CONTENTS

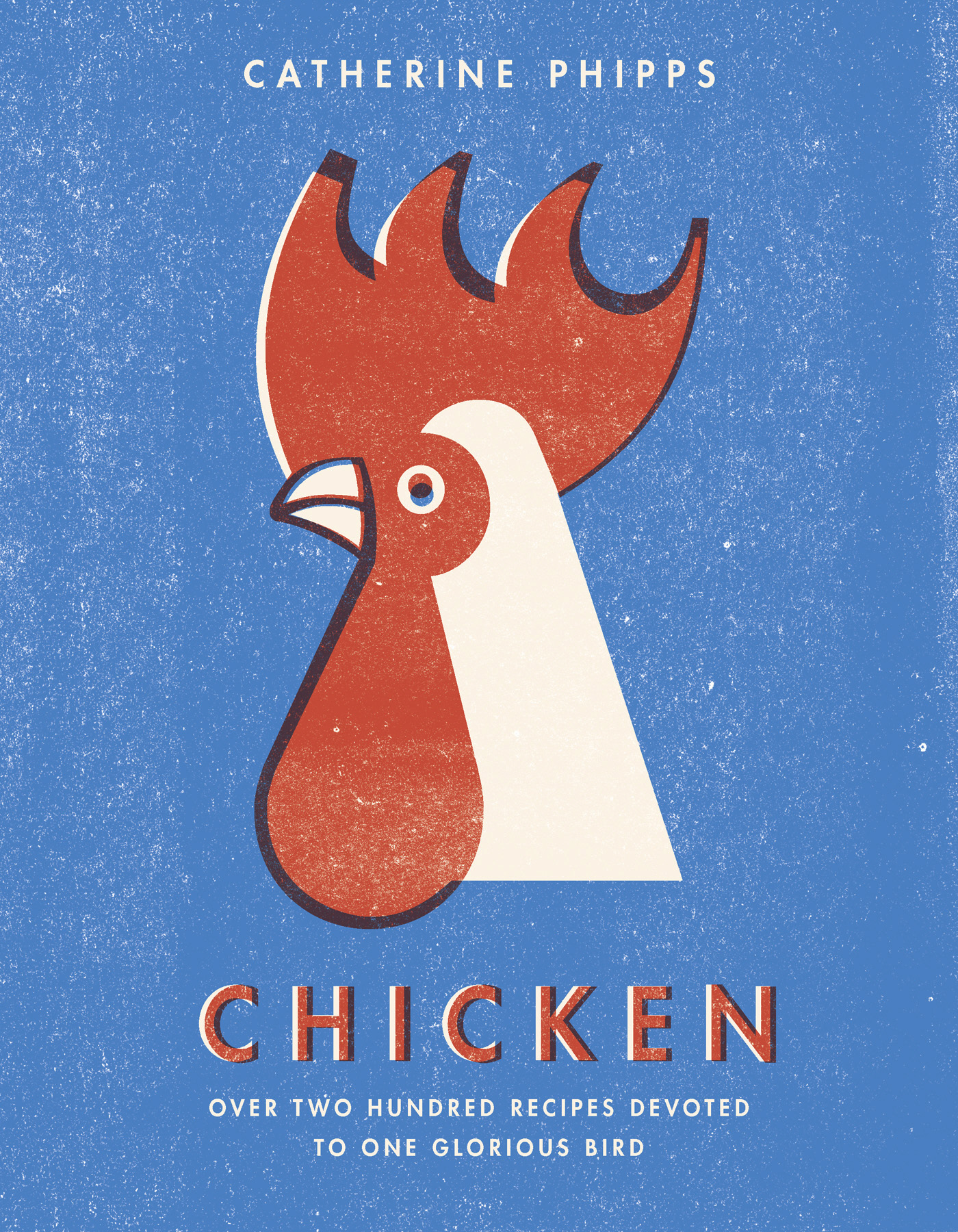

About the Book

Chicken tonight?

Fried, flambed, roasted, barbecued, smoked, stewed, grilled, put in a sandwich or made into soup the versatility of chicken knows no bounds and this book contains every recipe for chicken that you will ever need.

From Double-crusted Chicken Pie, the Best Roast Chicken and Chicken Pt to Baked Italian Meatballs, Confit Chicken, Butter Chicken and Chicken in a Mountain there are recipes old and new to tempt and inspire you.

This is a culinary world tour, with over 200 recipes using a vast array of flavours, and a chicken lovers feast.

About the Author

Catherine Phipps is a columnist for the Guardians Word of Mouth food pages and a freelance food writer. She is the author of The Pressure Cooker Cookbook. Catherine lives in West London with her family.

INTRODUCTION

Poultry is for the cook what canvas is to the painter.

Brillat-Savarin

Everyone loves chicken, right?

Homer Simpson

I remember the first time I roasted a chicken. I was around seven or eight and my mother was ill and directed operations from the sofa. I cooked the whole meal: chicken smeared in butter on a bed of onions and thyme, roast potatoes, vegetables, even proper gravy. I dont remember much about eating it, but I do remember being proud of myself and feeling as though Id saved Sunday. Because in our house, a Sunday without a roast especially a roast chicken was no Sunday at all. Even now, its my idea of home.

