In the modern world we produce sufficient food to feed everyone. Yet one billion people are starving. Thats one in every seven people on the planet. We produce enough but the food is not distributed in a way that ensures everyone has access to it.

Hunger is traditionally associated with Third World countries but Australia is not immune. Its not just traditionally vulnerable people, such as the homeless and unemployed, who are at risk of food insecurity but also the elderly, single parents and the working poor.

Each year two million Australians, or one in 10, seek food assistance, around half of them children.

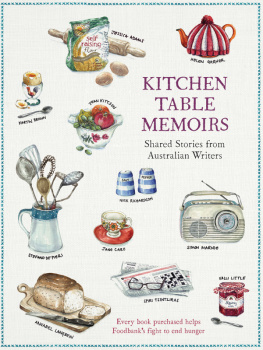

Foodbank is a non-denominational, non-profit organisation that acts as a pantry to over 2,500 charities and community groups who provide food relief to people in need.

Foodbank started in New South Wales in 1992 and is now a national organisation with distribution centres in all state capitals, the Northern Territory and 10 regional centres, including Bendigo, Dandenong, Mt Gambier, Whyalla, Riverland, Albany, Geraldton, Bunbury, Mandurah and Kalgoorlie.

In terms of volume, Foodbank is the largest hunger relief organisation in Australia, distributing 24 million kilograms of food a year. Thats the equivalent of 32 million meals a year, or 88,000 meals a day.

Despite its significant impact, Foodbank is a lean organisation run by only 90 staff nationally with the help of 3,500 volunteers.

What Foodbank does is act as a conduit between the food and grocery industrys surplus and the welfare sectors need. Over 700 companies donate unsaleable product to Foodbank. Those donations could be stock that is excess to requirement or close to date code, has incorrect labelling or damaged packaging as well as ingredients that are out of specification or surplus to need.

In addition, Foodbank partners with the countrys farmers, suppliers, manufacturers, retailers and transporters in a program to proactively source a range of staple foods such as breakfast cereals, milk, meat, fruit and vegetables, pasta and rice required to ensure the consistent provision of balanced, nutritious meals. This collaborative approach means for every $1 donation Foodbank receives, it can produce $7 worth of food.

Foodbank sorts and distributes the food to charities, community groups and schools around Australia. This food then goes to hostels, shelters, drop-in centres, school breakfast programs, home hampers and emergency relief packages for people in need.

The food and groceries Foodbank distributes annually represent a $170 million saving to the charities and community groups that Foodbank serves money which is able to be spent on other vital activities such as counselling and support to get vulnerable people back on track.

In addition, the redirected food and groceries represent a benefit in terms of environmental impact including water, land and resource savings as well as the carbon reduction associated with less product going to landfill.

Foodbank has a vision of an Australia without hunger. It believes that not knowing where your next meal is coming from is a wretched existence and one that no one in the lucky country should have to experience.

