ALSO AVAILABLE

GOTHAM WRITERS' WORKSHOP

Writing Fiction

The Practical Guide from New York's

Acclaimed Creative Writing School

GOTHAM WRITERS' WORKSHOP

Fiction Gallery

Exceptional Short Stories Selected by

New York's Acclaimed Creative Writing School

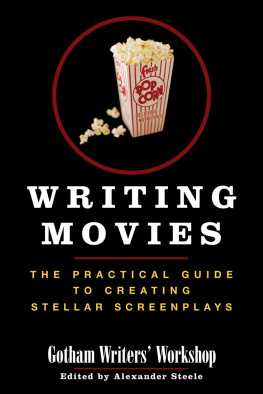

Writing Movies

The Practical Guide to Creating Stellar Screenplays

WRITTEN BY

Gotham Writers' Workshop Faculty

EDITED BY

Alexander Steele

BLOOMSBURY

Copyright 2006 by Gotham Writers' Workshop, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced

in any manner whatsoever without written permission

from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied

in critical articles or reviews. For information address

Bloomsbury, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

All papers used by Bloomsbury are natural, recyclable products

made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing

processes conform to the environmental regulations of

the country of origin.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

has been applied for.

eISBN: 978-1-59691-983-9

First U.S. Edition 2006

Typeset by Westchester Book Group

Printed in the United States of America

by Quebecor World Fairfield

You shouldn't just read your way through this book, but write your way through it as well. After all, you're reading this book because you want to write a screenplay.

In every chapter, you'll find two kinds of writing assignments. The assignments labeled Take a Shot will help you deepen your understanding of what you're learning through film analysis or by flexing your muscles with a writing exercise. The assignments labeled Stepping-Stone will give you one or more tasks designed to help you develop your own screenplay. If you have a screenplay idea you're burning to write, go ahead and use the stepping-stones on that idea. If you're not sure what you want to write about, you can just pick an idea and run with it, or you can save the stepping-stones for when you're ready. The stepping-stones are not a paint-by-numbers method for writing a great screenplay (such a thing does not exist) but they will certainly lead you in the right direction.

Throughout the book, we will be using five movies to illustrate most of our points: Die Hard, Thelma & Louise, Tootsie, Sideways, and The Shawshank Redemption. To reap the maximum benefit from this book you should watch or re-watch these movies.

You should also visit the Web site for this book: www.WritingMovies.info. There you will find the screenplays for the five movies cited above, along with other helpful material.

Contents

BY ALEXANDER STEELE

BY DANIEL NOAH

BY PAUL ZIMMERMAN

BY JOHN GLENN

BY TAL MCTHENIA

BY MICHAEL ELDRIDGE

BY HELEN KAPLAN

BY TOMMY JENKINS

BY JASON GREIFF

BY AMY FOX

BY CHRISTOPHER MOMENEE

BY ALEXANDER STEELE

In his heyday, Charlie Chaplin was the most famous person on the planet. When a certain evil dictator stormed to power in Germany in the 1930s, people asked him why he had a mustache like Chaplin's. Not the other way around. Soon the precarious state of the world was translated to movie audiences in a scene from Chaplin's The Great Dictator that showed a maniacal tyrant (played by Charlie) dancing a kind of ballet with a globe of the earth, tossing it, twirling it, finally destroying it.

Movies are the contemporary mythology. They turn our past, present, and future into lore, giving us the stories we live by.

Movies are watched by presidents and prisoners and everyone in between. No wonder their influence is so immense. When Clark Gable peeled off his shirt in It Happened One Night, revealing a bare chest, sales of undershirts plummeted. When Marlon Brando staggered about in a torn T-shirt in A Streetcar Named Desire, sales of T-shirts skyrocketed. If you don't think movies have a huge impact on our consciousness, ask anyone in the fashion industry. Their influence extends to tourism, politics, lingo, morality, even religion. From New York City to Istanbul to Kuala Lumpur.

If you're reading this, chances are you're among those who want to join the rank of modern-day Homers and write a movie. In our classes at Gotham Writers' Workshop, we've encountered thousands of people with the same worthy ambition and we've helped many of them achieve this goal. If you hope to break into the movie business, you'll need some combination of imagination, talent, skill, determination, and persistence. Maybe a little luck. Most important, you'll need to write one or more screenplays of outstanding quality. Complete screenplays. Not just ideas to be pitched in plush offices or five-page "treatments" to be developed by established screenwriters. To make it, you need complete screenplays. Of outstanding quality.

This book will help you get there. The focus of this book is on writing scripts for feature filmsmovies that run 90-120 minutes and are designed to be seen without commercial interruption. If you're more interested in writing television movies or short films, some things will be a little different, but most of the craft will be the same. The same is true for animated films, but know that scripts for animated films are almost always developed in-house by a producing organization. If you have not been hired to write your script, then you are a creating a spec screenplay, something you are writing on your own volition in the hope that someone somewhere will buy it. Spec is short for "speculation," such as "speculating in the gold market."

A Visual Medium

If God could do the tricks we do, he'd be a happy man.

Eli Cross, a megalomaniacal movie director in The Stunt Man

Film is a visual medium. That's the first thing you need to know. In prose, it's all about the words. In film, the image dominates. When you think of a movie, you see an image in your mind.

A woman swimming in moonlight jerked underwater by an unseen force. (Jaws)

A bumbling detective covering his privates with a guitar as he investigates a nudist colony. (A Shot in the Dark)

A lounge singer in a slit dress slithering across a grand piano. (The Fabulous Baker Boys)

A girl with fire-colored hair racing through streets to save her boyfriend's life. (Run Lola Run)

A twister spinning a house high above the Kansas plains. (The Wizard of Oz)

A Greek hero slashing his sword at the seven heads of a ferociously writhing hydra. (Jason and the Argonauts)

A grownup son and his father playing catch on a celestially lit baseball field. (Field of Dreams)

Go ahead, think of a favorite movie, right now. What happens?

These images can imprint themselves deeply on our psyches. A personal example. On a Saturday afternoon, when I was around five years old, I gathered around the TV with some older kids to watch a horror movie, The Tingler. (Bad idea.) I remember only one thing about that movie, but it's an image I will never shake. A deaf-mute lady was lying in bed when this evil person entered the room with the intention of harming her. Terror overtook the lady's face and although she tried to scream, she couldn't get the scream out. Now, nobody considers The Tingler a great horror movie and I might find the whole thing laughable if I watched it today, but let me tell you, that image chilled me to the core. In my mind's eye, I couldn't stop seeing that woman trying to scream! The image gave me nightmares for the better part of a year.

Reading prose fiction is largely an internal experience; we slip into the minds of the characters and envision our own pictures from the words. In film the reverse is true. We experience a movie from the outside in. We ride along with the visuals and they lead us toward our inner thoughts and sensations and emotions.

Next page

![Watt - The 90-day screenplay : [from concept to polish]](/uploads/posts/book/103527/thumbs/watt-the-90-day-screenplay-from-concept-to.jpg)