Also by George Howe Colt

The Big House: A Century in the Life of an American Summer Home

November of the Soul: The Enigma of Suicide

ELLEN M. AUGARTEN

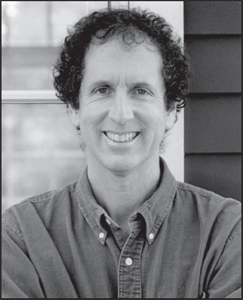

GEORGE HOW ECOLT is the bestselling author of The Big House , which was a National Book Award finalist and a New York Times notable book of the year, and November of the Soul: The Enigma of Suicide . He lives in Western Massachusetts with his wife, Anne Fadiman, and their two children.

MEET THE AUTHORS, WATCH VIDEOS AND MORE AT

SimonandSchuster.com

JACKET DESIGN BY STEVEN MARCATO

JACKET PHOTOGRAPH BY SCOTT THODE

COPYRIGHT 2012 SIMON & SCHUSTER

Thank you for purchasing this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

For Harry, Ned, and Mark

Contents

Chapter One:

The Colt Boys

Chapter Two:

Good Brother, Bad Brother: Edwin and John Wilkes Booth

Chapter Three:

The Fallout Shelter

Chapter Four:

Brother Against Brother: John and Will Kellogg

Chapter Five:

Baseball

Chapter Six:

Brothers Keeper: Vincent and Theo van Gogh

Chapter Seven:

Under the Influence

Chapter Eight:

Brothers, Inc.: Chico, Harpo, Groucho, Gummo, and Zeppo Marx

Chapter Nine:

Aerogrammes

Chapter Ten:

The Lost Brother: John and Henry David Thoreau

Chapter Eleven:

The Colt Men

Chapter One

The Colt Boys

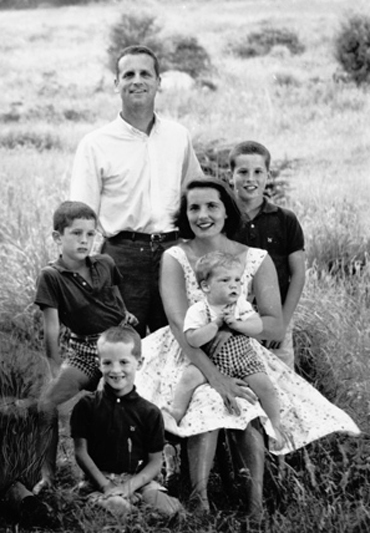

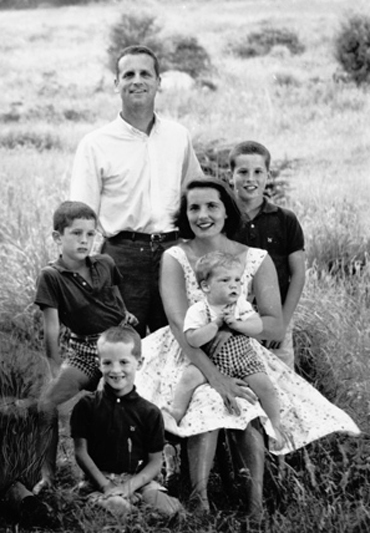

I f the handful of black-and-white snapshots that remain from my childhood is any indication, its a wonder I didnt end up with a permanent crick in my neck from literally and figuratively looking up to my older brother. Harry was born twenty months before me, and I worshiped him with an intensity that must have been both flattering and bewildering to the worshipee. I didnt want to be like Harry; I wanted to be Harry. I cocked my coonskin cap exactly the way he did when we played Daniel Boone; I made the same pshew-pshew sounds he did when I pulled the trigger on my silver plastic six-shooter; I punched the pocket of my baseball glove every time he punched his. When he woke me in the middle of the night one Christmas Eve and invited me downstairs to open presents while our parents slept, I followed. When he said he could help me get rid of my loose tooth, I let him tie it to the playroom doorknob and slam the door. He was my older brother and I would have agreed to anything he proposed; I would have followed him anywhere. And so, one spring evening not long before I turned six, as we lay in our matching twin beds, when Harry suggested that we run away from home, I said yes.