To find out more visit www.foodbank.org.au

John Webster, CEO Foodbank Australia

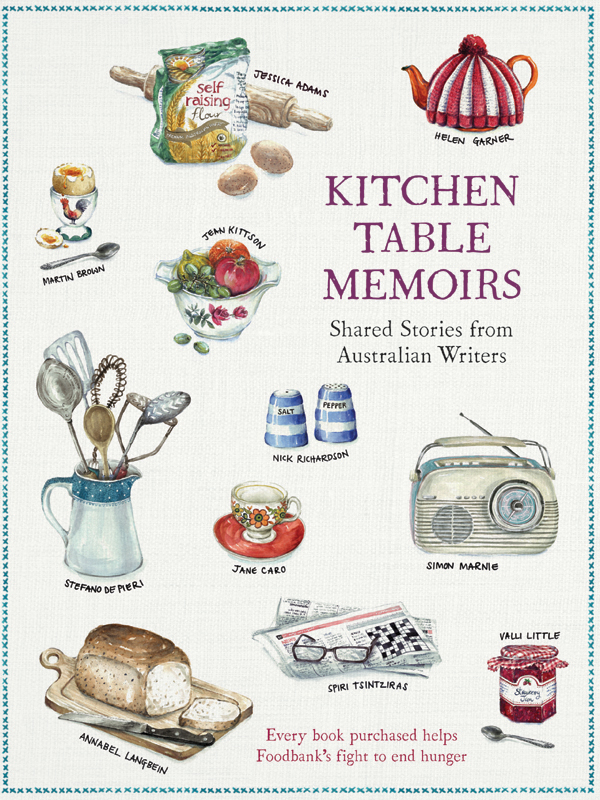

by Nick Richardson

In the domestic geography of our lives, the kitchen is a familiar country: that place where food and the family meet at different times of every day through the stages of our lives. The table is a durable physical presence that bears silent witness. We have all sat around the family table, shared food, wine, beer, arguments, triumphs, sadness and delight. Christmas might take place there. Birthdays too. Wedding and holiday plans, family conferences, small things like shelling peas from the garden, the crossword, a cup of tea or large things, like I dont think I can do this any more. Food might be the starting point for us to take a seat but there are so many other reasons why we stay at the table, long after the plates have been taken away.

My association with the kitchen table began in 1963, when my parents bought a table as part of the renovation that turned a 1930s house into a 1960s home. Or so the builder, a small, sly-mouthed man called Bowey Wise, promised my parents, in advance, before he accepted his down payment.

I cannot remember what walls were pulled down and doorways sealed up. That was for my older brothers, both of whom recall the picture of the domestic landscape before The Alterations. But I remember the tables ceaseless presence from then on. It outlasted my father, who used the table as the key prop in his simple domestic routine. It survived our mad Labrador who hid underneath it on the cool lino when the heat outside started to crackle and she dived inside to escape. And it endured countless family dramas, some that became arguments, and many others that were brought to a premature close by a clatter of plates, knives and forks being picked up and dunked in the sink.

My father used the table like a command post, swivelling between the back window that looked out over the double block of garden he cultivated every weekend, to his place at the head of the table. That was his post, poised for his evening meal, like a boarding-school boy, waiting for the plate to appear before him. Even now, in the catalogue of family photos, there is a stash of him, bent over the table, writing Christmas cards, reading the race form, pouring a beer into a seven-ounce glass he kept in the fridge.

This landscape of beer, cigarettes and subtle authority was, even then, a strange thing to contemplate: how was it that the table was supposedly for all of us yet seemed to be so obviously about only one of us? My father had colonised it by stealth. We felt like interlopers when we tried to join him without the passport offered by a meal. It was a place where Dad commanded; it was left unguarded only after school, when he was still at work, or for some of the weekends, when he was in the back yard. The table had a compelling conspiracy with my father. Not that Dad actually wanted it all to himself. He enjoyed the company of others, but it was as though he and the table shared an understanding: it was like a loyal hound, with only one master. Was it any wonder I felt suspicious of the table?

If this was not challenging enough, there was also an ever-present danger. My mother understood this instinctively. Her hands would rush to cover the tables sharp, shiny corners every time a small person went near. She was especially vigilant when my cousin Yasmin only three months older than me would come over for lunch. The two of us shared a kaleidoscope of fork-stirred vegetables potatoes, carrots, parsnip and swede overcooked, mashed and threaded with Vegemite as the singular enticement. But Yasmin, with what seems now to be a peculiar lack of comradeship, was not the most diligent eater. At the prime vegetable-hating age of five, Yasmin and I hid under the table when the bowls of vegetables were waiting for us. I gazed up at the shafts of wood that housed the table wings and the chrome supports that strengthened the legs firm hold on the house. And then I slid out, just to make sure my mother was not around. At that moment, Yasmin pushed me, quickly and firmly and without malice. I have no recollection of what happened next, other than somehow part of my head struck the firm sharp corner of the table. I had a sensation of rich red globes of blood pulsing from my eyebrow, and my mother urgent, efficient and working hard to remain calm using what appeared to be the corner of a white sheet to stem the bleeding. And I glanced at my cousin, who seemed quiet, reserved, staring, saying nothing, watching the blood.