I may not remember sitting down to the meal, but I know exactly how it would have tasted, because Ive been cooking it on a regular basis ever since. I love everything about the taste and texture of proper chicken, no other meat gives quite so much variety in both. Theres that strong savoury quality, balanced by the merest hint of sweetness and if decently reared with outdoor access a touch of gaminess, too. I especially love the crisp and sticky skin and the soft, tender texture of the brown meat, but even the slightly stringy breast meat is made worthwhile as it can have such an intensely umami quality it can make the mouth pucker and water.

A decent chicken has always been one of my favourite things to eat and I was taught from an early age to appreciate its usefulness in the kitchen. My parents believed strongly that I should understand the origins and value of the food we ate and my mother ensured I knew how to cook it. Chickens were the first animals we kept, for both eggs and meat. They were my responsibility as soon as I was deemed old enough and despite the fact that I loved the homely cluck the chickens made whilst they grubbed around the garden (I still love that sound and the feeling it evokes), I was also quite happy to eat them when the time came. And of course, that time did come with an inevitable regularity. Roasters usually young cockerels were allowed to strut around until fattened up (a bit older than spring chickens or poussins), then they were dispatched, along with any old and tired layers.

Our home-reared chickens were supplemented by birds from local producers: farmers wives or retired farm labourers who raised small flocks for hen money all year round, but especially at Christmas when we would eat cockerel rather than turkey. We knew where our chickens came from, what they had been fed, how they had been slaughtered, all things I do my best to find out about the chicken I eat today. And in this age when intensively farmed chicken is the norm and people are becoming more and more disconnected from their food, this can be hard to do. Hard, but not impossible and it neednt break the bank either.

Cooking and eating a whole chicken was an event, a special treat no matter how many times we ate it on a Sunday. But leftovers were extensive and old layers the boiling fowls were also treated with respect. They were slowly and gently poached (boiling is a bit of a misnomer) to extract the full amount of flavour and goodness for nourishing broths, and to soften the perfectly edible but rather stringy meat. Stock from poaching or from saving up old carcasses was always plentiful, so the flavour of chicken was carried through into many of our meals.

I realise now that this way of cooking using the complete chicken in as many ways as possible has informed my whole approach to food. It was economical, being very nose to tail or beak to claw in this case. We didnt use the cockscomb or the feet (and I still dont today), but ate just about everything else. What this meant was that chicken could often be used to enhance, add depth to or transform an otherwise meatless meal, whether by frying in schmaltz (rendered chicken fat, as nutrient-rich and well-flavoured as duck or goose fat); using a well-balanced chicken stock, sometimes with some leftover meat, in a soup, stew, rice or pasta dish; or simply adding some shards of well-browned chicken skin as a garnish. Consequently I have never adopted the modern and deeply uneconomical way of buying chicken pieces (especially chicken breasts), but have always, even during my most impecunious periods, bought a whole bird and made it last at least a week, longer if I use the freezer. The recipes in the book reflect this.

I have always known that this is a very economical way of eating chicken, but it is only quite recently that I realised how traditional it is, too. While researching this book I found that, when looking specifically at British cookery books, before 1950 there are few chicken recipes beyond ways to roast, stew and occasionally grill. The other emphasis is on dishes using cooked chicken, i.e. leftovers. There are one or two dishes using chicken pieces, such as an early curry recipe in Eliza Actons Modern Cookery for Private Families, but these are largely ancillary.

In the last 60 years or so, our culinary landscape has changed almost beyond recognition and the way we eat chicken is at the heart of this. We now eat more chicken than any other meat. This really took off in the 1950s, when two things happened. Firstly, chickens became widely available again after World War II and we started raising them intensively. Secondly, and more positively, this was when our outlook broadened. The world shrunk, we travelled more and we discovered new cuisines; the cookery book market, spearheaded by the Penguin list, expanded beyond recognition to accommodate this. We came to value chicken more for its versatility, for its ability to work with so many different flavours.

There are good and bad aspects to this. On the one hand, I love and am still quite excited by the universality of chicken. It is central to virtually every omnivorous culture and no other meat can claim this. It means that for those of us who always thirst for something new to try (and lets face it, the average Westerner is a culinary magpie, constantly wanting to be dazzled by the latest, just-discovered cuisine), chicken provides us with the way in, the point of familiarity in an otherwise strange new world. The downside is that chicken has become ubiquitous, most of us accepting the modern trope that it will work with everything. What is wrong with this is that instead of being valued for its flavour, chicken has been relegated to the position of flavour carrier. Homer Simpson may well say we all love chicken. Brillat-Savarin may also say its a blank canvas. I say that many of us now treat it with indifference and throw anything at it, without discrimination. For me, this is completely missing the point of chicken; we may as well be eating soya chunks. I feel strongly that if I cant appreciate the pure chicken-ness of chicken in every meal in which it appears, I shouldnt be eating it at all.