Copyright 2014 by Andrea Quynhgiao Nguyen

Photographs copyright 2013 by Paige Green

Illustrations by Betsy Stromberg and Andrea Nguyen

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nguyen, Andrea Quynhgiao.

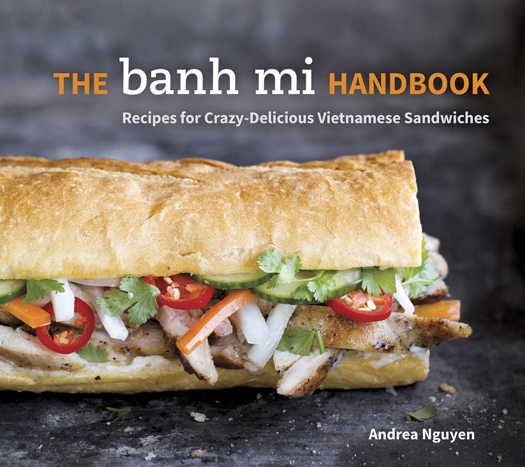

The banh mi handbook : recipes for crazy-delicious Vietnamese sandwiches / Andrea Quynhgiao Nguyen ; photography by Paige Green.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-60774-533-4 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-60774-534-1 (ebook) 1. Cooking, Vietnamese. 2. SandwichesVietnam. I. Title.

TX724.5.V5N469 2014

641.59597dc23

2014002924

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-60774-533-4

eBook ISBN: 978-1-60774-534-1

Prop Styling by Tessa Watson

by Ariana Lindquist.

v3.1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

S OME PEOPLE LIKE TO BAKE PIES. I LOVE TO MAKE sandwiches. Ive tinkered with them since elementary school. Our family often started the day with Vietnamese sandwiches. My mother would set out baguette or sliced white bread, butter, Vietnamese ( gio lua ), and black pepper. Each person was responsible for toasting his or her bread and assembling a simple banh mi.

Off to school I went, fueled by the combination of protein, fat, and carbohydrates until lunchtime, when Id tuck into a bologna or liverwurst sandwich that Id packed for myself. In the mid-afternoon, Id come home and make a sandwich snack, experimenting with luncheon meats, saltine crackers, and margarine, popular foods of the 1970s. I was a chubby child.

On the weekends, our family often bought banh mi (pronounced bun mee) in the granddaddy of Vietnamese-American enclaves, Little Saigon located in Southern Californias city of Westminster. The two-for-one deals allowed us to score cheap sandwiches for our family of seven. They were a steal (three banh mi for $4!), albeit often made with poor ingredients and little care. We tracked and followed banh mi deals for months, trying different shops that lured us with banners advertising their discount offers. But after hearing my mother say, Tien nao cua nay (You get what you pay for) too many times, our family pivoted. We started making our own Saigon-style banh mi loaded with all the bells and whistles.

I practiced preparing mayonnaise while my sisters debated the sweet-tart balance in our daikon and carrot pickle. Mom crafted old-school Vietnamese cold cuts, many of which were wrapped in banana leaf that my brother cut from a tree in our front yard. She updated her pt via a Julia Child recipe, forgoing pork for chicken livers, which she saved from whole chickens she had prepped for other dishes. We encased our banh mi in excellent baguettes baked by Vietnamese immigrants whod settled nearby.

This book is my ode to banh mi, my first sandwich love. Its a crazy combination of ingredientslots of vegetable and some animal, a remarkable display of synergistic textures and flavors. The recipes showcase banh mis endless possibilities, with nods to the roots of Vietnamese cooking as well as the creativity that propels it forward. Take a look, and cook, and tinker.

what is banh mi?

Whenever you explore the streets of Vietnam or strip malls of a Little Saigon, a thousand snacks beckon. Sticky rice with coconut, tropical fruit smoothies, and deep-fried dumplings vie for your attention, but inevitably, if youre a sandwich lover like me, you succumb to the banh mi vendor. He or she may tantalize you with cold cuts, pickles, and baguettes beautifully displayed on a cart. Or perhaps the line of customers at a bustling banh mi shop piques your interest.

Why not? Everyone enjoys a well-crafted sandwich. And with banh mi, for a modest amount of money, you get to ingest Vietnams delectable history and culture. The bread, condiments, and some of the meats are the legacy of Chinese and French colonialism. The pickles, cilantro, and chile reflect Viet tastes for bright flavors and fresh vegetables.

The French, who officially ruled Vietnam from 1883 to 1954 but arrived as early as the seventeenth century, introduced baguettes to Vietnam. At first the Viets called the bread banh Tay (Western or French bread; banh is a generic term for foods made with flours and legumes).

banh mi or bnh m ?

On March 24, 2011, banh mi was added to the Oxford English Dictionary . You dont have to italicize it anymore!

It was mainly associated with French foods such as bo , pho-mat, and bit-tet Vietnamese pidgin terms for French beurre (butter), fromage (cheese), and bifteck (beef steaks). By 1945, the bread had become commonplace enough for its name to switch to banh mi, literally meaning bread made from wheat ( mi ). Dropping the Tay signaled that the bread had been fully accepted as a Viet food.

People like my parents, born in 1930s northern Vietnam, snacked on freshly baked, fist-shaped rolls simply adorned with salt and pepper. When my father could afford it, hed spend a few extra cents to add a smearing of liver pt. My mother was drawn to a vendor who strategically positioned himself outside the school she attended. Most of the sandwiches made in northern Vietnam at that time were simple affairs, just bread, meat and seasonings, without any vegetable additions. That purity contrasted with the action in the south, particularly in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City), where cooks were concocting fanciful renditions, reflections of their freewheeling attitude and living-large lifestyle.

My fathers eighty-something-year-old friends recall that around the early 1940s, Saigon vendors started offering banh mi thit nguoi , an East-meets-West combination of cold cuts stuffed inside baguette with canned French butter or fresh mayonnaise, pickles, cucumber, cilantro, and chile. Maggi Seasoning sauce, a soy saucelike condiment likely introduced by the French, was the condiment of choice for adding savory depth. Somewhere along the line, the term banh mi came to signal not only bread but the ubiquitous sandwich.

Reunification of North and South Vietnam via the communist takeover in 1975 resulted in a mass exodus of refugees, many of whom settled in North America, France, and Australia; the United States is home to the largest Vietnamese population outside of Vietnam. Those who came from Saigon and the surrounding areas brought fond memories of Saigon-style sandwiches and yearned to savor them once more, and banh mi shops, bakeries, and delis sprung up in response.

Decades after refugees and immigrants brought banh mi to America, the customizable, affordable sandwich is known far beyond the borders of Little Saigon neighborhoods. Modern banh mi shops like Baoguette in New York, Baguette Box in Seattle, Bun Mee in San Francisco, and Saigon Sisters in Chicago crank out sandwiches for downtown professionals and hipsters alike.