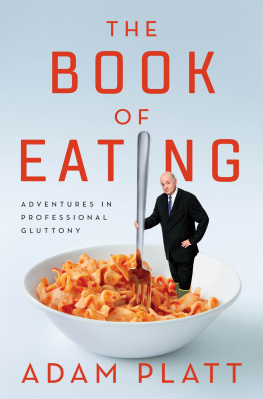

A s anyone who writes about their dinner for a living knows, there are few things more subjective, or prone to myth and exaggeration, than the distant memory of an excellent meal. The same is true of a memorably horrible meal, of course, the legend of which invariably grows in horror and awfulness with each retelling. This memoir is the pieced-together record of thousands of such idealized, half-remembered eventsof family dinners and picnic luncheons and summer goat roasts, which may or may not have actually been as novel or as nourishing as they seem to me now. Its a memoir of dumpling feasts and Peking duck dinners in the far-off places where I found myself living as a child, and of the kinds of strange things you come across, and even seek out, as a professional eater, like grilled chicken uterus, or raw horse sashimi, or the icy dabs of poisonous blowfish sperm, which I ingested in a state of not-so-quiet horror for a magazine story many years ago.

Ive attempted to re-create these episodes as I remember them, and if I cant remember them, Ive relied on the memories of others. Special thanks to my father for his descriptions of long-ago meals and restaurants, and whose eclectic love of a good meal set the tone for my career as an eater. Thanks to his brother, Geoffrey, and to their cousins, Charles Platt and Frank Platt, the family gastronome, for attempting to reconstruct the dining habits of their eccentric Yankee ancestors, the Choates and the Platts. Thanks to my brothers, Oliver and Nicholas Jr., for racking their brains about our long-ago food adventures in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Tokyo, and to my mother, who spent many patient hours trying to recover the culinary nightmares from her sheltered WASP upbringing, many of which shed managed to suppress for decades.

Ive written more than I probably should about my diets, the various dining foibles of my daughters and wife, and the strange eating habits of the professional glutton, and portions and snippets of several of these articles and reviews, many of which appeared in New York magazine and on the magazines website Grub Street are reproduced and expanded on here. Special thanks to my first editor at New York, Meredith Rollins, who had the daring, slightly cockeyed idea to turn me into a restaurant critic, and to Mark Horowitz and Caroline Miller for making that strange dream a reality. Thanks to Klara Glowczewska for sending me on many pleasurable junkets during her tenure at Cond Nast Traveler, and to Pam Wasserstein, the great Adam Moss, and David Haskell for their beneficent, hands-off support during my time as the chief eater in residence at New York magazine. Thanks to my longest-serving, longest-suffering editor, Jon Gluck, for shepherding a thousand end-of-the-year monsters into print, and to my many other colleagues at the magazine and websiteNoreen Malone, Raha Naddaf, Anne Clark, Jody Quon, Alan Sytsma, and those dynamos of the food section Rob Patronite and Robin Raisfeldfor their support and guidance over the years.

Thanks to my agent, Suzanne Gluck, for exhibiting the kind of patience that high-powered literary professionals arent generally known for during the decade or so I spent not writing this book. Thanks also to Farley Chase for his advice on portions of the manuscript, and to Hugo Lindgren for his invaluable editing advice after gamely taking the time to grapple with the entire thing. Thanks to my occasional interns, Clare Platt, Sam Hawkins Sawyer, and Olivia Caldwell, who gamely made restaurant reservations using ridiculous fake names, diligently gathered any research I asked them for, and brought some sense of digital sanity to my disheveled, paper-strewn desk. Thanks to my diligent, long-suffering production editor at HarperCollins and to the wise, ever-cheerful Gabriella Doob at Ecco for calmly guiding this manuscript and its author to print through various stages of confusion and terror. And thanks, most of all, to Daniel Halpern, who had the idea for this memoir more years ago than either of us probably cares to remember, waited with a kind of biblical patience over the months and decades for the pages to slowly pile up on his desk, and once this confused jumble of thoughts and impressions had achieved a kind of critical mass, gave the thing a name and pronounced it done. For better or worse, none of us would be reading this book without him.

R emember to look for the lady wearing a very large hat, I think I hear my wife say, with a helpful, slightly wan smile, as I inspect my new jacket in front of the mirror in a nervous, slightly bug-eyed lather. One of us has read somewhere that in the mysterious Kabuki world of the professional restaurant critic, Gael Greene is famous for her extravagant hats. Hats are supposed to be Gaels calling card, her signature prop and pseudo-disguise. Over the decades, as the critic for New York magazine, shes been photographed sitting in the banquettes of grand restaurants, sipping flutes of champagne, peeking slyly out from under colorful wide brims of every design. Shes sported so many different varieties of headgear over the yearssummer straw hats, floppy felt hats, wedding hats, ship captain hats emblazoned with spinning globes and golden anchorsthat Ill later hear that the restaurant people (who tend to spot the only person in the room wearing a hat every time) sometimes call her Sergeant Pepper in whispered tones behind her back.

My new jacket is size 48 extra-long, or possibly even larger and longer than that. Ive just purchased it off the rack at a store called Rochester Big and Tall in midtown, which, in the summer of 2000, is where many of the citys prominent giantsbasketball stars, ox-shouldered linemen who play for the Jets and the Giants, even Rush Limbaugh himselfpurchase their fancy, Gulliver-sized threads. The jacket is boxy and coal black and looks like its been constructed out of yards of shiny black undertakers cloth. Id told the bemused salesman at the fatso store that I wanted a durable, sensible garment, something I could wear to polite restaurants and grow into if I gained an inch or two around the chest and belly. I wanted something in a dark color with the slightest hint of polyester sheen, a jacket that could be cleaned easily, when I stained it, discreetly, with streaks of Hollandaise sauce and steak fat.

I put on this giant, flapping undertakers garment, and Mrs. Platt and I both regard my looming reflection in the full-length mirror for a time, in studious silence. Im the nervous worrier of the family; my wife is the cheerful, optimistic one, always living life on the sunny side of the street. We are different in many ways, my wife and I, and it wont be long before shell grow weary of the restaurant grind, and then of restaurants altogether, and even for healthy lengths of time, of eating altogether. But at the beginning of this grand culinary adventure, our differences are complementary: shes petite, organized, and sensibly trim; Im large, disorganized, and prone to fits of mumbling and forgetfulness. She was raised by cheery, relentlessly well-adjusted parents on a steady American diet of Pop-Tarts, tuna salad sandwiches, and Campbells tomato soup. I come from a family of phlegmatic, generally reserved, East Coast establishment Yankees who never did much home cooking in the traditional sense of the phrase. She spent most of her childhood in the same tidy redbrick colonial house, on the same street, in a leafy tree-lined suburb of Detroit. As the child of a diplomat, I spent most of my youth wandering like a displaced, upscale gypsy, from one world capital to the next. My mother-in-law once told me that the Phillipses used to eat the same sacred rotation of blue-plate specials every day of the week out in Detroit: spaghetti with tomato sauce on Mondays; Chicken Divan smothered in cheddar cheese sauce and broccoli on Tuesdays; pork chops and applesauce on Wednesdays; and some variation of tuna casserole or beet and rice porcupine meatballs to round out the week. The Platt familys diet, however, consisted of a kind of rotating cooks tour through the countries in Asia where we lived, and we happily frittered away perhaps too much time in restaurants all over the world.