The following morning before dawn, I woke to find him standing next to my bed in his pajamas, clutching to his chest the gray metal strongbox in which he kept his baseball cards. I tiptoed behind him down the back stairs, through the kitchen, and into the garage. Harry opened the front door to the old blue Ford, climbed in, and shimmied over to the drivers seat. I scrambled up next to him. We sat awhile in silence before he unlocked the strongbox and offered me some of the saltines with which he had filled it the night before. (To make room, he had left behind all but his most precious Red Sox cards.) We chewed our crackers and stared through the windshield at the closed garage door. I dont remember what we said, or indeed whether we said anything at all. I dont remember wondering where, if anywhere, we were going, or how far we could get in our pajamas, or what we would eat when the saltines ran out. I certainly didnt ask my brother. Because I believed Harry could do anything, I wouldnt have been surprised if the car had somehow started, the garage door had opened, and wed sailed off down Village Avenue, our quiet, tree-lined street in suburban Boston, and into the sky.

* * *

It never occurred to me to ask my brother why we were running away. Ours was not the kind of home from which most people would have thought it necessary, or even advisable, to run away. We lived in a comfy old brown house equipped with a corrugated cardboard fort big enough to stand up in; enough wooden blocks to construct several castles simultaneously; a banister to speed our journey from the second floor to the first; and a bathroom in which every fixturesink, toilet, and tubwas jet-black, a color scheme so unusual that neighborhood kids were always knocking on our door, asking to use the facilities. We had a backyard big enough for games of catch and a sprinkler to run through on hot summer days. Beyond our fence lay a world that seemed designed for a six-year-old boy: houses close together to maximize candy collection on Halloween; enough kids within shouting distance to field a baseball team; sidewalks that could get our bikes every place worth getting to, their curbs so eroded by generations of Raleighs and Schwinns that we didnt have to dismount when crossing a street; and a huge chestnut tree that provided ammunition for fights, pretend money for card games, and the sheer pleasure of peeling off the rubbery, lime-green skin to uncover the nut within, shiny and polished as a violin.

Best of all, within a stones throw of our houseif Harry was doing the throwingthere were three places that made our otherwise tame neighborhood seem as thrilling as the wilderness depicted on any explorers map. Four houses to the east lay the Norfolk County Jail, an ivy-covered granite hulk in which, our mother told us, two prisoners with Italian names I could never remember had been imprisoned before being sent to the electric chair in 1927, an event whose macabre allure still lingered in the air as I hurried past on my way to the library thirty-five years later. (I could never understand why bad guys were always sent to the electric chair, which made it sound as if the post office were somehow involved and begged the all-important question of what happened after they reached their destination.) Across the street from the jail lay the graveyard, where we played freeze tag, hide-and-seek, and war, taking care not to step on the bulges in front of the lichen-embossed headstones, bulges we assumed were the bellies of the dead. A block to the south of us, the tidy lawns gave way to a morass of vines and skunk cabbage we called the swamp, an outpost of botanical anarchy that in well-manicured Dedham seemed as exotic as the Black Lagoon from which the proverbial Creature emerged, and in whose tea-colored water wed wade in search of smaller but equally slimy creatures. These three landmarks allowed us to believe that we lived in a dangerous world, a world in which an escaped convict, a vengeful ghost, or a hideous monster might appear at any moment. I remember watching Swiss Family Robinson and being impressed that the island on which they had shipwrecked somehow encompassed mountains, waterfalls, beaches, caves, lakes, and quicksand (a wealth of natural wonders ecologically unlikely to be found in one place, I later realized). With its prison, its graveyard, and its swampwhich, I felt sure, contained at least a dollop of quicksandour neighborhood had been no less blessed.

Even without these attractions, I wouldnt have been inclined to run away from home. Dedham was the first place my family had lived long enough to call home. Our father was a businessman, and whenever he was promoted, we moved to a new town. (In those days, you went where the company sent you or you wouldnt be with the company for long.) Before Dedham, we had lived in Pittsburgh, El Paso, and Philadelphiathree different places in five years. We had been in Dedham for more than two years, the longest we had ever spent in one place, and I assumed we would be there forever. Dad built us a sandbox and installed a swing set. He and Mum spent Sunday afternoons on their hands and knees, putting in a brick patio. They planted a dogwood tree and a bed of pachysandra. For the first time, our family, too, seemed to be putting down roots.

Next page