MY LIFE OF LANGUAGE

MY LIFE OF LANGUAGE

A MEMOIR

Paul W. Ogden

Gallaudet University Press

Washington, DC

Gallaudet University Press

Washington, DC 20002

http://gupress.gallaudet.edu

2017 by Gallaudet University

All rights reserved. Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

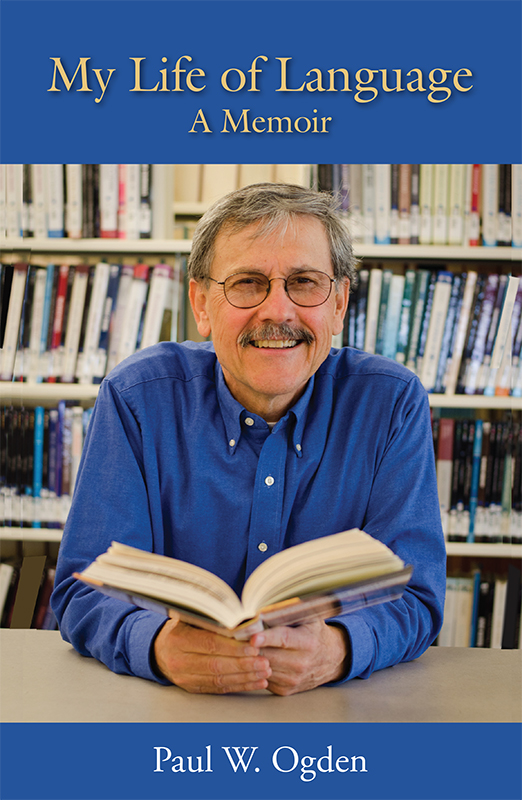

Cover photo courtesy of Stefani Santos.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ogden, Paul W., author.

Title: My life of language : a memoir / Paul W. Ogden.

Description: Washington, DC : Gallaudet University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017039434 | ISBN 9781944838140 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781944838157 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ogden, Paul W. | Deaf--United States--Biography. | Teachers of the deaf--United States--Biography. | Deaf--Education--United States.

Classification: LCC HV2534.O43 A3 2017 | DDC 371.91/2092 [B] --dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017039434

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

To the Reverend Dunbar H. Ogden, Jr. He often found it challenging to communicate verbally with us, his deaf sons. Yet he taught us to be comfortable with everyone and compassionate toward everyone, regardless of race, education, disability, and religion.

I HAVE BEEN profoundly deaf from birth. For nearly that long, it seems, I have also been a professional educator of deaf students. Nothing gives me the same sense of satisfaction as guiding, teaching, and advising young deaf people who are finding their way in the worldunless it is helping those who care about, work with, and are invested in the lives of these same young people.

My own journey as a young deaf person led me to this passion. The trials and triumphs of my early years, at a time when society often looked on deaf people in ignorance or with shame, fueled a desire within me to try to make the path a little smoother for future generations. Now I am ready to share with you the story of those years and the lessons I acquired along the way.

The experience of being deaf is profound, one that cannot be described in a single word or phrase. Rather, it is a range, a spectrum of conditions. The term deaf is applied to people who are profoundly deaf, with little or no hearing, to people who are only slightly hard of hearing, and to everyone in between. There is a similar range of approaches to educating and communicating with deaf people. This book is not just for those with a specific level of deafness or about promoting one of those education methods over another. It is for anyone with a connection to deaf or hard of hearing children and anyone with an interest in what it means to grow up deaf in a hearing world.

Successful communication takes many forms. We may bond with others through our ears, our eyes, physical touch, and more. Often our experience, our attitude, and even the environment make all the difference. A mealtime, for example, is a golden opportunity to make and maintain friendships. There is something in the shared experience of replenishing ourselves with a sandwich, a salad, a bowl of soup, or even a cup of coffee that breaks down barriers and encourages relaxed and heartfelt communication. I realized this when I was a young adult, a few years after my niece Stephanie and nephew Christopher were born. As they grew older, I noticed how difficult it was for me to connect with them when others were around. I decided I would take one or the other out to lunch or dinner during my visits, just the two of us. At these meals, we talked for hours about people and events in their lives, a practice they both appreciated and that we continue to this day. We had found a path to high-quality communication.

I was in graduate school when I spied a poster on the wall of a faculty members office. It depicted a painting by Monet, The Artists Garden at Vtheuil. Immediately, I fell in love with the pastoral scene. I delighted in the sensation of being in the garden, of feeling embraced and supported. It reminded me of the Garden of Eden, a place where life begins, a place where people live in harmony and peace. It also brought back memories of my familymy mother, father, and brothers, who lovingly gave me my first lessons in communication. As I grew up, I sensed that all of us seek such a garden, a place where we can understand and be understood, a perfect world for living and loving. For me, it depicts a world of perfect communicating.

All of us are still on the path toward understanding and perfect communication. Perhaps this book can be another stepping-stone for you, whether you are hearing or deaf. I hope the following pages give you joy, laughter, hope, guidance, sensitivity, encouragement, and inspiration.

MANY PEOPLE along the way have coaxed and urged me to finish this work. They have been extraordinary coaches who love words. There are more people to thank than can be recognized here. Among them: Brian Riley, Jim Lund, Kathy Yoshida Doerksen, Pamela McCallon Warkentin, and my students, staff, and faculty colleagues at California State University in Fresno. They listened patiently to my life stories and responded from the heart.

Special appreciation goes to my brother Dunbar and his wife, Annegret, for their enthusiasm and moral support for not only this book but all my book projects. Behind the work, and within it, lives the inspiration and the memory of my parents, Dunbar and Dorothy Ogden, and my brothers David and Jonathan. The person who has been my true foundation is my wife, Anne Keenan Ogden. Her love and patience have sustained me through the writing process and cheered me up through all the months and years. The best deal we have for our passions during very hectic times is that she quilts and travels while I teach and write books.

My deep appreciation goes to Ivey Pittle Wallace at Gallaudet University Press. With her rigorous crafting and shaping as an editor, I have gained confidence in the words on the page. Very special thanks go to these people for their sharp proofing skills: Kim Holly, Ellen Morse, and Marilyn Weinhouse, whose insightful comments also added clarity to the manuscript. With her art photography on the cover, Stefani Santos invites the reader to open the book and read on.

IMAGINE YOU ARE standing behind an airport window, watching passengers deplane. Suddenly you see a young, wide-eyed stranger stepping uncertainly down the portable stairway, wrapping her jacket tightly around herself. This is the person youve been waiting for. She is a foreign exchange student on her first visit to America and you are her host.

When this new arrival reaches the airport, she glances around, taking it all in. You sense that she is nervous. You know she doesnt speak English, so you step forward to greet her with a smile and a welcoming hug. As you do, you feel the weight of your responsibility. Its up to you to introduce this young woman to her new world.

This is only a made-up story, of course. But for parents, teachers, and other family, friends, and professionals who are charged with raising and teaching deaf children, it is an apt illustration of what both sides will face. A young deaf boy or girl may often feel like a stranger in a foreign land, unable to grasp common language practices and pick up the simple but vital bits of information that allow us to easily connect and communicate. A parent or teacher, meanwhile, is this childs guide. If we are that parent or teacher, our task is to support, to encourage, and to teachto be a good host.

Many years ago, my parents faced this unexpected challenge. On the day I was born, my mother held me in her arms for the first time, gazed into my eyes, and confronted a sudden, shocking realization: that her newborn son might be deaf. The clue was the loose way I held my head, an indication I had no sense of balance. It is a common characteristic of babies with hearing loss, a sign my mother already knew well because my older brother Jonathan also is deaf.