Text copyright 2010 by Condoleezza Rice

Excerpt from No Higher Honor copyright 2011 by Condoleezza Rice

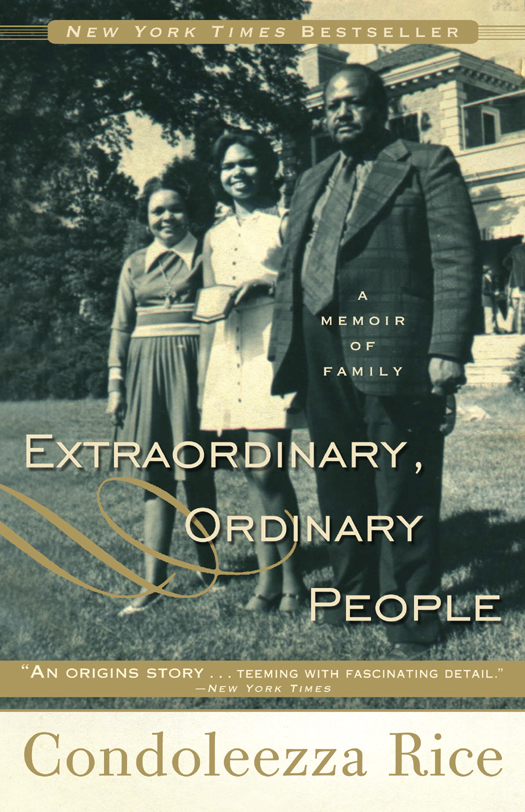

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Childrens Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. This work is based upon Extraordinary, Ordinary People: A Memoir by Condoleezza Rice, copyright 2010 by Condoleezza Rice, published in hardcover by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Permissions to come.

Visit us on the Web! www.randomhouse.com/kids and www.randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

www.randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

eISBN: 978-0-307-71960-7

Random House Childrens Books supports the

First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

To my parents,

John and Angelena Rice,

and my grandparents:

Mattie and Albert Ray,

and John and Theresa Rice

contents

A MEMOIR OF MY EXTRAORDINARY, ORDINARY FAMILY AND ME

authors note

My parents, John and Angelena Rice, were extraordinary, ordinary people. They were middle-class folks who loved God, family, and their country. They loved each other unreservedly and built a world together that wove the fibers of our lifefaith, family, community, and educationinto a seamless tapestry of high expectations and unconditional love. I dont think they ever read a book on parenting. They were just good at itnot perfect, but really good. Somehow they raised their little girl in Jim Crow Birmingham, Alabama, to believe that even if she couldnt have a hamburger at the Woolworths lunch counter, she could be president of the United States.

As it became known that I was writing a book about my parents, I received many letters and emails from people who knew my mom and dad, telling me how my parents had touched their lives. In conducting this journey into the past I also had the pleasure of returning to the places my parents lived and talking with their friends, associates, and students. I am so glad I had the chance to connect with so many who knew them.

I was also contacted by people who didnt know my parents but recognized in my story their own parents love and sacrifice. Good parents are a blessing. Mine were determined to give me a chance to live a unique and happy life. In that they succeeded, and that is why every night I begin my prayers saying, Lord, I can never thank you enough for the parents you gave me.

chapter one

By all accounts, my parents approached the time of my birth with great anticipation. My father was certain that Id be a boy and had worked out a deal with my mother: if the baby was a girl, she would name her, but a boy would be named John.

Mother started thinking about names for her daughter. She wanted a name that would be unique and musical. Looking to Italian musical terms for inspiration, she at first settled on Andantino. But realizing that it translated as moving slowly, she decided that she didnt like the implications of that name. Allegro was worse because it translated as fast, and no mother in 1954 wanted her daughter to be thought of as fast. Finally she found the musical terms con dolce and con dolcezza, meaning with sweetness. Deciding that an English speaker would never recognize the hard c, saying dolci instead of dolche, my mother doctored the term. She settled on Condoleezza.

Meanwhile, my father prepared for Johns birth. He bought a football and several other pieces of sports equipment. John was going to be an all-American running back or perhaps a linebacker.

My mother thought she felt labor pains on Friday night, November 12, and was rushed to the doctor. Dr. Plump, the black pediatrician who delivered most of the black babies in town, explained that it was probably just anxiety. He decided nonetheless to put Mother in the hospital, where she could rest comfortably.

The public hospitals were completely segregated in Birmingham, with the Negro wardsno private rooms were availablein the basement. There wasnt much effort to separate maternity cases from patients with any other kind of illness, and by all accounts the accommodations were pretty grim. As a result, mothers who could get in preferred to birth their babies at Holy Family, the Catholic hospital that segregated white and Negro patients but at least had something of a maternity floor and private rooms. Mother checked into Holy Family that night.

Nothing happened on Saturday or early Sunday morning. Dr. Plump told my father to go ahead and deliver his sermon at the eleven oclock church service. This baby isnt going to be born for quite a while, he said.

He was wrong. When my father came out of the pulpit at noon on November 14, his mother was waiting for him in the church office.

Johnny, its a girl!

Daddy was floored. A girl? he asked. How could it be a girl?

He rushed to the hospital to see the new baby. Daddy told me that the first time he saw me in the nursery, the other babies were just lying still, but I was trying to raise myself up. Now, I think its doubtful that an hours-old baby was strong enough to do this. But my father insisted this story was true. In any case, he said that his heart melted at the sight of his baby girl. From that day on he was a feministthere was nothing that his little girl couldnt do, including learning to love football.

chapter two

My parents were anxious to give me a head start in lifeperhaps a little too anxious. My first memory of confronting them and in a way declaring my independence was a conversation concerning their ill-conceived attempt to send me to first grade at the ripe age of three. My mother was teaching at Fairfield Industrial High School in Fairfield, Alabama, and the idea was to enroll me in the elementary school located on the same campus. I dont know how they talked the principal into going along, but sure enough, on the first day of school in September 1958, my mother took me by the hand and walked me into Mrs. Joness classroom.

I was terrified of the other children and of Mrs. Jones, and I refused to stay. Each day we would repeat the scene, and each day my father would have to pick me up and take me to my grandmothers house, where I would stay until the school day ended. Finally I told my mother that I didnt want to go back because the teacher wore the same skirt every morning. I am sure this was not literally true. Perhaps I somehow already understood that my mother believed in good grooming and appropriate attire. Anyway, Mother and Daddy got the point and abandoned their attempt at really early childhood education.

I now think back on that time and laugh. John and Angelena were prepared to try just about anythingor to let me try just about anythingthat could be called an educational opportunity. They were convinced that education was a kind of armor shielding me against everythingeven the deep racism in Birmingham and across America.

They were bred to those views. They were both born in the South at the height of segregation and racial prejudiceMother just outside of Birmingham, Alabama, in 1924 and Daddy in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1923. They were of the first generation of middle-class blacks to attend historically black collegesinstitutions that previously had been for the children of the black elite. And like so many of their peers, they rigorously controlled their environment to preserve their dignity and their pride.