B AREFOOT TO A VALON

ALSO BY DAVID PAYNE

Confessions of a Taoist on Wall Street

Early from the Dance

Ruin Creek

Gravesend Light

Back to Wando Passo

David Payne

Barefoot to Avalon

A Brothers Story

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

Copyright 2015 by David Payne

Jacket design by Elixir Design

Author photograph by Mathieu Bourgois

Page ix: Excerpt from Roth, Philip, The Counterlife . New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1986. Page 21: Excerpt from It All Comes Together outside the Restroom in Hogansville by James Seay taken from Seay, James, Water Tables . 1974 by Wesleyan University Press. Used with permission. Page 24: Excerpt from Burnt Norton by T. S. Eliot taken from Eliot, T. S., Collected Poems 19091935 . London: Faber, 1936, by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company; Copyright renewed 1964 by T.S. Eliot. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Page 43: Excerpt from Absalom, Absalom! by William Faulkner copyright 1936 by William Faulkner and renewed 1964 by Estelle Faulkner and Jill Faulkner Summers. Used by permission of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Page 65: The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock by T. S. Eliot was first published in Poetry magazine in 1915. All lines quoted are public domain. Page 70: excerpt from One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish by Dr. Seuss, and copyright by Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P., 1960, renewed 1988. Used by permission of Random House Childrens Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Pages 78, 124, 138: Excerpts taken from Jung, C. G., Memories, Dreams and Reflections . New York: Pantheon Books, 1963.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

Note from the author: Though this book is a memoir, Ive changed the names, residences and certain background details to preserve the privacy of characters who arent members of my immediate family.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8021-2354-1

eISBN 978-0-8021-9184-7

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

Contents

2000

2006

1975

2000

2006

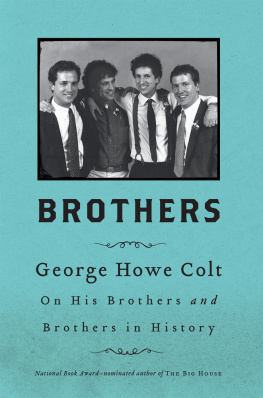

To George A.

In a way brothers probably know each other better than they ever know anyone else.

How they know each other, in my experience, is as a kind of deformation of themselves.

The Counterlife, Philip Roth

Prologue

In my earliest memory Im three years old, running down the hall of our old house in Henderson, North Carolina, a small, gray-shingled one in a stand of oak trees on a hilltop overlooking Ruin Creek. Im wearing my special cowboy outfit, black hat and vest with tinselly Charro trim. My mother has just come out of the bathroom, and we collide. Margaret, twenty-two, seems ageless, a film goddess from a prior era caught in close-up on the big screen at the drive-in. Her black hair is down and she wears a loose robe. As she sashes it, I note her swollen belly.

Youre fat! I cry gleefully, as though Ive caught her at some trespass the way she frequently does me.

Margaret smiles as though about to share a wonderful surprise.

Youre going to have a new little brother or sister, she tells me.

I stand there, smiling vacantly. In my head, a static noise like the TV after midnight station sign-off, when the Indian Head test pattern appears after the singing of the anthem.

I take my silver six-gun, place it against her stomach and pull the trigger.

Bang! I say and run off laughing.

I

2000

And the Lord said unto him... What hast thou done? The voice of thy brothers blood crieth unto me from the ground.

Genesis 4:10

O n November 7, 2000, at around 8:30 in the evening, as the polls are closing in the East and the networks give the early edge to Gore, I lock the door of our house in Wells, Vermont, and place the key, by prearrangement with the realtor, in a Tupperware container under the back steps. In the dark front yard, a twenty-six-foot U-Haul truck sits low on its suspension, its lights angled toward the culvert at the top of our steep gravel drive. The high beams splash a stand of birches and lose themselves in the thick woods on Northeast Mountain, which looms over the protected meadow I bought eleven years ago and where I built the house Im leaving.

My 1996 Ford Explorer idles nearby, and I can see George A., my brotherforty-two and heavy, his thick black hair and mustache sable-frostedsmoking in the greenish backwash from the panel. On the hitch is the twelve-foot trailer I didnt think wed need when he flew up last week to help. Stacy, my wife, is already in North Carolina with our two-year-old daughter and our infant son. Having the children underfoot, weve agreed, would make a stressful job more difficult.

For eight days, George A.s gone with me room by room and shelf by shelf, taking the Wells house apart, down to the wild turkey feathers and New York City restaurant matchbooks, the loose change scattered at the bottoms of the drawers.

My original plan had us leaving after lunch on Sunday, two days ago, November 5. By midnight Sunday night wed just started to attack the bookcase in the great room I drew and built with nine-foot sidewalls and a vaulted ceiling and a loft and barn sash windows in the gables. On a ladder, pulling volumes down, I handed George A. the family pictures and fragile ware, and hecrossed-legged on the plank pine floor in soiled white socksswaddled them in Bubble Wrap, tearing ragged swaths of masking tape and fighting with the roll. It seemed to me the tremor in his hands had worsened and the smudges beneath his eyes were darkerlike the eye grease he wore when he played ball beneath the lights on Friday nights in high school. The difference was worrisome.

It had been eight months, perhaps a year, since Id seen him. The last time I visited Winston-Salem, I caught the smell of George A.s cigarettes as soon as I walked in the front door of Margarets town house, where I found her alone in a pool of lamplight in the small front parlor, working on a book and a glass of Pinot. Shewhod stopped smoking years beforelooked up at me with a grievance in black eyes that were George A.s eyes, toosomething bemused and sad and angry and exhausted, resolved above all else to see it throughwhile George A. chain-smoked in the larger den in back and sipped a beer and laughed his croupy laugh at South Park . Once a top producer in the Winston office of Dean Witter Reynolds, married with two sons in private school, a BMW and a house in the tony district, Buena Vista, George A. had been there with Margaret for nine years. The tension was so thick a knife would not have scratched it. During the day when Margaret was at work, he smoked and watched the back crawl of the ticker tape on the financial channel. At night when she came home, Margaret cooked his supper and took it to him on a tray, and when hed eaten, George A. left it for her on the kitchen counter and shed tiptoe up and kiss his cheek and tuck a $10 or $20 in his pocket as he headed to the barno longer the one favored by the hotshot brokers with their Gordon Gecko haircuts and spiffy bracesbut to Ritas, a humbler establishment in Clemmons, an exurb twelve miles distant, where Margaret had lived with Jack Furst, her second husband, after they were married.