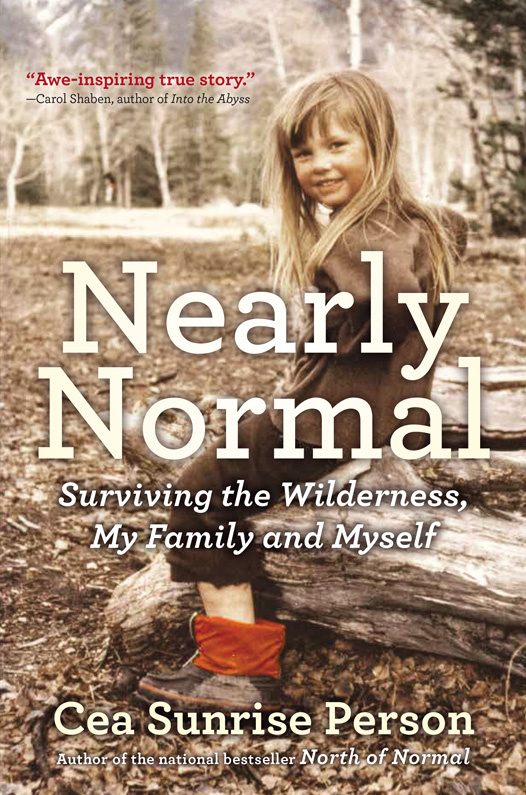

1973

Kootenay Plains, Alberta

W hen folks came to visit us at our first wilderness home in central Alberta, they were provided with little more direction than to turn right immediately after a particular curve sign on the David Thompson Highway. They would then drive down a dirt road for a short distance and park near a footbridge at the North Saskatchewan River, where they would load their belongings on their backs and begin the five-mile hike in to our camp.

Here the beauty of the stark, yellow poplar leaves against the snow-topped mountains and massive open sky looked almost too picturesque to be real. Treading a log bridge across the Siffleur River, they would notice the hoodoos jutting along the bank like jagged stone fingers. Smaller wildlife abounded along the trailrabbits, chipmunks, porcupines, eagles, woodpeckers and grouseand on a good day, a bear or moose might wander into view. Farther inland, the variety and number of trees thickened into forest, where the smell of the air changed to include pine and moss. The silence was punctuated only by twittering birds, rushing water and leaves crunching underfoot.

By the time visitors walked into our camp, they could well appreciate why Dick Person had chosen this particular part of the world to move his family to. And by the time they tasted a wild game meal cooked by my grandma Jeanne, succumbed to the soothing rhythm of Papa Dicks rambling teachings and sampled some of my familys home-grown against a background of Jimi Hendrix, theyd feel like they never wanted to leave.

Perhaps the counterculture dream would have remained intact for Fred if it werent for my uncle Dane. Then again, considering our complicated family dynamics, maybe Dane was just the biggest festering wound among many smaller ones.

I dont remember Fred. When he came to stay with us, I was three years old. He was one of many summer visitors who came to our tipis during that year and the year before and the year after, eager to meet my grandfather and learn our off-the-grid ways. I say my grandfather because even though my mother and two aunts and Grandma Jeanne and I were there, it was always Papa Dick they flocked to. Some suggested he might have missed his calling, that he had the rare brand of charisma found in a cult leader and could have been more than a wilderness guide who extolled the virtues of wild game meat and shit pits and life in the bush in minus-fifty-degree weather in canvas tipis. But my grandfather had none of the zeal required to assemble a cult following. The only religion he preached was nonconformity.

This was Freds fourth visit to our tipis. Hed been introduced to my family by David, an experienced bush guide and regular around our camp. Fred didnt think there was a person in the world who loved the outdoors as much as David did, until he met my grandfather. Here was a man whose beliefs left no room for other peoples opinions, and though Fred sometimes found this hard to take, he also admired it. With my grandfather, he always knew just what to expector so he thought.

This time when Papa Dick greeted Fred, David, and Freds brother at the footbridge to accompany them into our camp, they were met not with blissful silence but by the grinding noise of a chainsaw. My sons building a cabin, my grandfather said by way of explanation. Just came up from Ponokaarrived here last month, and hes been going at it ever since.

Fred nodded but didnt comment. My grandmother had mentioned to him once that they had a son with mental issues, but the sons presence wasnt as surprising as the fact that Dick was allowing a cabin to be built at all, much less with a chainsaw. Fred knew my grandfathers views on such things. Papa Dick had chosen to live in a tipi because he believed the thin walls brought one into closer alignment with nature and also because the circular structure encouraged the flow of energy, while square buildings blocked it with their man-made angles and thick walls. And other than the old VW bus my grandfather occasionally drove into town for supplies and the car battery he used to power his tape deck, he didnt believe in technology. Batteries, electricity and gas-powered motors changed the molecular charge of the environment, he explained, which was why he himself had built the structure for three tipis and all of our familys furniture using nothing more than a handsaw, an axe and a hammer.

As if reading Freds mind, Papa Dick glanced in the direction of the noise. I dont like it either. But at least hes not building at the camp. I wouldnt allow it. Hes up Siffleur Valley a bit. He paused, scratching his head through his wool cap, then dropped his voice slightly. And hes, well... off his meds.

Ah. An unexpected visit, then, Fred responded through a plume of frozen breath.

Everything Grandma Jeanne had told him was coming back to him nowthe paranoid schizophrenia, the years at Ponoka Mental Hospital, and the final straw that had sent him there: Dane snatching me from my mother when I was a baby and locking me in the cellar with him.

You could say that. And theres not much talking to him. In fact its best to not try at all. Heres the thing... Papa Dick met the mens eyes in turn. Danes got a bow and arrow, and hes a good shot. Then he stepped closer and pressed his rifle into Freds hands. Dont be afraid to use this. If you feel threatened, dont hesitate to shoot first.

Fred stared at him as a jumble of questions whirled in his head. But Papa Dick had already turned to lead the way back to camp, leaving Fred and his companions exchanging uneasy glances in the fading daylight.

After they arrived at our camp, the first order of the evening was to organize accommodations. Since the frozen ground of late fall made tenting a rather miserable option, Mom and I decamped to the cooking tipi so Fred and his companions could sleep in ours. At that point, Mom and I were still a couple months away from having a real wood stove, so in the meantime our tipi was outfitted with the Guzzler, which wasnt really a stove at all but a rusty barrel with a hole cut out of it. The stove smoked incessantly and lent little warmth.

After shivering in his sleeping bag all night, Fred would come over and help Mom set up breakfast. The cooking tipi wasnt much better, because to make room for the stoves chimney, the flaps needed to be left wide open, allowing into the tipi a steady cascade of snow.

Kids. They dont feel the cold, do they? Fred commented to Mom, watching as I ran outside coatless.

Probably just used to it. Its pretty much all shes ever known.

Fred tried being friendly to me, but I wasnt having it. Most men who visited our camp ended up doing the screwing with Mom, which meant Mom paid more attention to them than me, and attention was already hard to come by. But I neednt have worried about Fred. The real threat to my security was Randall, who came by regularly attempting to woo Mom back into his bearskin bed. Randall was the chief of the Cree Indian tribe across the river, and he and Mom had been going hot and cold practically since wed moved here. Once, at the sight of Randalls face and while Fred looked on, I threw myself into Moms lap and screamed as if I were being mauled by a bear. Fred was twenty-two years old and hadnt paid much attention to kids before, but I made myself pretty hard to miss. While I cried, he held my Suzie Doll out to me and tried to coax me to play. I ignored him, but the next day when everyone gathered for supper in the cooking tipi, I let him sit next to me.