish, we lose part of ourselves; we also lose a connection to those who came before us and to those who will follow. These are the times when the price of progress becomes too expensive.

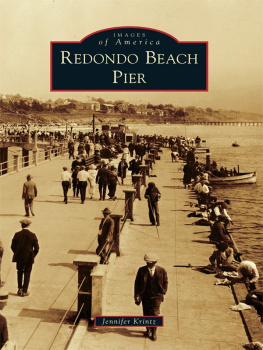

Since its opening in 1916, Navy Pier has been every bit a landmark. As a youngster in the 1920s, my father traveled to the pier so he could board a steamer, the S.S. Carolina, that would take him to Boy Scout camp across Lake Michigan. In the 1950s, I attended trade fairs at the pier. I do not recall meeting Queen Elizabeth or Prince Philip, but I distinctly remember the toy ambulance my mother bought for me; it was a Chevrolet. I also remember the ships sent by the navy, as far and many as my small eyes could see.

My sister was one of the 100,000 students who would attend the University of Illinois at Navy Pier. She took me with her one evening, and I was able to see what she did every school day. The hallways were incredibly long (and, I learned later, the time between classes far too short). But she seemed to enjoy the experience.

Together with many other Chicagoans, I rediscovered the pier during the Bicentennial in 1976. I came to see the tall ship Christian Radich and stayed for the scenery. It was incomprehensible to me that the pier should have fallen into disuse. Like city architect Jerome Butler, who did so much then and more recently to restore the pier, I realized that a grand ballroom on the lakefront is not a resource to be wasted.

I now take my family to the rebuilt Navy Pier. My daughter can see where her grandfather left for camp and her aunt scurried to class; all the family memories are there as the pier readies itself to create more.

This book offers the public story of Navy Pierits roots in the Chicago Plan and the citys attempt to become a world port; its use by Big Bill Thompson for his Pageants of Progress; the first Golden Age, when Chicagoans came to stroll and eat and play; and the piers role as a school both during and after World War II. It also tells the story of the piers decline as a harbor facility and near demise, its proposed use as the foundation for a space needle, and its dominance of Chicago politics as a development issue. ChicagoFest also receives its due, assuming that words can capture the excitement and crowds of those summer celebrations. Somehow, the pier survived it all.

And now, as Navy Pier closes in on its one hundredth birthday, it will continue to greet visitors into the next century. This is all any landmark could want.

Doug Bukowski

Chicagos first permanent resident was the Haitian emigre Jean Baptiste Point du Sable (insert). Like those who followed him, du Sable understood that water transportation would be the key to the regions development.

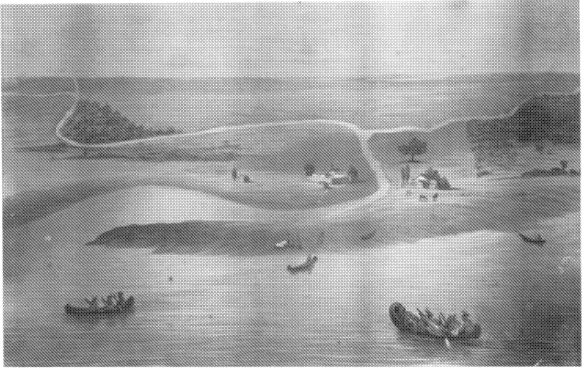

Chicago is forever changing: The prairie and portage give way to settlement, which in turn becomes a city that seems to insist on reinventing itself every decade. But there is at least one constant throughout the citys history. Chicagos central location makes it a place that allows for the easy movement of people and goods. So the early Native Americans utilized trails and canoes while a later generation of area residents drives the expressways, traffic permitting.

And yet there is more to Chicago than work and exit ramps. This is, after all, where Carl Sandburg found, The fog comes/ on little cat feet and By night the skyscraper looms in the smoke and the stars and has a soul. It is only natural that such a city would choose a design no less beautiful than practical in building a three-thousand-foot long pier for commerce and recreation.

Chicagos first permanent resident sensed the commercial possibilities of an area located at the base of the Great Lakes and within an easy portage of the Mississippi River system. Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, a Haitian emigre, arrived in the 1770s to establish a trading post. Eventually, du Sable erected a complex of nine buildings that stretched a quarter of a mile east and north from the mouth of the Chicago River, to what is now State Street. Du Sables trading post also served as a center for community. Here Europeans and Indians shared company as they made a living in the place named for the wild onion or skunk grass that flourished along the banks of the river.

Du Sable left the area in 1800. According to some reports, he hoped to become chief of his wifes people, the Pottawatomie. In any event, the founder did not get to witness the growth of the settlement he had begun. Chicagos development continued as the United States government established a formal presence with the construction of a fort in 1803. The installation was named for Secretary of War Henry Dearborn.

As du Sable and the native peoples had earlier, the American government understood that the junction of lake, river and plain created an important transportation hub. Fort Dearborn, located on the south bank of the river across from du Sables compound, was abandoned during the War of 1812 and rebuilt in 1816. When the garrison pulled out a final time in 1836, Chicago was only two months away from incorporating as a city and already anticipating the benefits of its first great transportation project.

The United States indulged in a peculiar fad the first half of the nineteenth century; it was a kind of canal craze that led to 3,326 miles of construction around the country, mostly between 1824 and 1840. People just had to dig, if perhaps for no other reason than to copy the success of De Witt Clinton and the Erie Canal.